From Tammy to Tamagotchi: How Toys Reflect the Psychology of Childhood

Maria Fonseca

Tue Jul 15 2025

This article explores how iconic toys—from Tammy dolls to Tamagotchis—reflect the evolving psychology of childhood across generations. Drawing on Hamleys’ 2025 list of the top 100 toys of all time, it connects key toys to developmental milestones like identity formation, emotional regulation, and imaginative play. The piece highlights how toys serve as cultural mirrors and emotional tools for children navigating a changing world. It ultimately celebrates the enduring power of play as essential to growth, creativity, and connection.

Toys are more than mere entertainment; they are windows into the soul of childhood. They mirror our hopes, fears, and developmental needs—miniature tools through which children explore identity, emotions, creativity, and the world around them. In July 2025, Hamleys—the world’s oldest toy store—released its definitive list of the 100 greatest toys of all time, a collection spanning over 260 years of play. From humble spinning tops to Tamagotchis and Game Boys, these toys tell a story not just of nostalgia, but of how play has evolved alongside our understanding of childhood psychology.

The Psychology of Play: Why Toys Matter

According to developmental psychologists like Jean Piaget and Erik Erikson, play is essential to cognitive, emotional, and social growth. A toy is a child's first “job,” the arena in which they experiment with autonomy, belonging, control, and creativity. Whether stacking blocks or raising a virtual pet, children are shaping their inner lives through outer objects.

Toys help children:

Build motor skills (e.g. Slinky, Yo-Yo)

Develop social roles and narratives (e.g. Barbie, Action Man)

Learn problem-solving and logic (e.g. Rubik’s Cube)

Express care and empathy (e.g. Tiny Tears, Tamagotchi)

Understand risk and consequence (e.g. Operation, KerPlunk)

With that framework in mind, let’s explore how toys across the decades reflect evolving ideas of childhood.

Early Toys: Simplicity, Rhythm, and Imagination

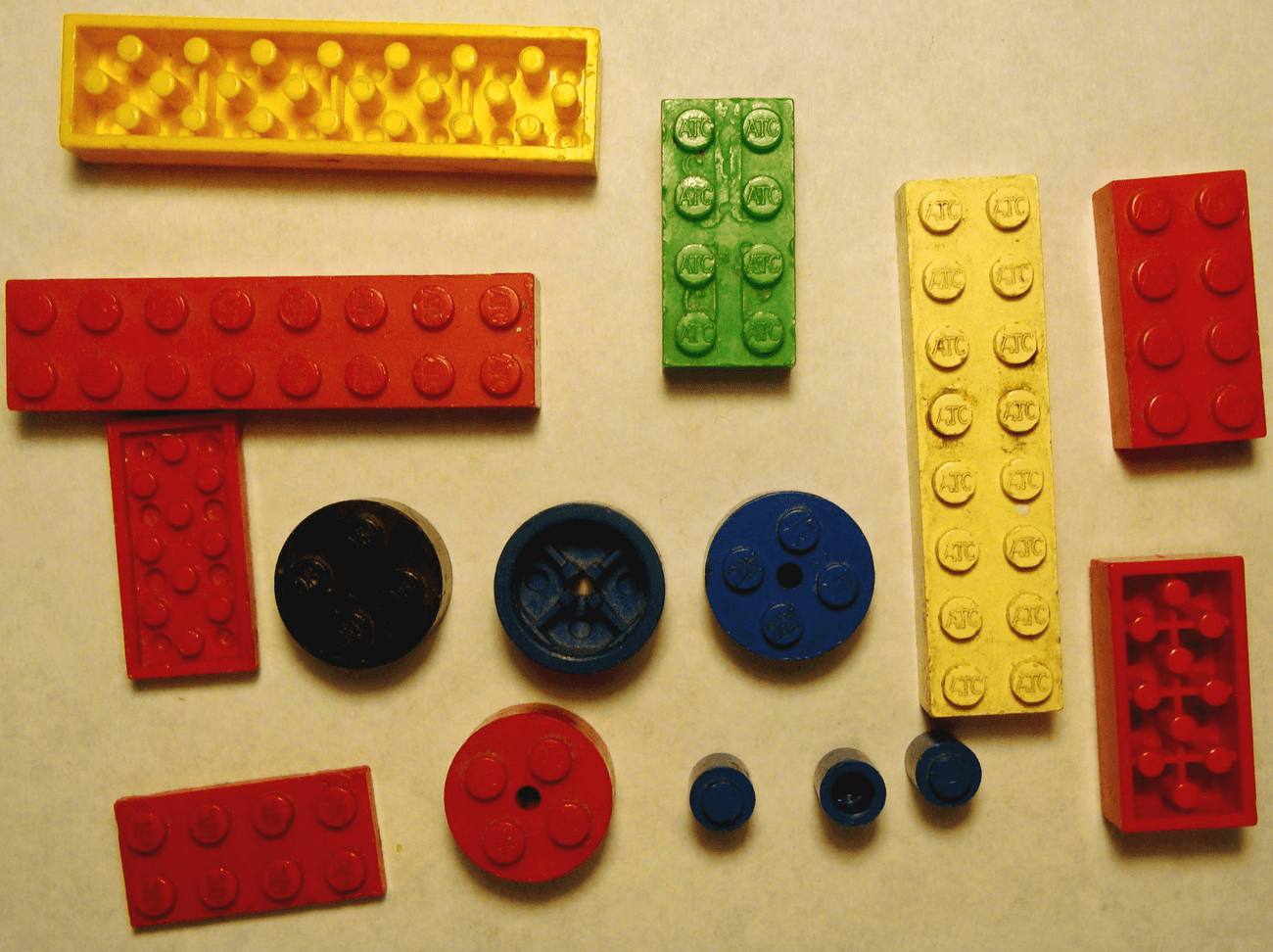

Many toys on Hamleys’ list predate the plastic age. Marbles, hula hoops, spinning tops, and rocking horses represent the earliest traditions of toy-making—simple, rhythmic, sensory experiences that build coordination and joy.

These toys reflect sensorimotor development, as described by Piaget. Children between birth and age 2 explore the world through touch, movement, and manipulation. The repetition of rolling a hoop or bouncing a yo-yo gives children a sense of control over their environment—a foundation for later confidence.

Their timeless appeal lies in their open-endedness. A spinning top doesn't tell a story, but it invites one.

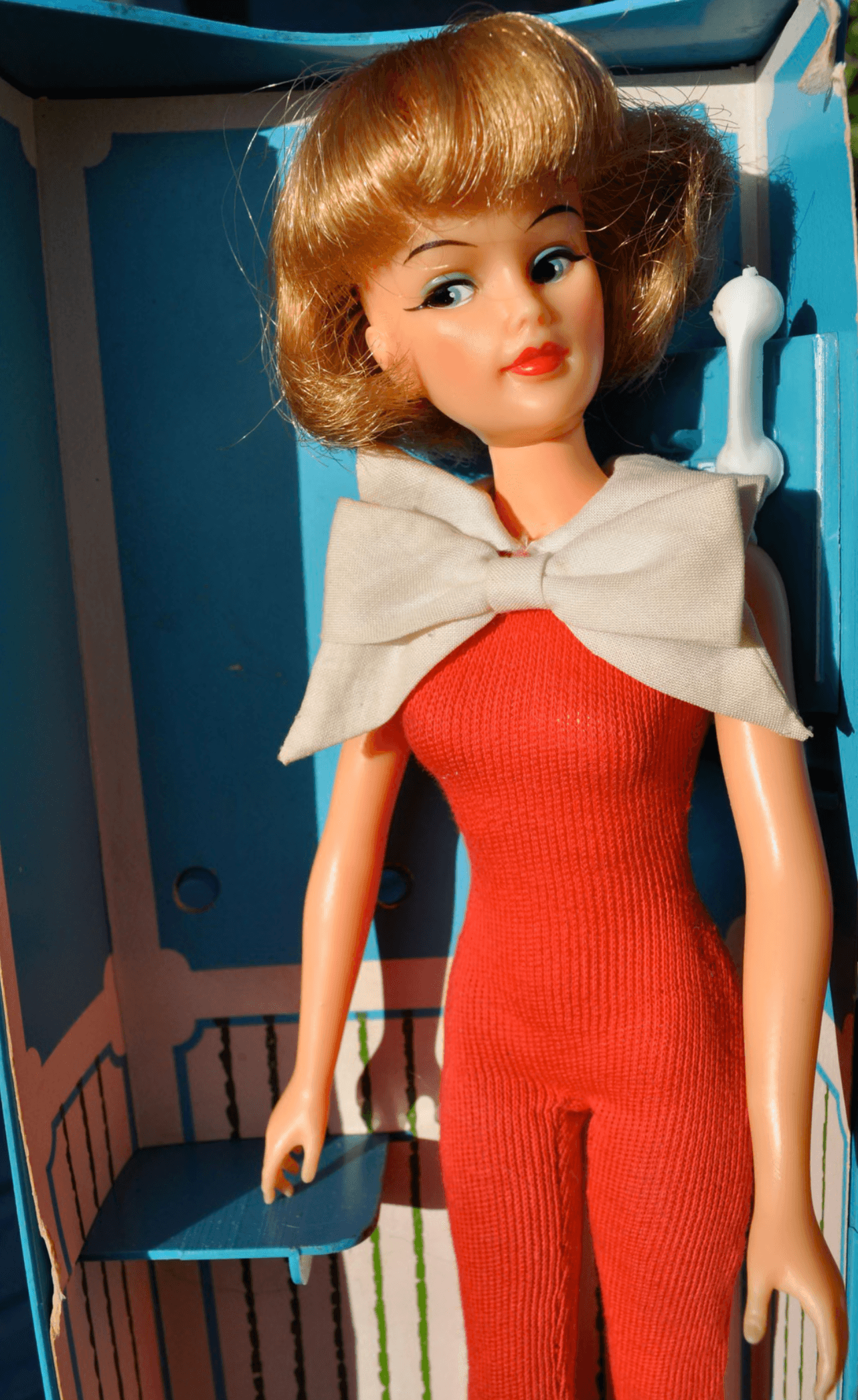

Mid-Century Identity Toys: Dolls, Figures, and the Emergence of Self

By the 1950s and 60s, toys began to reflect post-war shifts in gender roles, media, and domestic ideals. Tammy, released in the early 1960s, was seen as a more wholesome alternative to Barbie—a “girl next door” who emphasized friendliness over fashion. Though she faded in popularity, her mention in the Hamleys list highlights how toys become cultural mirrors for idealized versions of childhood.

Barbie (1959) and Action Man (1966) soon dominated shelves. These dolls allowed children to experiment with adult roles—from astronaut to fashion designer—well before they had the language to describe who they were. Erikson’s theory of identity development sees this as essential: in the stages of initiative vs. guilt and industry vs. inferiority, play with figures helps children internalize social norms and imagine future selves.

Tiny Tears, Cabbage Patch Kids, and Polly Pocket expanded the emotional landscape. Children could now explore nurturing and attachment, themes drawn from Bowlby’s attachment theory. Carrying a doll, feeding it, changing its clothes—these acts echo the caregiving children themselves receive and mimic.

The Puzzle Boom: Mastery, Logic, and the Joy of Frustration

The 1970s and 80s brought toys that challenged the mind. Rubik’s Cube—possibly the most iconic of all time—epitomized a new kind of play: logic, patience, and pattern recognition. It sold over 500 million units and remains a cultural icon of perseverance.

Electronic toys like Simon and Speak & Spell took this a step further, blending audio-visual stimulation with memory training. These reflected growing educational aspirations in Western societies—part of a shift toward “edutainment”, where play meets performance.

Psychologically, these toys satisfy a deep desire for mastery. According to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s concept of flow, children enter peak states of concentration when challenged just enough—exactly what puzzle toys like Jenga, Connect 4, and Operation provide. They also teach children how to handle frustration, a vital emotional skill for navigating life.

The Digital Turn: Tamagotchi and the Rise of Virtual Emotion

Few toys better embody 1990s childhood than the Tamagotchi. Released in 1996, this tiny egg-shaped virtual pet needed regular feeding, cleaning, and affection—or it would “die.” At the time, many schools banned it, worried about classroom distraction. But psychologists were intrigued.

Here was a toy that taught responsibility, care, and consequence. It mirrored real attachment: the pet became a kind of companion, not unlike a transitional object or comfort blanket. The Tamagotchi also revealed a new psychological relationship emerging in the digital age: empathy toward virtual beings.

This foreshadowed today’s debates about artificial intelligence and child-robot interaction. If a 7-year-old can feel heartbreak over a dying Tamagotchi, what happens when AI companions become more lifelike?

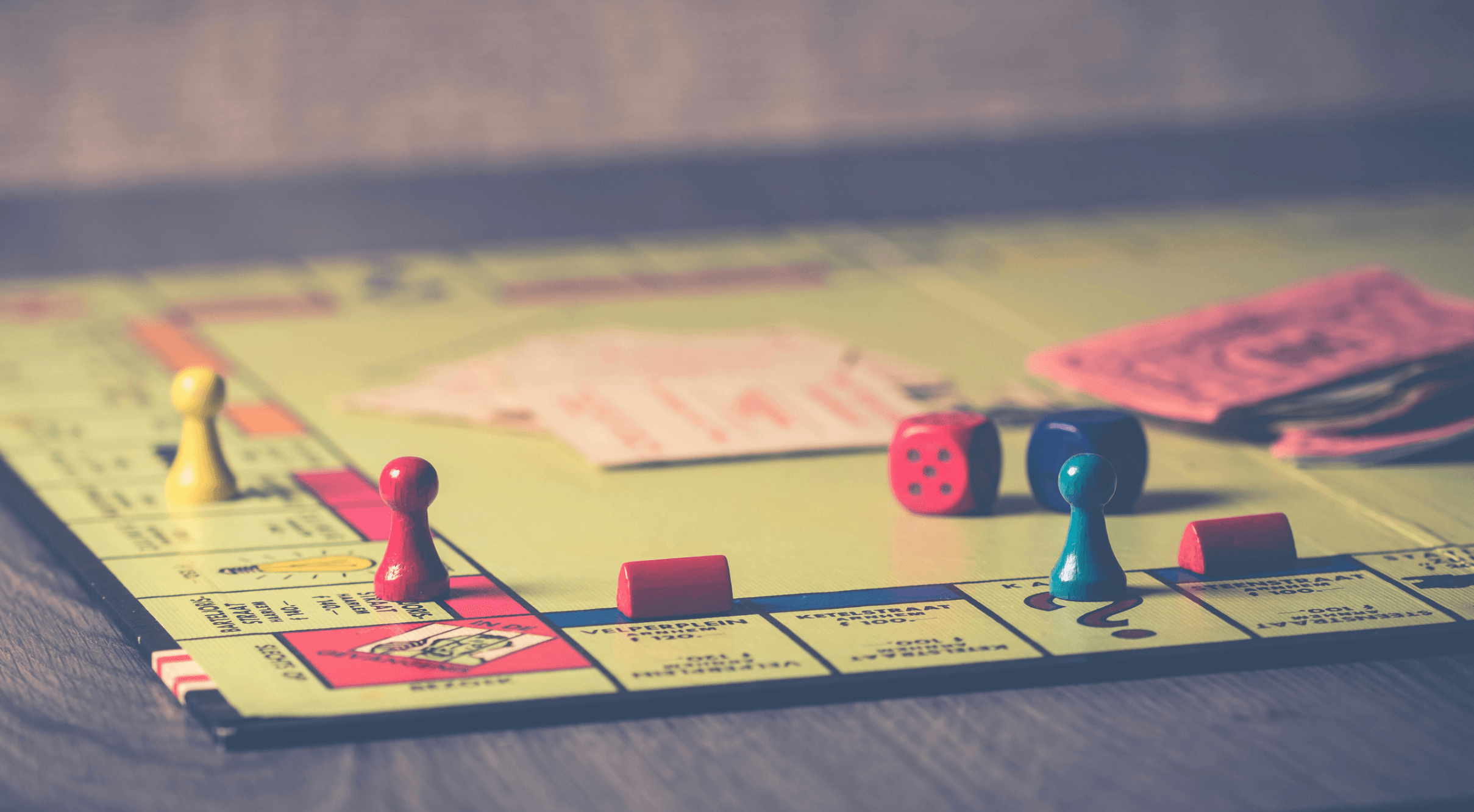

Family Games and Risk: Learning Through Jeopardy

Board games like Monopoly, KerPlunk, Operation, and Buckaroo remain ever-present in Hamleys’ list. These are not just fun—they teach turn-taking, cooperation, rule-following, and crucially, emotional regulation.

Risk-based games, where a wrong move causes a tower to tumble or a buzzer to shriek, allow children to confront anticipation and loss in low-stakes environments. These experiences mirror life: sometimes you win, sometimes you wobble.

Group games also support bonding and attachment across generations. Grandparents and grandchildren can meet on a level playing field. The laughter and suspense of shared play form what psychologist Donald Winnicott called a “holding environment”—a space where the child feels safe to take risks.

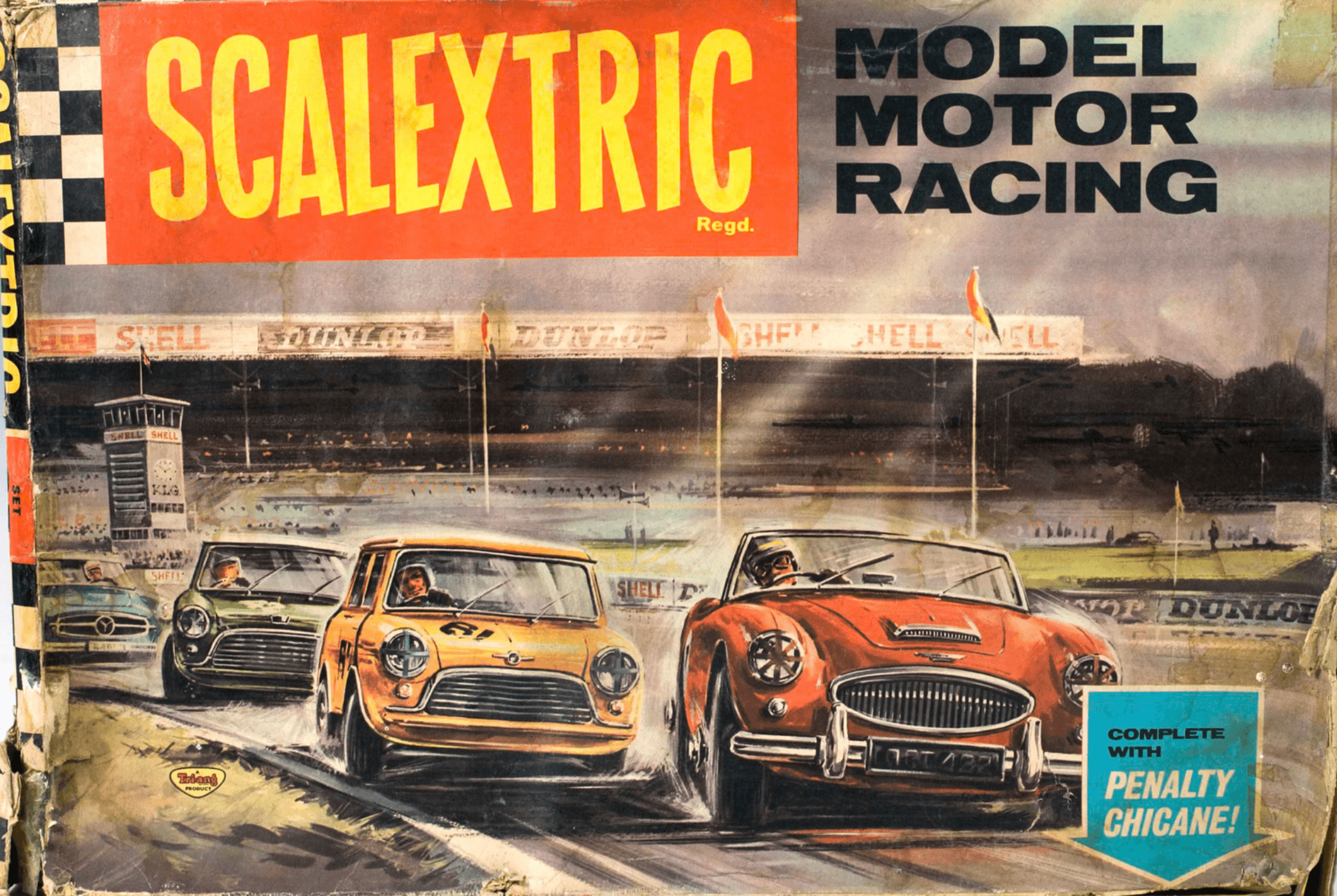

Pop Culture and Identity: The Toys We Saw on TV

From Star Wars figures to Transformers, Thunderbirds’ Tracy Island to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, the Hamleys list underscores the growing symbiosis between toys and mass media. Children no longer just invented stories—they played them out from TV and film.

This has complex psychological effects. On one hand, familiar characters give children comfort and shared culture. On the other, branded toys can limit imaginative scope. A block can become anything; Optimus Prime is always Optimus Prime.

Nonetheless, the emotional resonance of these characters allows children to project and process feelings—anger, bravery, fear, rebellion—through play. Whether battling the Empire or exploring the sewers with Leonardo, children rehearse emotional themes safely.

The Present: Digital Hybrids and Open-Ended Play

In recent years, toys like Nintendo Switch, LEGO Boost, and interactive plush toys combine physical play with digital feedback. Augmented reality is entering the toybox. But classic toys—like Play-Doh, Slinky, and Lego—remain. Why?

The best toys, as Hamleys’ curator Victoria Kay notes, are those that are emotionally rewarding, open-ended, and socially engaging. A toy doesn’t need to be high-tech to be effective—it needs to resonate with how children grow.

The modern child must navigate a more complex world—screen time, environmental awareness, gender fluidity, and early mental health awareness. Toys now reflect this: more inclusive dolls, eco-conscious craft kits, and games that focus on feelings and wellbeing.

Toys as Time Capsules of the Inner Child

Looking back through Hamleys’ list, one thing becomes clear: toys are cultural artefacts, but also psychological tools. They allow children to symbolically confront, shape, and celebrate their world. Whether caring for Tammy, solving a Rubik’s Cube, or grieving a lost Tamagotchi, children are engaged in serious inner work—through joyful, often noisy, seemingly chaotic play.

In a time when childhood is increasingly structured and pressured, toys remind us of the value of freedom, exploration, and the wisdom of play. Every generation has its icons—but the impulse behind them remains the same: to imagine, to connect, and to become.

References:

Hamleys Top 100 Toys of All Time, July 2025. As reported by The Guardian, ITV, and Inkl.

Piaget, J. The Psychology of Intelligence (1950).

Erikson, E. H. Childhood and Society (1950).

Csikszentmihalyi, M. Flow (1990).

Winnicott, D. W. Playing and Reality (1971).

previous

Who Were the Normans? The Fierce Descendants of Vikings Who Shaped Europe Today

next

Elder Voices of the Millennium: Vandana Shiva — The Seed of Wisdom

Share this

Maria Fonseca

Maria Fonseca is an interdisciplinary educator, writer, artist and researcher whose work bridges the realms of academic knowledge, community engagement, and spiritual inquiry. With a background in Fine Art and a doctorate in creative practice, Maria has spent over a decade exploring the intersections of human experience, cultural meaning, and collective transformation.

More Articles

Fei-Fei Li – World-Building: Human Centric AI

The Science and Soul of Smiling: Why Your Face Holds the Power to Transform Your Life

The Switz Birds: Where Chaos Meets Curiosity

How AI Is Rewiring the Learning Brain: The Hidden Costs of Cognitive Convenience

The Creative Contract Between Humans and Earth: Restoring Reciprocity with the Living World