The Cinematic Titans: 100 Filmmakers Who Taught Humanity to Dream in Motion

Dinis GuardaAuthor

Thu Nov 20 2025

Explore 100 cinematic masters who shaped film history, from Lumière Brothers to Christopher Nolan. From the whitepaper by Dinis Guarda on humanity's greatest creators

From the whitepaper "Top 400 Most Influential Creators Artists of All Time" by Dinis Guarda

Each human being is humanity. — Dinis Guarda

When Light Became Dreams: The Birth of Cinema

Cinema is our youngest art form, barely 130 years old. Yet it has become our most powerful, combining every art that came before. It takes painting's visual composition, music's emotional rhythm, literature's narrative structure, theatre's performance, and architecture's sense of space. Then it adds motion, light, and time itself.

These 100 filmmakers didn't just make movies. They taught us new ways to see, feel, and understand what it means to be human.

Silent Era Pioneers (1895-1930): When Dreams Learned to Move

Auguste and Louis Lumière invented cinema itself in 1895, screening flickering life in a Parisian café. Georges Méliès, magician-turned-filmmaker, created A Trip to the Moon (1902) and invented special effects, showing us that cameras could lie beautifully.

D.W. Griffith innovated film language while creating racist epics. Charlie Chaplin gave us The Tramp, humanity's most universal character, speaking volumes through silence in City Lights and Modern Times. Buster Keaton, stone-faced and fearless, performed impossible stunts in The General.

Sergei Eisenstein theorized Soviet montage in Battleship Potemkin and October, revolutionizing how we understand editing. Dziga Vertov made Man with a Movie Camera, pure visual poetry documenting Soviet life.

The Europeans brought darkness: F.W. Murnau's Nosferatu and Sunrise, Fritz Lang's Metropolis (1927) and M (1931), Erich von Stroheim's Greed, Hollywood's first auteur martyr who fought the studio system and lost.

Golden Age Hollywood (1930-1960): The Dream Factory's Masters

John Ford won four Oscars filming the American West (The Searchers, Stagecoach). Howard Hawks mastered every genre from screwball (His Girl Friday) to noir (The Big Sleep) to westerns (Rio Bravo).

Frank Capra, the Sicilian immigrant, made populist dreams (It's a Wonderful Life, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington). Alfred Hitchcock, the Master of Suspense, made fear an art form—Psycho, Vertigo, Rear Window remain blueprints for terror.

Billy Wilder wrote and directed cynicism with heart (Sunset Boulevard, Some Like It Hot). Orson Welles created Citizen Kane at 25, revolutionizing cinema overnight, then spent 44 years trying to match it.

Elia Kazan directed actors to transcendence (On the Waterfront, East of Eden) before naming names to HUAC, forever staining his legacy. William Wyler, the perfectionist, gave us Ben-Hur and The Best Years of Our Lives. George Stevens made Shane and Giant, and filmed WWII concentration camps as a military documentarian.

Otto Preminger challenged censorship with The Man with the Golden Arm, pushing Hollywood's boundaries.

International Masters (1930-1960): When the World Found Its Voice

Jean Renoir, the painter's son, brought humanist poetry to Grand Illusion and Rules of the Game. Marcel Carné created poetic realism in Children of Paradise, one of cinema's greatest achievements.

Italy's Vittorio De Sica filmed poverty with dignity in Bicycle Thieves (1948), using non-actors with reverence. Roberto Rossellini documented war's aftermath in Rome, Open City (1945), neorealism's foundation. Luchino Visconti, an aristocratic Marxist, captured Italian transformation in The Leopard (1963).

Japan's Yasujirō Ozu never moved his camera, filming families with Zen minimalism (Tokyo Story, 1953). Kenji Mizoguchi pioneered feminist cinema before feminism existed (Ugetsu, 1953), mastering the long take. Akira Kurosawa, cinema's samurai philosopher, made Seven Samurai (1954), Rashomon (1950), Ran (1985). After Hollywood rejected him, he attempted suicide, then returned to create masterpieces into his 80s.

Satyajit Ray's Apu Trilogy put Indian cinema on the world map, bringing humanist cinema to Calcutta. Ingmar Bergman made God's silence visible in Swedish existentialism (The Seventh Seal, Persona, Fanny and Alexander), filming the soul's interior.

New Waves & Revolutions (1960-1980): When Cinema Broke Itself Open

Federico Fellini made "Felliniesque" an adjective with dreamscape architecture (La Dolce Vita, 8½). Michelangelo Antonioni filmed alienation, making silence speak volumes (L'Avventura, Blow-Up). Pier Paolo Pasolini, Marxist poet-filmmaker, created The Gospel According to St. Matthew before being mysteriously murdered on a beach. Bernardo Bertolucci crafted operatic epics (The Conformist, Last Tango in Paris, The Last Emperor).

Jean-Luc Godard broke every rule with Breathless (1960), made 150+ films, quoted constantly, understood rarely. He died by assisted suicide at 91. François Truffaut became cinema's romantic with The 400 Blows and Jules and Jim, the critic who became an auteur. Alain Resnais mapped memory itself in Hiroshima Mon Amour and Last Year at Marienbad. Agnès Varda, the French New Wave's "grandmother," made feminist documentaries (Cléo from 5 to 7) that redefined the form.

Luis Buñuel, the Spanish surrealist, slit eyeballs in Un Chien Andalou (1929), then made the bourgeoisie squirm for 50 years. Andrei Tarkovsky made time visible in Russian mysticism (Solaris, Stalker, The Mirror), dying of lung cancer in exile, a martyr to his art.

Krzysztof Kieślowski philosophized through film (Dekalog, Three Colors trilogy), retiring after Red and dying shortly after, Poland's moral philosopher. Stanley Kubrick, perfectionist recluse who made 13 films over 46 years, each a genre's apotheosis. 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) remains cinema's greatest achievement. The Shining, Dr. Strangelove, Full Metal Jacket follow closely. Died days after completing Eyes Wide Shut.

Sidney Lumet chronicled New York with urgent humanism (12 Angry Men, Dog Day Afternoon, Network). Sam Peckinpah,"Bloody Sam", made violence balletic in The Wild Bunch (1969), slow-motion brutality as poetry. Robert Altman, the iconoclast, captured American chaos through overlapping dialogue (Nashville, McCabe & Mrs. Miller). Arthur Penn made violence sexy and death sudden in Bonnie and Clyde (1967).

Mike Nichols, the Berlin-born theatre director, conquered cinema with The Graduate and Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, bringing theatrical intensity to film. Roman Polanski, survivor of Kraków ghetto, Holocaust, Manson murders. Made Chinatown (1974) and The Pianist (2002). Convicted rapist in exile. Genius and monster coexist.

Terrence Malick, reclusive philosopher-poet, makes light transcendent (Days of Heaven, The Tree of Life), films as prayers. Werner Herzog, German madman, hauled a steamship over a mountain (Fitzcarraldo), hypnotized actors, ate his shoe on a bet, documents humanity's extremes.

Blockbuster Auteurs & New Hollywood (1970-1990): When Art Met Commerce

Francis Ford Coppola created The Godfather trilogy and Apocalypse Now, went bankrupt making One from the Heart, now owns wineries. At 85, he released Megalopolis (2024), a self-financed passion project defying Hollywood.

Martin Scorsese, at 82, remains cinema's greatest living practitioner, Catholic guilt transformed into Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Goodfellas, The Irishman. Still working, still obsessed with cinema's history and future.

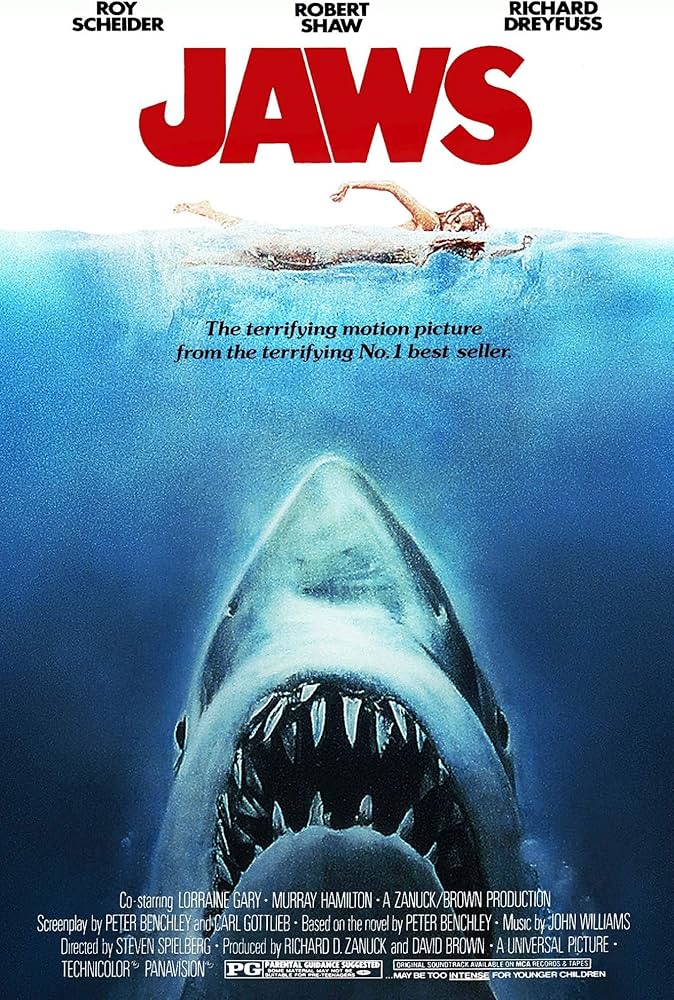

Steven Spielberg gave us Jaws, E.T., Schindler's List, Saving Private Ryan. Made blockbusters respectable, sentiment powerful. At 78, cinema's most successful storyteller, populist genius who never condescends.

.jpg?mode=max)

George Lucas created Star Wars (1977) and Indiana Jones, changed cinema's economics forever. Sold Lucasfilm to Disney for $4 billion, now focused on philanthropy and education.

Brian De Palma inherited Hitchcock's playbook, mastering split-screen and voyeurism (Carrie, Blow Out, Scarface). William Friedkin made The French Connection and The Exorcist, New Hollywood's wild man who brought documentary grit to genre films.

Peter Bogdanovich, the film scholar-director, made The Last Picture Show while romancing Cybill Shepherd, Hollywood's last classicist. Hal Ashby, counter-culture's poet, gave us Harold and Maude, Being There, and Coming Home, gentle subversion in chaotic times.

John Cassavetes, independent cinema's godfather and actor-director, self-financed raw emotional excavations (Faces, A Woman Under the Influence), proof that personal filmmaking could survive Hollywood's margins.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder, German New Wave workaholic, made 40+ films in 13 years before dying of a drug overdose at 37, a comet burning too bright.

Asian Masters (1950-2000): Eastern Philosophy Meets Western Form

Wong Kar-wai makes longing visible through Christopher Doyle's cinematography (In the Mood for Love, Chungking Express), Hong Kong aesthete of desire and memory. Taiwan's Hou Hsiao-hsien masters long takes and historical memory (A City of Sadness), while Edward Yang created epic city symphonies (Yi Yi, 2000), few films but each essential.

Korea's Kim Ki-duk explored human cruelty through silent violence before dying of COVID-19 complications in 2020. Park Chan-wook architected the baroque vengeance trilogy (Oldboy, 2003). Bong Joon-ho made Parasite (2019), the first non-English Best Picture Oscar winner, a genre-bending social critic conquering Hollywood.

Hayao Miyazaki, animation god at 83, makes hand-drawn dreams (Spirited Away, Princess Mononoke). Retires and un-retires repeatedly; released The Boy and the Heron (2023). His Studio Ghibli partner Isao Takahata made Grave of the Fireflies, cinema's saddest film. Satoshi Kon created dream logic (Perfect Blue, Paprika) influencing Black Swan and Inception before pancreatic cancer killed him at 46.

China's Zhang Yimou (Raise the Red Lantern, Hero) became Fifth Generation's ambassador, later directing Beijing Olympics ceremony, art meeting propaganda.

Contemporary American Masters (1980-2010): The New Prophets

Spike Lee remains Brooklyn's chronicler and Black cinema's conscience (Do the Right Thing, 1989). At 67, still angry, still essential, still forcing America to confront itself.

David Lynch makes nightmares beautiful (Blue Velvet, Mulholland Drive, Twin Peaks) while painting and promoting Transcendental Meditation, surrealist who never compromised. Tim Burton's gothic aesthetic conquered Halloween (Edward Scissorhands, Ed Wood), Hot Topic's patron saint.

Quentin Tarantino, video-store clerk turned postmodern prophet (Pulp Fiction, Kill Bill), plans to retire after his tenth film (currently at nine), cinema's greatest magpie.

Paul Thomas Anderson, at 54, is his generation's finest craftsman (There Will Be Blood, Phantom Thread, Licorice Pizza), American epic-maker with operatic ambitions. Wes Anderson makes dollhouse cinema where symmetry is ideology (The Grand Budapest Hotel, Moonrise Kingdom), aesthete as auteur.

The Coen Brothers, Joel and Ethan, make nihilism funny (Fargo, No Country for Old Men, The Big Lebowski). Sibling visionaries who share a brain. David Fincher shoots 100 takes perfecting darkness (Fight Club, The Social Network, Gone Girl), perfectionist technician who makes control art.

Christopher Nolan makes complexity commercial (Interstellar, Inception, The Dark Knight, Oppenheimer), blockbuster intellectual, Oscar winner at 53 proving smart cinema sells. Denis Villeneuve, French-Canadian who conquered Hollywood (Arrival, Blade Runner 2049, Dune), proves intelligent sci-fi can be popular and profitable.

European Contemporaries (1980-Present): Continental Provocateurs

Denmark's Lars von Trier makes beautiful cruelty (Breaking the Waves, Melancholia), once declared himself "Nazi" at Cannes as a joke, got banned. Provocation as methodology. Austria's Michael Haneke punishes viewers and characters equally (Funny Games, The White Ribbon, Amour), the sadist as moralist.

Spain's Pedro Almodóvar makes transgression tender (All About My Mother, Talk to Her), melodramatist who turned melodrama respectable. Belgium's Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne create handheld social realism (Rosetta, The Kid with a Bike), brothers filming working-class life with urgency.

Hungary's Béla Tarr made Sátántangó, seven hours of black-and-white apocalypse, glacial long takes that test endurance and reward patience. Turkey's Nuri Bilge Ceylan is the Turkish Chekhov whose Winter Sleep (2014) won the Palme d'Or.

Italy's Paolo Sorrentino is Fellini's baroque heir (The Great Beauty, Youth), operatic stylist of Italian decadence. Greece's Yorgos Lanthimos makes deadpan dystopias (Dogtooth, The Favourite, Poor Things), absurdist whose weird feels prophetic.

Masters of Genre: When Commerce Becomes Art

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/htra147_vv262-2000-cc0d2d34526247b6bdd76a6d15957111.jpg)

John Carpenter composes his own synth scores for horror-sci-fi auteur works (Halloween, The Thing), DIY genius. Canada's David Cronenberg, the "Baron of Blood," philosophizes through body horror (The Fly, Videodrome, Crash), making flesh think.

George A. Romero made zombies metaphors (Night of the Living Dead, 1968), the dead rising as social commentary. Italy's Dario Argento created operatic giallo (Suspiria, 1977), color-saturated horror as art form.

Mexico's Guillermo del Toro humanizes monsters (Pan's Labyrinth, The Shape of Water), collector of curiosities who makes outsiders heroes. James Cameron advances technology through blockbusters (The Terminator, Aliens, Titanic, Avatar), technical pioneer who makes spectacle meaningful.

Contemporary Visionaries: The Future Is Now

Mexico's Alejandro González Iñárritu makes long takes transcendent (Birdman, The Revenant), Mexican fabulist conquering Hollywood. Alfonso Cuarón brings virtuosic camera choreography (Gravity, Roma), technical excellence serving emotional truth.

America's Barry Jenkins writes poetry of Black masculinity (Moonlight, If Beale Street Could Talk), tender when cinema demands toughness. Ari Aster makes familial dread (Hereditary, Midsommar), horror auteur where family is the monster.

Greta Gerwig, actress-turned-director, made Lady Bird and Barbie, the latter earning $1.4 billion from a Mattel toy, proving feminist filmmaking prints money. New Zealand's Jane Campion (The Piano, The Power of the Dog) became the second woman to win Palme d'Or, the first to win twice, pioneer still pioneering.

The Impossibility Made Manifest

This list is a lie, not because it's inaccurate, but because ranking revelations is fundamentally impossible. How do you compare Chaplin's silence to Godard's chaos? Kurosawa's samurai to Hitchcock's suspense? Ozu's stillness to Scorsese's violence?

You can't. And that's precisely the point.

What this compendium reveals is not hierarchy but constellation, 100 stars in cinema's firmament, each burning with its own frequency, each necessary to the whole. Remove one and the universe dims.

These aren't monuments, they're mirrors, invitations, permission slips.

Every time you frame a photo, Kubrick whispers. Every time you tell a story, Truffaut guides you. Every time you watch the light change, Malick walks beside you. Every time you make someone laugh, Chaplin smiles. Every time you cut between two images, Eisenstein nods.

You are the 101st filmmaker.

The camera's eye opens. The frame awaits. The impossible becomes possible the moment you begin.

What will you add to humanity's mirror?

The Complete Journey: 400 Souls Who Forged Humanity's Mirror

This concludes our exploration of the 400 most influential creators of all time:

- The Visual Alchemists: 100 Artists Who Transformed How Humanity Sees

- The Sound Sculptors: 100 Musicians Who Transformed How Humanity Hears

- The Multidisciplinary Titans: 100 Artists Who Transcended Medium

- 100 Cinematic Titans: From the Lumière brothers to Greta Gerwig, filmmakers who taught us to dream in motion

Together, these 400 souls prove one unshakeable truth: Each human being IS humanity.

When they created, all of humanity created. When they dreamed, all of humanity dreamed. When they dared to make the invisible visible, the inaudible audible, the impossible manifest, they gave us permission to do the same.

The infinite canvas of human possibility stretches before you.

What will you create before death claims its due?

Compiled from 47 academic texts, 23 institutional databases, 15 critical surveys, 8 biographical encyclopedias and 5,000 years of human civilization attempting to understand why we must create or die.

previous

From Lab to Life: How Leading Universities Are Redefining Neurodiversity and Disability Through AI Research

next

When Profit Meets Purpose: How Microsoft and Corporate Leaders Are Proving the Business Case for Accessibility

Share this

Dinis Guarda

Author

Dinis Guarda is an author, entrepreneur, founder CEO of ztudium, Businessabc, citiesabc.com and Wisdomia.ai. Dinis is an AI leader, researcher and creator who has been building proprietary solutions based on technologies like digital twins, 3D, spatial computing, AR/VR/MR. Dinis is also an author of multiple books, including "4IR AI Blockchain Fintech IoT Reinventing a Nation" and others. Dinis has been collaborating with the likes of UN / UNITAR, UNESCO, European Space Agency, IBM, Siemens, Mastercard, and governments like USAID, and Malaysia Government to mention a few. He has been a guest lecturer at business schools such as Copenhagen Business School. Dinis is ranked as one of the most influential people and thought leaders in Thinkers360 / Rise Global’s The Artificial Intelligence Power 100, Top 10 Thought leaders in AI, smart cities, metaverse, blockchain, fintech.