The Psychology of an Overthinker: Understanding the Cycle

Hind MoutaoikiIR&D Manager

Fri Apr 18 2025

Overthinking represents one of the most common yet misunderstood psychological patterns of our age. Far from a mere personality quirk, overthinking reflects complex neurological processes that merit deeper understanding, particularly as we navigate an increasingly information-dense world.

In the quiet hours of the night, when the world slows its relentless pace, the mind of an overthinker accelerates. Thoughts cascade like dominoes, each triggering the next in an endless procession that defies sleep and peace alike. This phenomenon—overthinking—represents one of the most common yet misunderstood psychological patterns of our age. Far from a mere personality quirk, overthinking reflects complex neurological processes that merit deeper understanding, particularly as we navigate an increasingly information-dense world.

The Anatomy of Overthinking

At its core, overthinking involves recursive thought patterns—mental loops that revisit the same terrain without reaching resolution. Neuroscientists at King's College London have identified distinctive activity patterns in the default mode network (DMN)—a constellation of brain regions that becomes particularly active when we're not focused on the external world—that correlate strongly with overthinking tendencies.

“Overthinking is a maladaptive strategy to deal with anxiety. You overanalyze an issue to the point where it’s unhelpful and may even be harmful... When you do this, it can amplify feelings of danger, escalate your anxiety, and interfere with good judgment.” explains Shelly Smith-Acuña, PhD, professor and dean of the graduate school of professional psychology at the University of Denver.

This neurological insight helps explain why overthinkers often feel trapped in their thoughts despite recognising their circular nature. The very neural mechanisms that would typically allow for perspective-shifting become temporarily compromised.

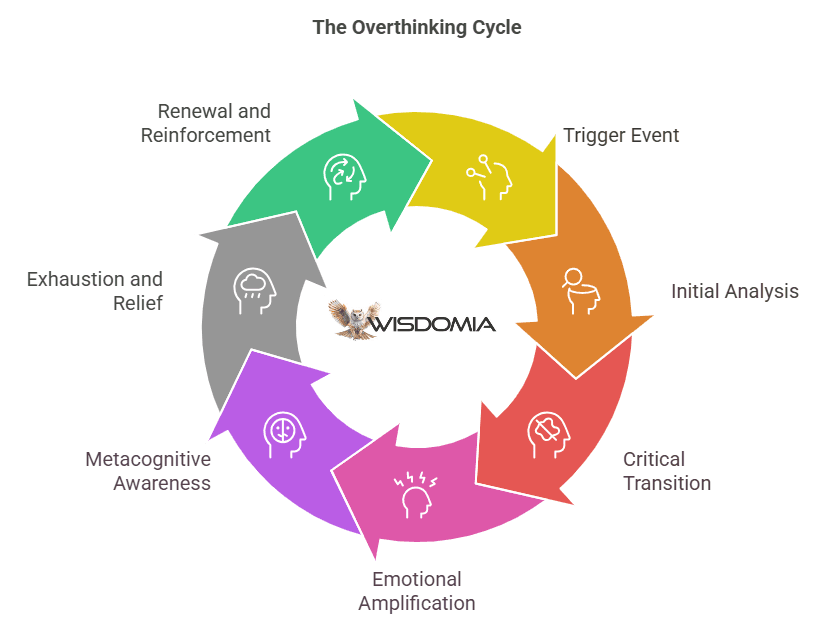

The Overthinking Cycle Decoded

Understanding overthinking requires recognising its cyclical nature. Through extensive research with chronic overthinkers, psychologists have identified a remarkably consistent pattern:

1. Trigger Event

The cycle typically begins with an ambiguous situation or emotion that contains sufficient uncertainty to warrant analysis. This might be a cryptic text message, an upcoming presentation, or even a passing comment from a colleague.

2. Initial Analysis

The mind engages in legitimate problem-solving, examining the situation from multiple angles. This phase often produces genuine insights and represents adaptive thinking.

3. The Critical Transition

The pivot into problematic overthinking occurs when analysis continues beyond the point of utility. Rather than concluding with actionable insights, the thinking process becomes self-perpetuating.

4. Emotional Amplification

As thinking persists without resolution, emotional distress increases. Anxiety, frustration, or insecurity intensifies, creating a neurochemical environment that further impedes cognitive flexibility.

5. Metacognitive Awareness

The overthinker becomes aware they're overthinking, adding an additional layer of self-criticism and anxiety. This awareness, rather than breaking the cycle, often becomes incorporated into it ("Now I'm overthinking about overthinking").

6. Exhaustion and Temporary Relief

Eventually, mental fatigue sets in. The overthinker may distract themselves or simply exhaust their cognitive resources, leading to temporary relief.

7. Renewal and Reinforcement

Without structural intervention, the pattern repeats when faced with the next ambiguous trigger, becoming more deeply entrenched with each cycle.

The Neurological Underpinnings

Recent advances in neuroscience offer fascinating insights into why certain individuals are more prone to overthinking than others. Functional MRI studies reveal that overthinkers typically demonstrate:

Hyperconnectivity between the prefrontal cortex (responsible for executive function) and the amygdala (our emotion-processing centre), creating a feedback loop where emotional responses trigger analysis, which in turn intensifies emotions.

Reduced activity in the anterior cingulate cortex, which typically helps resolve conflicting information and reach conclusions.

Dominant activation of the left prefrontal cortex, associated with analytical thinking, without corresponding activation in right prefrontal regions that facilitate holistic processing.

These neurological patterns help explain why traditional advice to "just stop thinking about it" proves so ineffective. The overthinker isn't choosing their thought pattern—they're experiencing the output of a particular neural configuration.

The Cultural Context: Why Overthinking Flourishes Today

Whilst the capacity for overthinking is wired into human cognition, contemporary conditions create a perfect storm for its proliferation. We navigate more information daily than our ancestors encountered in years, creating endless material for analysis. Simultaneously, the modern world presents unprecedented choice, depleting the cognitive resources that might otherwise regulate overthinking. Many modern occupations involve mental rather than physical labour, removing a natural circuit-breaker for rumination that physical exertion once provided.

Digital communication compounds these challenges, as text-based interactions strip away nonverbal cues, creating precisely the type of ambiguity that triggers overthinking. Additionally, many professional environments reward analytical thinking, inadvertently reinforcing overthinking tendencies in susceptible individuals.

This perspective offers a more compassionate framework for understanding overthinking—not as personal failure, but as a predictable response to unprecedented informational demands.

From Understanding to Wisdom: Breaking the Cycle

The path from overthinking to balanced cognition isn't achieved through simple techniques or quick fixes. Rather, it requires developing what might be called cognitive wisdom—the capacity to recognise when thinking serves us and when it doesn't.

Promising approaches combine neurological insights with practical interventions:

- Metacognitive Training: Learning to observe thoughts rather than becoming immersed in them. Mindfulness practices show particular promise in strengthening this capacity.

- Pattern Interruption: Implementing deliberate circuit-breakers when overthinking begins. Physical activity proves especially effective, redirecting blood flow from rumination-focused brain regions.

- Uncertainty Tolerance: Gradually building comfort with ambiguity through structured exposure to unresolved situations, supervised by skilled therapists.

- Perspective-Broadening: Techniques that activate right prefrontal regions, including certain creative activities and somatic practices.

- Cognitive Containment: Establishing dedicated "worry time" that constrains rumination to specific periods, preventing its spread throughout the day.

The emerging field of computational psychiatry offers particularly exciting possibilities. By modelling individual thought patterns, AI systems can identify early signs of unhelpful rumination and suggest personalised interventions before full overthinking cycles initiate.

The Higher Wisdom: Thinking in Service to Living

Perhaps the most profound insight emerging from overthinking research is philosophical rather than psychological. Human cognition evolved not as an end in itself, but to facilitate effective action and connection.

“Overthinking is like a rocking chair. It gives you something to do, but it doesn’t get you anywhere.” – Erma Bombeck

This perspective suggests that addressing overthinking requires more than techniques—it demands a fundamental reorientation toward thought itself. Rather than placing thinking at the centre of our identity and worth, we might instead view it as one aspect of a fuller human experience that includes embodiment, relationship, and direct experience.

Conclusion: Beyond the Thinking Trap

The good news emerging from laboratories and therapy rooms alike is that overthinking, however entrenched, remains malleable. Through deliberate practice, environmental modification, and sometimes technological assistance, individuals can develop a more balanced relationship with their analytical capacities.

The wisdom lies not in thinking more or thinking less, but in thinking purposefully—engaging our magnificent cognitive machinery when it serves us and allowing it to quiet when it doesn't. In this balance, we find not just relief from overthinking, but access to the full range of human capacities that excessive analysis often obscures.

For the chronic overthinker, this message offers hope: the same mind that creates elaborate worry can, with understanding and practice, create freedom from it. The path forward isn't one of cognitive constraint but of cognitive liberation—thinking deeply when appropriate and resting completely when not.

In this skillful navigation of our mental landscape, we discover a profound truth: some of our greatest insights arrive not when we're thinking hardest, but when we finally allow ourselves to stop.

previous

Core Sleep and Brain Function: What Neuroscience Tells Us

next

Teaching Feeling: How Educators Can Nurture Emotional Growth

Share this

Hind MoutaoikiI

R&D Manager

Hind is a Data Scientist and Computer Science graduate with a passion for research, development, and interdisciplinary exploration. She publishes on diverse subjects including philosophy, fine arts, mental health, and emerging technologies. Her work bridges data-driven insights with humanistic inquiry, illuminating the evolving relationships between art, culture, science, and innovation.