Understanding the Impact of Cognitive Biases on Your Daily Decisions

Sara Srifi

Tue Sep 16 2025

Explore cognitive biases and how they impact daily decisions. Learn about common biases like confirmation bias and anchoring, and discover strategies to mitigate their effects.

We all think we make sensible choices every day, right? Like picking what to wear or deciding if that online deal is actually good. But our brains are tricky things. They often take shortcuts, and these shortcuts, called cognitive biases, can really mess with our decisions. It's like having a little glitch in the system that makes us see things a bit skewed. This article is going to look at some of these common thinking traps and how they pop up in our lives, impacting everything from what we believe to how we spend our money.

Key Takeaways

- Cognitive biases are mental shortcuts that can lead to errors in judgment and decision-making.

- Confirmation bias makes us favour information that supports what we already believe.

- Anchoring bias means early information heavily influences our subsequent thoughts.

- The availability heuristic leads us to overestimate the importance of information that easily comes to mind.

- Recognising these common thinking patterns is the first step to making more balanced decisions.

Understanding Cognitive Biases: An Overview

What Are Cognitive Biases?

We all like to think we make decisions based on pure logic and facts. But the truth is, our minds often take shortcuts. These mental shortcuts, known as cognitive biases, are systematic patterns of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment. They're essentially ingrained ways our brains try to simplify information processing, helping us make sense of the world and reach conclusions quickly. While often useful, these shortcuts can sometimes lead us astray, influencing our perceptions and decisions in ways we might not even realise. These biases are not necessarily a sign of flawed thinking, but rather a consequence of how our brains are wired to handle vast amounts of information efficiently.

The Origins of Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases aren't just random errors; many have roots in our evolutionary past. In ancient times, quick decisions were often necessary for survival. For instance, a bias towards remembering threats more vividly than pleasant experiences could have been a life-saving mechanism. These mental shortcuts helped our ancestors navigate a dangerous world with limited resources. However, in today's complex society, these same mechanisms can sometimes lead to less rational outcomes. Understanding their origins helps us appreciate why they exist, even when they cause problems. The dual process theory offers a way to think about this, suggesting we have two modes of thinking: a fast, intuitive system (System 1) and a slower, analytical one (System 2). Many biases stem from over-reliance on System 1.

Cognitive Biases Versus Logical Fallacies

It's easy to mix up cognitive biases with logical fallacies, but they're distinct. A logical fallacy is an error in the structure of an argument, making it unsound. Think of it as a mistake in the reasoning process itself. A cognitive bias, on the other hand, is a pattern of thinking that leads to a faulty judgment or decision, often stemming from how we process information, our memory, or our attention. For example, focusing only on information that supports your existing beliefs is a cognitive bias (confirmation bias), whereas saying "everyone agrees with me, so I must be right" is a logical fallacy (appeal to popularity). While both can lead to incorrect conclusions, their source is different. Recognizing this distinction is key to improving our critical thinking skills and understanding how technological advancements are reshaping consumer behaviour.

Here's a simple breakdown:

| Feature | Cognitive Bias |

|---|---|

| Nature | Systematic error in thinking/judgment |

| Origin | Mental shortcuts, information processing |

| Example | Confirmation bias, anchoring bias |

| Focus | How we perceive and interpret information |

| Feature | Logical Fallacy |

|---|---|

| Nature | Error in the structure of an argument |

| Origin | Flawed reasoning or argumentation |

| Example | Ad hominem, straw man |

| Focus | The validity of an argument's structure |

Confirmation Bias: Reinforcing Our Beliefs

Seeking Information That Aligns With Our Views

Confirmation bias is a common mental tendency where we actively look for, interpret, and remember information that supports what we already believe. It’s like wearing blinkers; we tend to focus on evidence that fits our existing views, often ignoring or downplaying anything that contradicts them. This isn't usually a conscious choice; it's more of an automatic mental process. For instance, if you believe a particular political party is always right, you're more likely to seek out news sources that praise that party and dismiss any negative reports as biased or untrue.

Interpreting Information to Support Preconceptions

Beyond just seeking out agreeable information, confirmation bias also affects how we understand the data we encounter. We might interpret ambiguous evidence in a way that strengthens our current stance. Imagine you're testing a new product you're excited about. If the product has a minor flaw, you might see it as a small, easily fixable issue, whereas if you were already sceptical, you might view that same flaw as a sign of fundamental poor quality. This selective interpretation means that even neutral information can be twisted to fit our pre-existing narrative.

Recalling Information Selectively

Our memory also plays a role in confirmation bias. We tend to recall details that support our beliefs more easily than those that challenge them. If you've had a series of positive experiences with a certain brand, you're more likely to remember those instances when deciding whether to buy from them again, potentially forgetting any past negative encounters. This selective memory reinforces our positive associations and makes it harder to objectively assess the brand's overall performance.

Here's a simple way to think about it:

- Seeking: Actively looking for supporting evidence.

- Interpreting: Twisting ambiguous data to fit beliefs.

- Recalling: Remembering supporting facts more readily.

This bias can make it difficult to change our minds, even when presented with strong counter-arguments. It creates a feedback loop where our beliefs become more entrenched over time.

Anchoring Bias: The Power of First Impressions

Ever notice how the first price you see for something often sticks in your mind, even when you see other options? That's anchoring bias at work. It's our tendency to rely too heavily on that initial piece of information – the 'anchor' – when making decisions. This first impression can really shape how we view everything that follows.

How Initial Information Shapes Judgments

When we encounter new information, our brains often latch onto the first data point as a reference. This anchor then influences our subsequent judgments, sometimes without us even realising it. Think about a job interview; the candidate's initial answer to a tough question might set the tone for the interviewer's entire perception of them, regardless of how well they perform later.

Impact on Price Perception and Negotiations

This bias is particularly noticeable in pricing. A product marked down from a high original price often seems like a better deal, even if the sale price is still quite high. In negotiations, the first offer made can set the range for the entire discussion. If someone asks for a very high price initially, subsequent offers, even if lower, might still be higher than what the item is truly worth.

Here's a simple illustration:

| Item | Original Price | Sale Price | Perceived Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Watch | £500 | £350 | High |

| Headphones | £200 | £150 | Moderate |

| Book | £30 | £20 | Low |

In this table, the 'Original Price' acts as the anchor. The 'Sale Price' is then judged against this anchor, influencing our perception of the deal.

Over-reliance on Early Data Points

We often find it difficult to completely disregard that first piece of information. Even if we know it might be misleading, it still influences our thinking. This can lead us to make decisions that aren't entirely rational, simply because we're anchored to an initial figure or impression. It's like trying to steer a ship away from a reef, but the ship keeps drifting slightly back towards it because of the initial course.

Our minds are wired to seek patterns and reference points. When faced with uncertainty, that first piece of data provides a seemingly stable ground upon which to build our judgments, even if that ground is unstable.

To combat this, it's helpful to:

- Actively seek out a range of information before forming an opinion.

- Be aware of the first numbers or statements presented and question their validity.

- Consider the source of the initial information and their potential motives.

- Try to re-anchor yourself with new, objective data if the initial anchor seems unreliable.

Availability Heuristic: Judging by What Comes to Mind

Ever found yourself suddenly worried about flying after seeing a news report about a plane crash, even though you know statistically it's incredibly safe? That's the availability heuristic at play. It’s a mental shortcut where we judge the likelihood or importance of something based on how easily examples come to mind. If something is vivid, recent, or easily recalled, we tend to think it’s more common or probable than it actually is.

Seeking Information That Aligns With Our Views

This bias means we often overestimate the frequency of events that are easily recalled. Think about dramatic news stories – they stick with us. A single, memorable event, like a shark attack or a lottery win, can disproportionately influence our perception of how often such things happen, even if statistics tell a different story.

Interpreting Information to Support Preconceptions

Our minds favour information that is readily available. This can lead us to make decisions based on incomplete or skewed data. For instance, if you've recently heard several stories about people getting rich through cryptocurrency, you might overestimate the ease of making money in that market, ignoring the many who have lost money.

Recalling Information Selectively

The easier it is to recall an instance, the more likely we are to believe it is representative of reality. This can skew our understanding of risks and opportunities.

Consider the following:

- Media Influence: Sensationalised or dramatic events are more likely to be reported and replayed, making them highly available in our memory. This can lead to an inflated sense of risk for those events.

- Personal Experience: A single, impactful personal experience, whether positive or negative, can colour our judgment about similar situations in the future.

- Vividness: Information that is presented in a particularly striking or emotional way is more memorable and therefore more likely to be used in our judgments.

This reliance on readily available mental examples means our decisions can sometimes be based more on what we can easily remember than on a thorough, objective assessment of all available evidence. It’s a powerful shortcut, but one that can easily lead us astray if we’re not mindful of its influence.

For example, imagine you're deciding whether to invest in a particular company. If you can easily recall news articles or anecdotes about that company's recent successes, you might be more inclined to invest, even if a deeper analysis of its financial health reveals significant risks. The readily available positive information overshadows the less accessible, potentially negative data.

The Dunning-Kruger Effect: Overestimating Our Competence

Ever met someone who, despite clearly lacking skill, talks a big game about their abilities? That's likely the Dunning-Kruger effect in action. This bias means people with low competence in a particular area tend to overestimate their own knowledge and skill. It's a bit of a double whammy: not only are they not very good, but they also lack the insight to realise it.

Incompetence Leading to Overconfidence

At its core, the Dunning-Kruger effect suggests that the very skills needed to be competent are often the same skills needed to recognise competence. So, if you don't know much about a subject, you're less likely to spot your own errors or understand how much you don't know. This can lead to a misplaced sense of confidence. Think about learning a new skill, like trading. Initially, you might feel quite confident after a few small wins, but as you progress, you realise the vastness of what you still need to learn. Developing trading skills doesn't require being exceptionally smart; it's about gaining experience and educating your mind through regular practice and problem-solving. Overcoming challenges in trading builds intelligence and strategic thinking.

Recognising Skill in Ourselves and Others

Conversely, individuals who are genuinely skilled often underestimate their own abilities relative to others. They assume that tasks they find easy are also easy for everyone else. This can lead to them not seeking recognition or opportunities they deserve. The challenge, then, is to develop metacognition – the ability to think about one's own thinking. This involves honestly assessing our strengths and weaknesses, seeking feedback, and being open to learning.

The Impact on Performance Assessments

This bias can have significant implications, especially in performance reviews or team projects. A less competent individual might rate their own performance highly, while a more competent one might be overly modest. This mismatch can lead to inaccurate assessments and missed opportunities for development. It highlights the importance of using objective measures and seeking multiple perspectives when evaluating performance.

- Lack of self-awareness: The inability to accurately gauge one's own skill level.

- Overestimation: Believing one is more knowledgeable or capable than they actually are.

- Underestimation of others: Failing to recognise genuine expertise in more competent individuals.

- Difficulty in improvement: The inability to recognise one's own shortcomings hinders learning.

Negativity Bias: The Weight of the Bad

Prioritising Negative Experiences

It seems we're wired to pay more attention to the bad stuff. This tendency, known as negativity bias, means that negative experiences or information often stick with us more than positive ones, even if they're of equal intensity. Think about a fantastic holiday that was almost perfect, but for one minor hiccup – it's often that one small issue that we recall most vividly. This isn't just about remembering; it influences how we feel and react.

The Psychological Impact of Negative Information

This bias can have a significant psychological effect. When we encounter negative information, it can trigger a stronger emotional response. This means we might spend more time thinking about a critical comment than a compliment, or feel the sting of a small loss more acutely than the joy of a similar gain. It’s like our brains have a built-in alarm system that’s more sensitive to danger or problems than to good news.

Decision-Making Driven by Threat Avoidance

Because negative events often loom larger in our minds, they can steer our decisions. We might find ourselves making choices primarily to avoid potential negative outcomes, rather than to actively pursue positive ones. This can lead to a cautious approach, sometimes to the point of being overly risk-averse. For instance, someone might avoid investing in a potentially profitable venture because they're fixated on the possibility of losing money, even if the odds of success are high.

Here's a simple way to think about it:

- Positive Event: Receiving a compliment at work.

- Negative Event: Receiving constructive criticism at work.

While both are feedback, the criticism often gets more mental airtime. We might replay the criticism, analyse it, and worry about it, whereas the compliment might be acknowledged and then quickly set aside.

Our brains are naturally attuned to threats and problems. This evolutionary advantage helped our ancestors survive, but in modern life, it can sometimes lead us to overemphasise the bad and miss out on the good.

Sunk Cost Fallacy: The Trap of Past Investments

Have you ever found yourself continuing with something – a project, a relationship, even a bad film – simply because you’ve already put so much time or money into it? That’s the sunk cost fallacy at play. It’s a common cognitive bias where we feel compelled to continue an endeavour because of the resources we’ve already committed, rather than based on its future prospects. This tendency can lead us to make irrational decisions, sticking with failing ventures long after it makes sense to stop.

Continuing Due to Resources Already Expended

This bias often stems from a desire to avoid feeling like our past efforts were wasted. We’ve invested time, money, or emotional energy, and admitting that it was for naught can be difficult. Think about a business venture that isn't performing well. Instead of cutting losses, a manager might pour more funds into it, believing that if they just invest a little more, they can recoup the initial outlay. This is a classic example of letting past investments dictate future actions, rather than objectively assessing the current situation and potential for future success. It’s like trying to fix a leaky pipe with more tape when the pipe itself is fundamentally broken.

Difficulty in Cutting Losses

It’s human nature to dislike loss. The sunk cost fallacy amplifies this, making us particularly averse to acknowledging that a past decision was a mistake. We might tell ourselves, “I’ve come this far, I can’t stop now,” even if “this far” is leading us further away from our goals. This can manifest in personal life too; perhaps you’ve spent years studying a subject you no longer enjoy. The thought of abandoning that path, after all the effort, can be daunting, leading you to continue down a road that doesn't align with your current aspirations. Learning to accept that past investments are gone, regardless of future actions, is key to breaking free from this trap. It’s about recognising that the money or time is already spent, and the only decision left is what to do now.

Justifying Past Decisions Over Future Prospects

Often, the sunk cost fallacy involves a form of self-justification. We want to prove to ourselves and others that our initial decision was sound. This can lead to a distorted view of reality, where we focus on any small positive sign while ignoring larger negative trends. For instance, someone might continue to pour money into a failing car because they’ve already spent a significant amount on repairs, rather than considering the cost of a new, more reliable vehicle. The past expenditure becomes the primary driver, overshadowing a rational assessment of future costs and benefits. It’s important to remember that future decisions should be based on future outcomes, not on past commitments. We need to be able to touch the bars that hold us back and realise they are no longer necessary.

Here’s a simple way to think about it:

- Initial Investment: Time, money, effort put into an endeavour.

- Current Status: The endeavour is no longer viable or beneficial.

- The Fallacy: Continuing because of the initial investment, not future potential.

- Rational Action: Evaluate the future prospects independently of past costs.

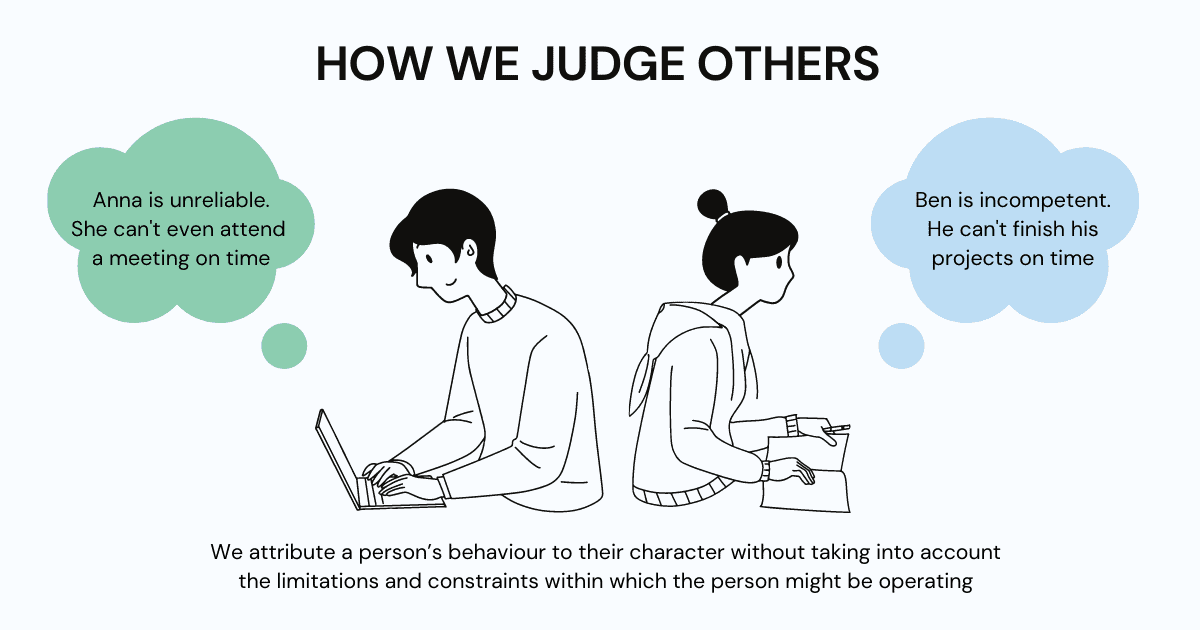

Fundamental Attribution Error: Judging Others Differently

Attributing Actions to Personality Over Situation

We all do it. Someone cuts you off in traffic, and your immediate thought might be, "What a rude, aggressive driver!" You’re likely attributing their behaviour to their personality – they’re just a bad person. This is the essence of the fundamental attribution error. It’s our tendency to overemphasise dispositional or personality-based explanations for others' behaviour while underemphasising situational explanations. It’s easier to blame the person than the circumstances.

Overlooking External Factors in Others' Behaviour

Think about a colleague who misses a deadline. Your first instinct might be to label them as lazy or disorganised. However, you might not consider that they could be dealing with a personal crisis, facing technical difficulties, or overloaded with work due to unforeseen circumstances. We often fail to give enough weight to the external factors that might be influencing someone else's actions. This can lead to unfair judgments and strained relationships.

The Impact on Interpersonal Judgments

This bias significantly shapes how we perceive and interact with others. When we consistently attribute negative behaviours to someone’s character, it can lead to:

- Misunderstandings: We might misinterpret someone’s intentions or capabilities.

- Prejudice: It can contribute to forming negative stereotypes about individuals or groups.

- Conflict: Unfair judgments can create friction and damage relationships, both personal and professional.

Consider a scenario where a student performs poorly on an exam. The fundamental attribution error might lead a teacher to believe the student is simply not bright or doesn't study enough, overlooking potential issues like test anxiety, lack of sleep, or a misunderstanding of the material that could be addressed with targeted support.

We are often quick to judge others based on their actions, but we tend to be far more forgiving of ourselves when we make similar mistakes. This difference in judgment highlights how our internal biases can colour our perception of the world and the people within it.

Cognitive Biases in Personal and Professional Life

Influence on Relationships and Social Interactions

Our personal connections and how we interact with others are surprisingly shaped by these mental shortcuts. For instance, confirmation bias can make us focus only on the good (or bad) traits of a partner, skewing our overall view. If we've recently had a disagreement, the availability heuristic might make us overestimate the likelihood of future problems, simply because that negative experience is fresh in our minds. It’s easy to fall into the trap of assuming others share our opinions, too, which can lead to misunderstandings.

Impact on Financial and Career Choices

When it comes to money and work, biases can really steer us wrong. Anchoring bias, for example, can mean we get stuck on an initial price or salary figure, even if circumstances change. We might hold onto a losing investment for too long because of the sunk cost fallacy – we've already put so much in, so we feel we can't stop now, even if it's not making sense. In our careers, the Dunning-Kruger effect might lead us to overestimate our own skills, making us less likely to seek out training or feedback that could actually help us improve. Focusing too much on the negatives at work, thanks to negativity bias, can also make us overlook opportunities or feel less satisfied than we might otherwise.

Shaping Health and Lifestyle Decisions

Even our health choices aren't immune. Confirmation bias can lead us to seek out information that supports our existing habits, whether they're healthy or not. If we hear a lot about a particular health risk in the news, the availability heuristic might make us think it's more common than it really is, leading to unnecessary worry or the adoption of extreme measures. It’s a constant balancing act to make decisions based on solid information rather than what readily comes to mind or what we already believe.

Strategies for Mitigating Cognitive Biases

It's quite natural for our minds to take shortcuts, but sometimes these mental shortcuts, known as cognitive biases, can lead us astray. While we can't switch them off entirely, there are practical ways to lessen their influence on our decisions. It's about becoming a bit more aware and a bit more deliberate in how we think.

Developing Self-Awareness and Reflection

The first step is simply knowing these biases exist and that you, like everyone else, are susceptible to them. Take a moment to think about your own thought processes. When you make a decision, especially a significant one, try to trace back why you arrived at that conclusion. Were you perhaps leaning towards information that already agreed with you? Did an initial piece of data heavily sway your opinion? Practising mindfulness, which is essentially paying attention to your thoughts without judgment, can help you catch these biases in action as they happen. It’s like developing a mental early warning system.

Seeking Diverse Perspectives and Feedback

It’s easy to get stuck in our own heads, surrounded by people who think similarly. To counter this, actively look for viewpoints that differ from your own. Talk to people with different backgrounds, experiences, and opinions. Read articles or books that challenge your existing beliefs. When you hear yourself saying, "This is the only way to see it," that’s a good sign to pause and ask, "What am I missing?" Asking trusted friends or colleagues for their take on a situation can also be incredibly helpful. They might spot a bias you've overlooked.

Utilising Data and Objective Decision-Making Tools

When possible, try to ground your decisions in facts and figures rather than just gut feelings or vivid examples. For important choices, especially in work or finance, setting clear, objective criteria beforehand can be very effective. For instance, if you're evaluating job candidates, having a standard set of questions and a scoring system can reduce the impact of personal impressions. Even simple tools like a pros and cons list, or a decision tree that maps out potential outcomes, can provide a more structured and less biased way to approach a problem.

Making a conscious effort to slow down your decision-making process can also make a significant difference. When faced with a choice, resist the urge to make a snap judgment. Taking a little time to reflect, perhaps even sleeping on it, allows your more rational thinking processes to engage and can help override impulsive, biased reactions.

The Evolutionary Roots and Modern Challenges of Bias

Evolutionary Advantages of Mental Shortcuts

Our brains are wired to make decisions quickly. Think about it – for much of human history, a slow decision could mean the difference between life and death. Our ancestors needed to react fast to threats, and these mental shortcuts, or biases, were incredibly useful. They helped us assess risks rapidly, stick together in groups, and generally survive. For instance, a bias that made us wary of anything new or different might have kept us from eating poisonous berries. Similarly, sticking with our own group, even if it meant being suspicious of outsiders, probably helped early humans cooperate and protect themselves.

- Negativity Bias: This made our ancestors hyper-aware of potential dangers, ensuring they didn't miss a predator lurking in the bushes.

- In-group Bias: Fostering loyalty and cooperation within a tribe was vital for shared defence and resource gathering.

- Availability Heuristic: Remembering vivid, recent events (like a dangerous animal encounter) allowed for quicker, albeit sometimes flawed, risk assessments.

Maladaptive Biases in Today's Complex World

While these shortcuts were once lifesavers, they can cause problems in our modern, complex world. We're bombarded with information from all sides, and the quick judgments that served us well in the past can now lead us astray. The very things that helped us survive as small tribes can now create divisions or lead to poor choices in areas like finance or relationships.

The sheer volume of information we encounter daily means our brains still rely on these shortcuts, but the context has changed dramatically. What was once a helpful filter can now become a barrier to clear thinking.

Navigating Information Overload

Today, we face a different kind of challenge: information overload. Social media algorithms, for example, often show us content that confirms what we already believe, creating echo chambers that reinforce our existing biases. This makes it harder to consider different viewpoints or to make decisions based on objective facts rather than what's easily recalled or most emotionally resonant. It requires a conscious effort to step outside these digital bubbles and seek out diverse perspectives.

Here's a look at how some biases can be problematic now:

- Confirmation Bias: In an age of endless online information, it's easy to find 'evidence' for any belief, making it harder to change our minds even when presented with facts.

- Availability Heuristic: Sensational news stories, while memorable, don't always reflect the actual probability of events, leading to skewed perceptions of risk.

- Anchoring Bias: In negotiations or purchasing decisions, the first piece of information we receive can disproportionately influence our final judgment, even if it's not entirely relevant.

Moving Forward: Living with Our Biases

So, we've looked at how our brains can play tricks on us, leading us down paths of thinking that aren't always the most logical. It's pretty clear that these mental shortcuts, or biases, pop up everywhere, influencing everything from what we buy to how we see other people. The good news is, we're not completely powerless against them. By simply knowing they exist and paying a bit more attention to our own thought processes, we can start to make more considered choices. It’s not about never being biased again – that’s probably impossible – but about being aware and making an effort to see things a little more clearly. Think of it as a continuous learning process, one that helps us make better decisions for ourselves and interact more thoughtfully with the world around us.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly are cognitive biases?

Cognitive biases are like mental shortcuts our brains take. They're not always wrong, but they can sometimes cause us to think or decide in ways that aren't entirely logical or fair. Imagine your brain trying to make sense of a lot of information really fast – these shortcuts help, but they can also lead to mistakes in how we see things.

Why do we have these biases?

These shortcuts often developed a long time ago to help our ancestors survive. For example, quickly assuming something is dangerous could save a life. While they were useful then, in today's world, they can sometimes lead us to make poor choices because the situations are so different.

Can you give an example of confirmation bias?

Certainly. Confirmation bias is when you tend to look for and believe information that already fits what you think. So, if you believe a certain sports team is the best, you'll likely pay more attention to news that says they're great and ignore anything that suggests they aren't.

What is the anchoring bias?

Anchoring bias means we often rely too much on the first piece of information we get. Think about when you're buying something. If the first price you see is very high, even a slightly lower price might seem like a good deal, even if it's still quite expensive.

How does the availability heuristic affect us?

This bias makes us think something is more likely to happen if we can easily recall examples of it. For instance, after seeing many news reports about plane crashes, you might feel flying is more dangerous than driving, even though statistics show otherwise. The dramatic examples are just easier to remember.

What is the sunk cost fallacy?

The sunk cost fallacy is when we keep putting effort or money into something just because we've already invested a lot, even if it's not working out. It's like finishing a really boring film because you've already watched half of it, instead of stopping and doing something you'd enjoy more.

How can we try to avoid these biases?

It's tricky to get rid of them completely, but we can try to be more aware of them. Taking time to think things through, looking for different opinions, and using facts and data instead of just gut feelings can really help. Asking others for their thoughts is also a good idea.

Are cognitive biases always a bad thing?

Not entirely. As mentioned, they often started as useful ways to make quick decisions. Sometimes, these shortcuts can help us act fast in urgent situations. The main issue is when they lead us to make unfair judgments or poor choices in everyday life without us realising it.

previous

Philosophical Questions That Have Shaped Human Thought

next

Unveiling the Deep Meaning: What Does the Cherry Blossom Truly Symbolise?

Share this

Sara Srifi

Sara is a Software Engineering and Business student with a passion for astronomy, cultural studies, and human-centered storytelling. She explores the quiet intersections between science, identity, and imagination, reflecting on how space, art, and society shape the way we understand ourselves and the world around us. Her writing draws on curiosity and lived experience to bridge disciplines and spark dialogue across cultures.