Why Do We Forget Future Tasks? The Science Behind Prospective Memory Failures

Hind MoutaoikiIR&D Manager

Tue Jul 01 2025

There's a particular sting that comes with forgetting something you absolutely meant to remember. Perhaps it was your mother's birthday, calling the doctor, or picking up milk on the way home. The intention was clear, the commitment genuine, yet somehow the task slipped through the cracks of consciousness like water through cupped hands. In that moment of realisation—often accompanied by a palm striking the forehead—we feel a familiar cocktail of frustration, guilt, and bewilderment. How could we simply forget?

This isn't a failure of character or intelligence. What you've experienced is a lapse in what psychologists call prospective memory—our ability to remember to perform intended actions in the future. Understanding why these failures occur isn't just intellectually fascinating; it's profoundly liberating. It reveals that our forgetfulness isn't a personal failing but a predictable consequence of how our minds work, and more importantly, it shows us how we might work with our brains rather than against them.

The Burden of Cognitive Load

One of the primary reasons prospective memory fails is what researchers call cognitive load—the mental effort required to process information and maintain awareness. Our brains, for all their sophistication, have limited processing capacity. When we're mentally stretched, something has to give, and prospective memory tasks often bear the brunt.

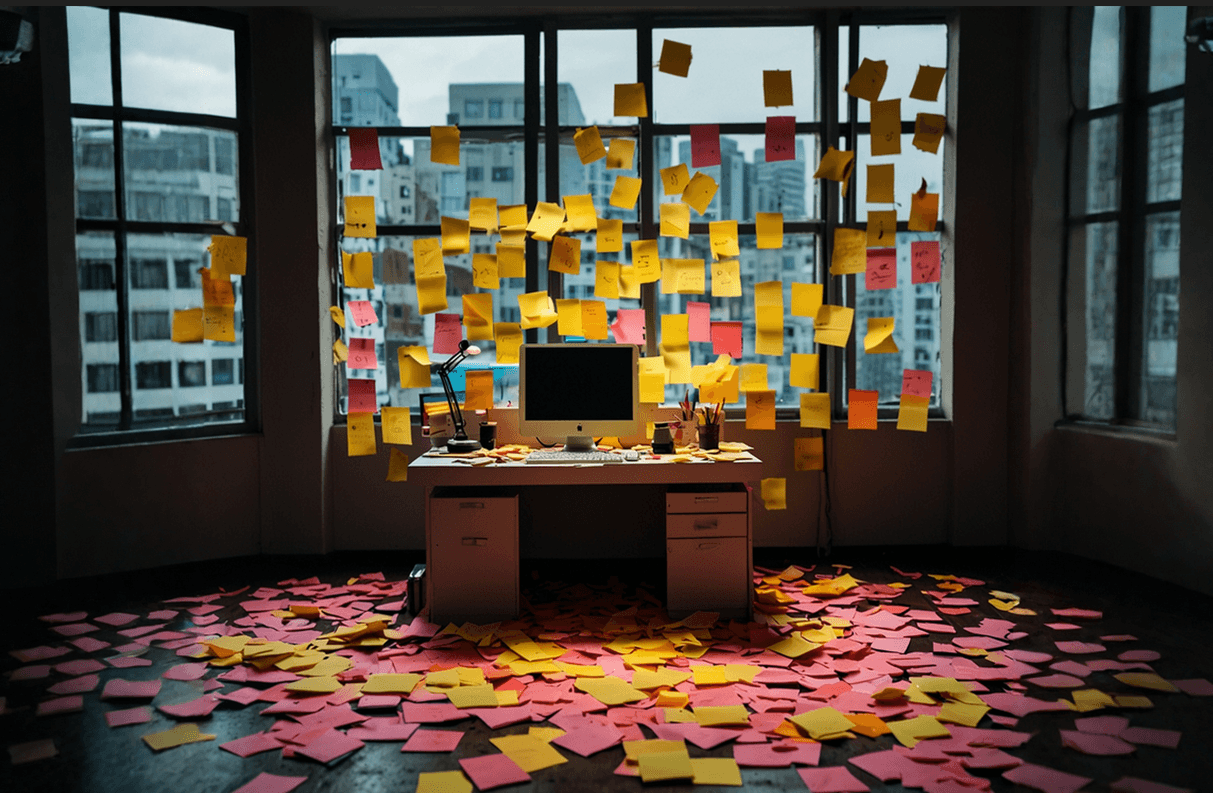

Think of your mind as a computer running multiple programmes simultaneously. When too many applications are open, the system slows down, and some processes may crash entirely. Similarly, when we're juggling work pressures, family concerns, financial worries, and the endless stream of modern life's demands, our capacity to monitor future intentions becomes compromised.

This isn't a design flaw—it's a feature. Our brains prioritise immediate, pressing concerns over future intentions because, evolutionarily speaking, the present moment often determined survival. The rustling in the bushes demanded immediate attention; remembering to gather berries later could wait. We've inherited this bias towards the immediate, which serves us well in crises but can leave us vulnerable to prospective memory failures in our complex modern world.

The Paradox of Automaticity

Here's where things become particularly interesting: the tasks we forget most often are precisely those that should be easiest to remember. Research shows that we're more likely to forget routine, habitual actions than novel, important ones. This seems counterintuitive—surely familiar tasks should be easier to remember?

The answer lies in the paradox of automaticity. When actions become routine, our brains process them with less conscious attention. Taking your daily medication, for instance, can become so automatic that you genuinely cannot remember whether you've taken it today. Your brain, in its efficiency, has relegated the task to background processing, where it becomes vulnerable to interruption and forgetting.

This explains why you might forget to post a letter that's been sitting by your keys for a week, yet remember to buy flowers for your partner's birthday—a novel task that engages your conscious attention more fully. The familiar becomes invisible to our monitoring systems, whilst the unusual captures our cognitive spotlight.

The Emotional Landscape of Intention

Our emotional state profoundly influences prospective memory. When we're stressed, anxious, or overwhelmed, our ability to monitor future intentions diminishes significantly. This isn't simply because stress is distracting—though it certainly is—but because emotional states alter the very neural networks responsible for prospective memory.

Chronic stress, in particular, can impair the prefrontal cortex's ability to maintain awareness of future goals whilst managing present demands. This creates a vicious cycle: we forget important tasks, which increases our stress, which makes us more likely to forget future tasks. Breaking this cycle requires not just better memory strategies, but attention to our emotional wellbeing.

Conversely, positive emotions can enhance prospective memory. When we're in a good mood, we're more likely to remember future intentions, partly because positive emotions broaden our attention and make us more aware of environmental cues. This suggests that our mental state is not just a backdrop to memory—it's an active participant in the process.

The Tyranny of Implementation Intentions

One of the most robust findings in prospective memory research concerns the power of implementation intentions—specific plans about when, where, and how we'll perform a future action. Simply intending to "call the bank" is far less effective than deciding "I will call the bank at 2 PM from my desk after finishing lunch."

Why do these specific plans work so well? They create what researchers call "cue-action linkages" in the brain. By specifying exactly when and where we'll act, we essentially programme our minds to recognise the relevant environmental cues and trigger the appropriate response. It's like setting a mental alarm that goes off not at a specific time, but in a specific context.

This discovery has profound implications for how we structure our lives. Rather than relying on our general intention to remember, we can harness the brain's natural tendency to respond to environmental cues. The key is being specific about the context in which we'll act.

The Digital Dilemma

Our relationship with technology adds another layer of complexity to prospective memory. On one hand, smartphones and digital calendars can serve as external memory aids, freeing our minds from the burden of constant monitoring. On the other hand, our dependence on these devices may be weakening our natural prospective memory abilities through a phenomenon psychologists call "digital amnesia."

When we know information is readily available externally, our brains don't bother encoding it as thoroughly. This isn't necessarily problematic—it's a form of cognitive efficiency. But it does mean that when our digital systems fail, we're left more vulnerable than previous generations who relied more heavily on internal memory systems.

The challenge isn't to reject technology, but to use it wisely. Digital tools work best when they complement rather than replace our natural memory processes. Setting a phone reminder for "buy milk" is helpful, but combining it with a specific implementation intention—"when I leave the office, I will check my phone for errands"—is even more effective.

The Neuroscience of Aging and Memory

As we age, prospective memory faces additional challenges. The prefrontal cortex, so crucial for monitoring future intentions, is particularly vulnerable to age-related changes. Processing speed slows, and our ability to divide attention between current tasks and future goals diminishes.

But here's the encouraging news: whilst some aspects of prospective memory decline with age, others remain remarkably stable. Event-based prospective memory—remembering to do something when a specific cue appears—shows less age-related decline than time-based prospective memory—remembering to do something at a specific time.

This suggests that as we age, we can adapt our memory strategies to work with our changing capabilities. Rather than fighting against natural changes, we can learn to structure our environments and intentions in ways that support our evolving cognitive strengths.

Strategies for the Future-Minded

Understanding the science of prospective memory failures isn't just academically interesting—it's practically transformative. Armed with this knowledge, we can develop strategies that work with our brain's natural tendencies rather than against them.

- First, embrace the power of external cues. Place objects in unusual locations where they'll capture your attention. Put your umbrella by the door when rain is forecast. Leave your library books by your car keys. Your environment can become an extension of your memory system.

- Second, reduce cognitive load wherever possible. When your mind is cluttered with competing demands, prospective memory suffers. This might mean saying no to additional commitments, delegating tasks, or simply accepting that some periods of life require more external memory support than others.

- Third, create specific implementation intentions. Transform vague goals into concrete plans with clear contextual cues. Instead of "I must remember to exercise more," try "After I have my morning coffee, I will put on my trainers and go for a walk around the block."

- Fourth, use the testing effect to your advantage. Regularly rehearse your future intentions, not just by thinking about them, but by mentally simulating the context in which you'll need to remember. This strengthens the neural pathways between cues and actions.

A Future of Enhanced Remembering

As our understanding of prospective memory deepens, we're developing increasingly sophisticated strategies for supporting this crucial cognitive function. Researchers are exploring everything from brain training programmes to smart home technologies that can serve as environmental memory cues.

But perhaps the most promising developments are those that acknowledge the fundamentally human nature of memory. We're not computers that can be programmed for perfect recall. We're meaning-making creatures whose memory systems evolved to help us navigate social relationships, learn from experience, and pursue long-term goals.

The future of prospective memory enhancement lies not in trying to eliminate all forgetting—an impossible and perhaps undesirable goal—but in understanding our cognitive architecture well enough to design lives that support our natural memory processes. This means cities planned with human memory limitations in mind, workplaces that account for cognitive load, and technologies that enhance rather than replace our innate capabilities.

previous

Review: Businessabc AI Global Summit 2025

next

The Psychology of Listening: How to Deepen Our Listening

Share this

Hind MoutaoikiI

R&D Manager

Hind is a Data Scientist and Computer Science graduate with a passion for research, development, and interdisciplinary exploration. She publishes on diverse subjects including philosophy, fine arts, mental health, and emerging technologies. Her work bridges data-driven insights with humanistic inquiry, illuminating the evolving relationships between art, culture, science, and innovation.