How Unity in Art Creates Visual Comfort and Balance

Maria Fonseca

Mon Jul 07 2025

Reflections on Wholeness, "I Am," and the Mirror of the Self

In a world saturated with fragmented images and overwhelming stimuli, the presence of unity in art offers not just visual comfort but a deeper sense of inner harmony. Unity is more than a design principle—it is an echo of something essential to being. When we encounter unity in a painting, a building, or a piece of music, we often feel a quiet stillness, as if something in us is being recognized.

This feeling is not just intellectual or emotional. It is existential. It invites the question: What is unity, and how does it mirror the deeper “I am” that transcends personal identity?

Unity as a Felt Sense

In artistic terms, unity refers to the visual coherence and harmony among elements in a composition. It emerges when the parts relate to the whole in a meaningful way—when repetition, rhythm, balance, and variation work together to create a sense of wholeness. Yet unity also gestures toward something deeper: an inner consonance between the observer and the observed.

This is why works of art that possess unity don’t just “look right”—they feel right. They offer a visual homecoming, a soft landing place for the mind and heart.

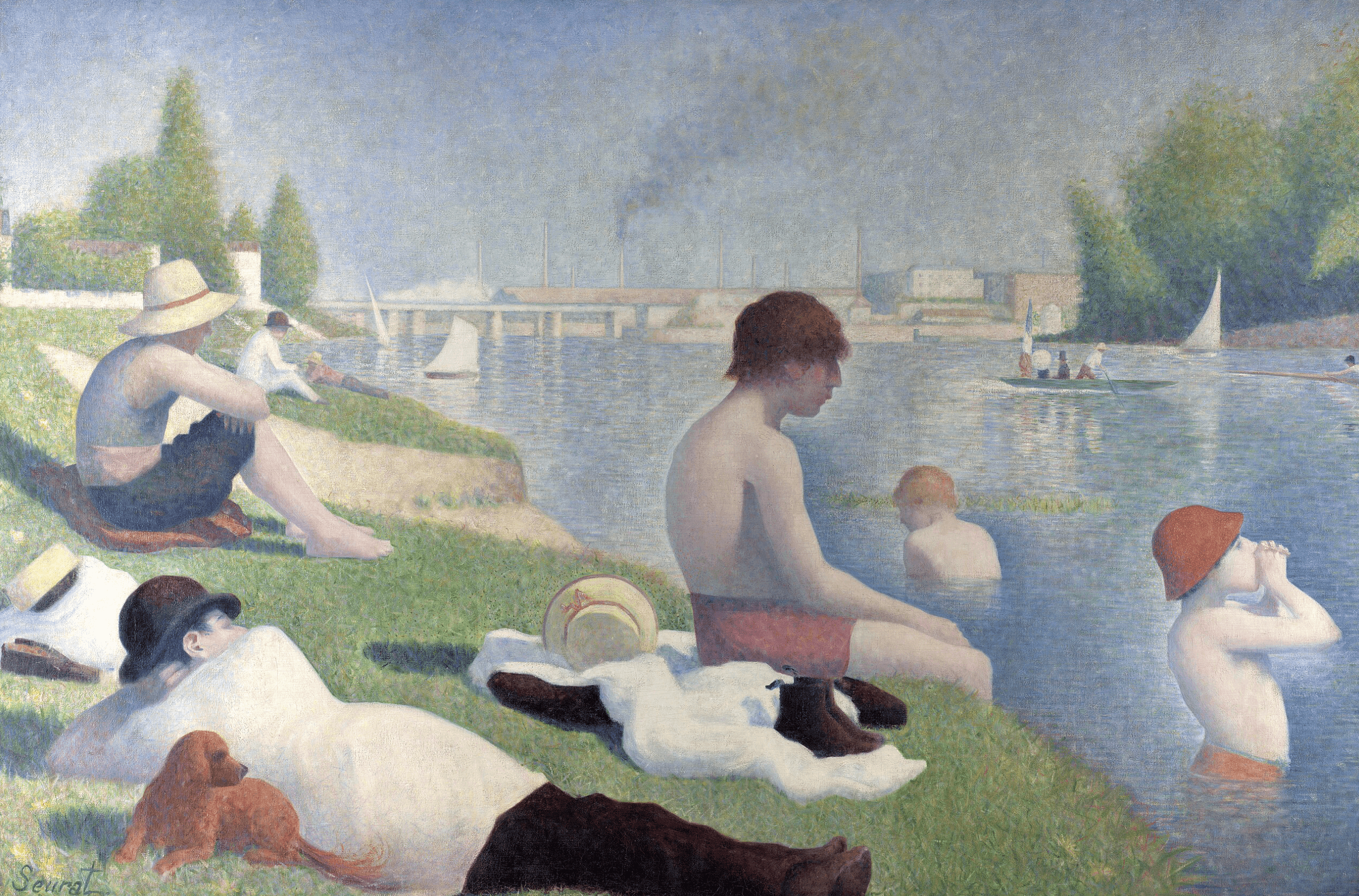

Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières: A Pointillist Unity

Georges Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières (1884) is a powerful example of unity through method and meaning. Using pointillism—a technique of applying small dots of color that blend in the viewer’s eye—Seurat created not just an image but an atmosphere. The balance between form, color, and light yields a scene of tranquil simplicity and order.

Despite the modern industrial backdrop, the bathers rest in calm awareness of each other and the river. There is rhythm in the spacing, repetition in the postures, and a subtle geometry anchoring the composition. Nothing is random. The painting breathes with quiet unity, offering the viewer a similar sense of inner stillness.

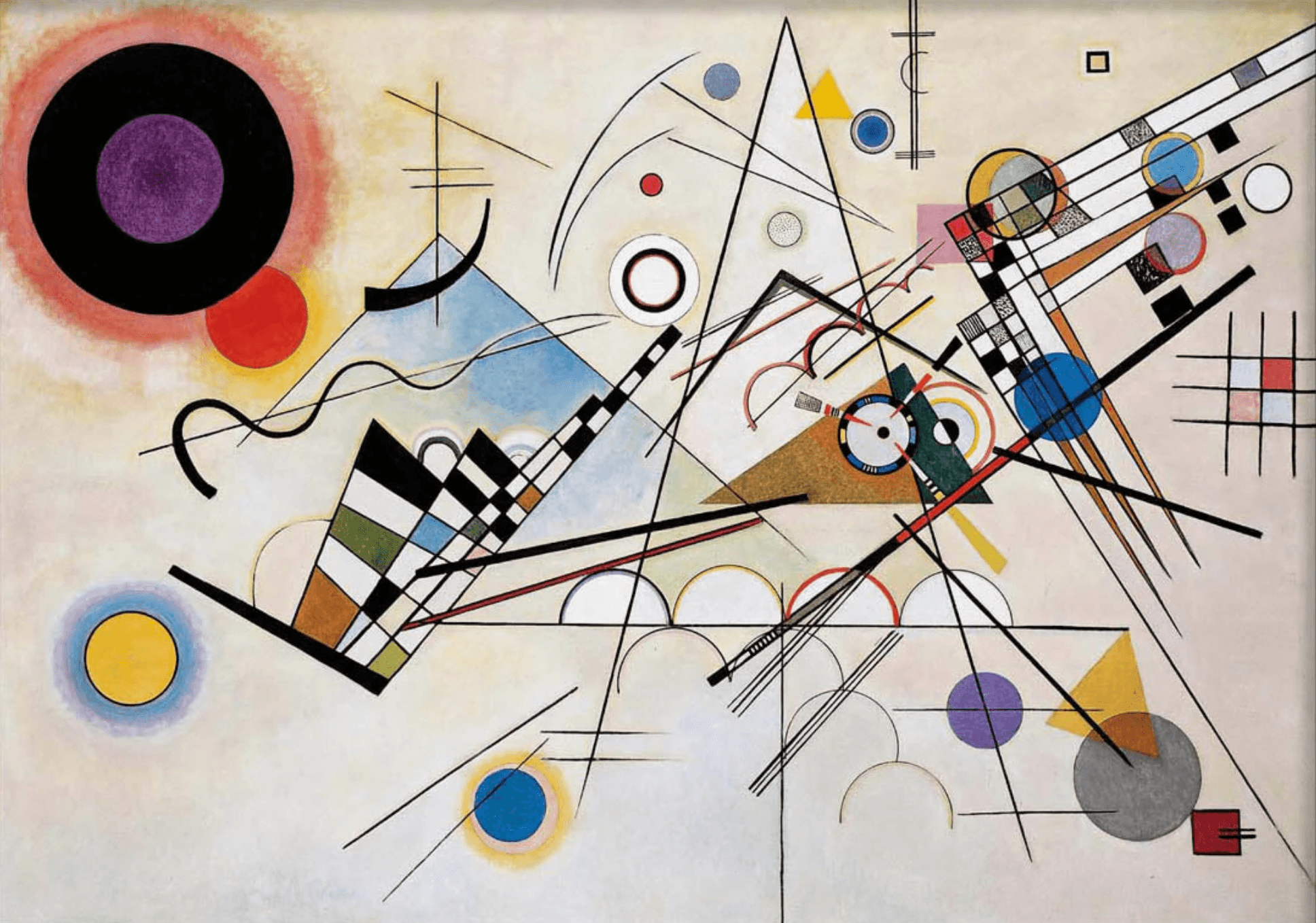

Kandinsky and Inner Necessity

For Wassily Kandinsky, unity arose not from imitation of nature but from resonance with “inner necessity.” In his abstract compositions, he sought to make visible the emotional and spiritual harmonies that structure human experience. In Composition VIII, the visual elements—circles, lines, colors—exist in dynamic interplay, yet the whole vibrates with a kind of cosmic balance.

Kandinsky believed that every true work of art was a reflection of a spiritual reality beyond the personal self. This deeper “I am” is not egoic but universal—a spark of the infinite that longs for expression through form.

Christopher Alexander: Unity as “The Quality That Has No Name”

Christopher Alexander, an architect and visionary thinker, approached unity not as an aesthetic trend but as an ontological principle — something essential to the fabric of life itself. In The Nature of Order, he describes a “quality that has no name,” later calling it “wholeness” or “life.” This quality is something we feel intuitively — it brings peace, stillness, and a quiet joy when we encounter it in spaces, objects, or images.

One of the most profound tools Alexander offers for recognizing this unity is “The Mirror of the Self” test.

The Mirror of the Self Test

In this experiment, Alexander would present people with two objects — sometimes two similar items like a salt shaker and a ketchup bottle — and ask a simple question:

“Which of these two is a better mirror of your true self?”

He discovered that people of all backgrounds and professions could answer this question immediately and with deep certainty — and that most people tended to agree. The object that was a "better mirror" typically had qualities of calmness, harmony, proportion, and subtle complexity. It wasn’t flashy or contrived. It felt alive.

This test reveals something extraordinary: unity resonates with us on a deep, almost spiritual level. The preference is not about style or fashion, but about what feels aligned with the deeper structure of life — with how nature and the human soul evolve in harmony.

The Salt Container and the Ketchup Jar

A famous version of this test involved presenting a humble hand-made salt container next to a mass-produced ketchup bottle. Most people, when asked which was a better mirror of their true self, chose the salt container. Why?

Because it had subtle asymmetries, textures, and form that showed care and organic shaping. It was clearly made by a human hand with attention and love. In contrast, the ketchup bottle — though perfectly functional and efficient — felt lifeless. It was created by a process of industrial optimization, not emotional or spiritual intention.

Here, unity is not about symmetry or perfection. It’s about deep coherence — between form, material, purpose, and feeling. The salt container expresses this coherence. It feels like it belongs, not only in the world but in your world. It reflects you.

Alexander’s insight is that this feeling of rightness is not subjective whim — it is objective and testable. And when applied to architecture, art, or technology, it leads to designs that nourish rather than exhaust us.

Unity and the Transcendent “I Am”

To encounter unity is to momentarily see the world—and ourselves—whole. It is not the unity of control or perfection, but of deep participation. The artist, the viewer, and the artwork all become part of a greater rhythm. In this state, the boundary between self and world softens.

The “I am” that resonates with true art is not the egoic self, but something vaster—a consciousness that recognizes life in all things. Unity in art reflects this truth. It reminds us that we are not fragmented, isolated beings but part of a living, breathing cosmos.

Art as a Mirror of Wholeness

Whether in Seurat’s luminous pointillism, Kandinsky’s spiritual abstraction, or Alexander’s living geometry, unity in art serves as a mirror. It invites us to return to what is essential—to the parts of ourselves that long for peace, connection, and belonging.

To seek unity in art is to seek ourselves, not in a narcissistic way, but in the truest sense: a coming home to the “I am”that sees, feels, and knows beyond the surface.

And in that moment of recognition, visual comfort becomes spiritual clarity. The world makes sense again—not because it is simple, but because it is whole.

previous

Minimalist Masters: How Artists Created Simple and Yet Deeply Meaningful Paintings

next

The Book of Human Stupidity - Part 1

Share this

Maria Fonseca

Maria Fonseca is an interdisciplinary educator, writer, artist and researcher whose work bridges the realms of academic knowledge, community engagement, and spiritual inquiry. With a background in Fine Art and a doctorate in creative practice, Maria has spent over a decade exploring the intersections of human experience, cultural meaning, and collective transformation.

More Articles

World Labs: What Fei-Fei Li's Spatial Intelligence Platforms Means for the Future of AI

Are the Laws of the Universe Discovered or Imposed?

Chinese New Year 2026: Galloping Into the Year of the Fire Horse

The Machiavellian Principles Applied In An AI Hallucination Time (Part 5)

The Machiavellian Principles Applied In An AI Hallucination Time (Part 4)