Cosmic Consciousness: A Journey Through Time, Thought, and Being

Maria Fonseca

Mon Jul 28 2025

This article follows the story of how people have tried to understand a special kind of awareness called cosmic consciousness—a deep feeling of being connected to everything. It starts with early thinkers like William James and Richard Bucke, who explored spiritual experiences and moments of expanded awareness. Later, others like Carl Jung, Teilhard de Chardin, and Fritjof Capra added ideas from psychology, science, and evolution. Today, thinkers like Bernardo Kastrup continue the conversation, showing how ancient wisdom and modern science might both point to a universe filled with consciousness.

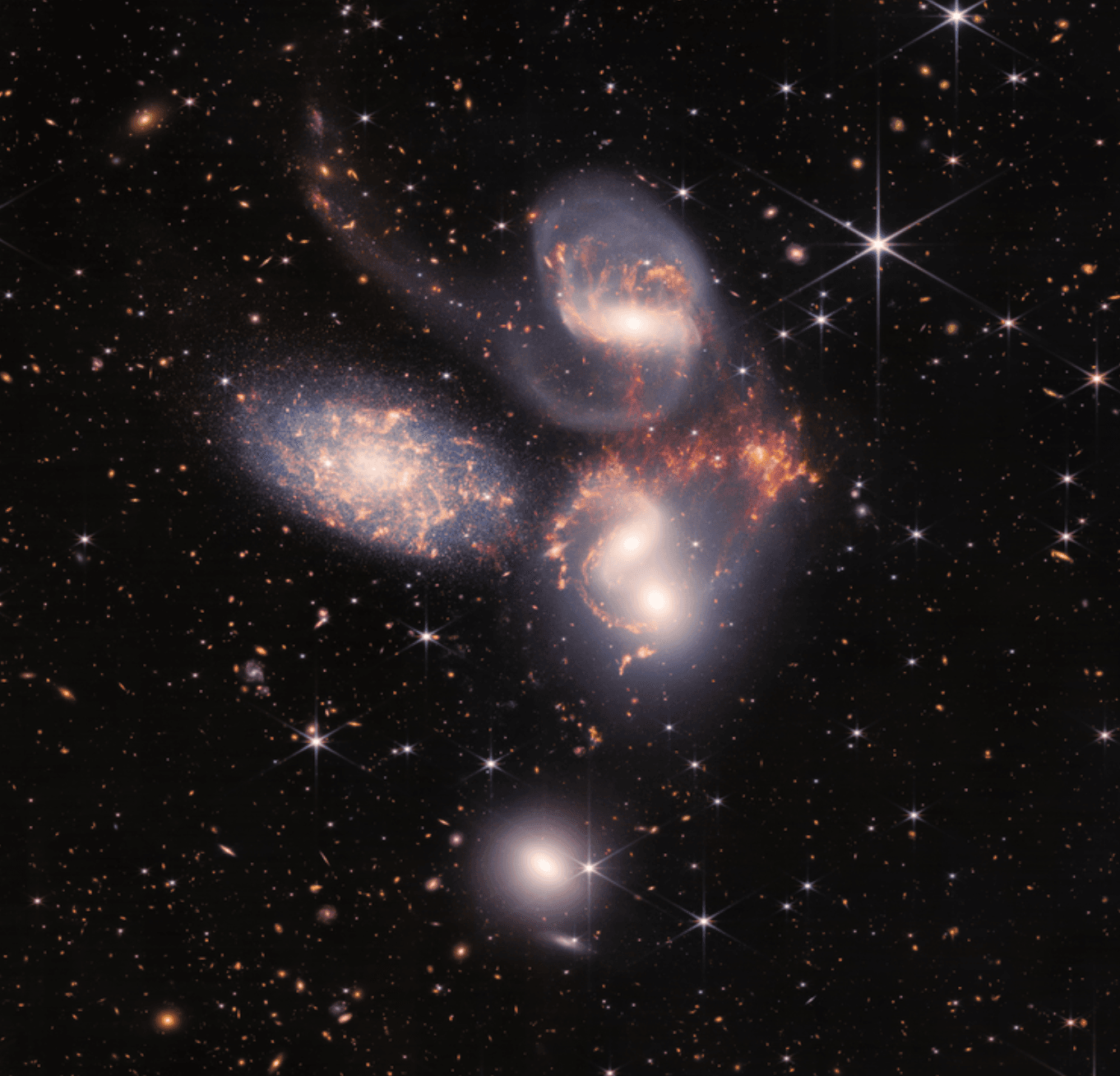

As the James Webb Space Telescope beams back its dazzling images of galaxies born billions of years ago, we find ourselves gazing not just outward, but inward. The sheer scale and beauty of the cosmos stir something primal in us—a sense of awe, wonder, and an age-old question: Is the universe just matter in motion, or could it somehow be alive, aware, even conscious? While science seeks to map the physical fabric of space-time, another journey has been unfolding in parallel: the human attempt to understand consciousness not merely as a private, biological phenomenon, but as something that might be woven into the cosmos itself.

This idea—that awareness might not be limited to brains but could be a fundamental aspect of reality—has surfaced again and again across time. From early psychological pioneers to modern philosophers and systems theorists, the concept of cosmic consciousness has been explored as both mystical experience and philosophical insight. Its evolution reflects our longing to understand not just what the universe is, but what it means to be part of it.At the threshold between science and spirituality lies a concept as elusive as it is compelling: cosmic consciousness. Not a theory in the traditional sense, but a lineage of insight, intuition, and inquiry, cosmic consciousness refers to a heightened awareness of the interconnectedness of all life—an awakening to the universe as conscious, or at least consciousness-infused. From early psychological pioneers to modern-day philosophers on Arctic cruises, this idea has quietly shaped our understanding of mind, self, and cosmos. Its evolution traces not just intellectual history, but a deepening yearning for integration between empirical knowing and perhaps mystical being.

William James: The Varieties of Awakening

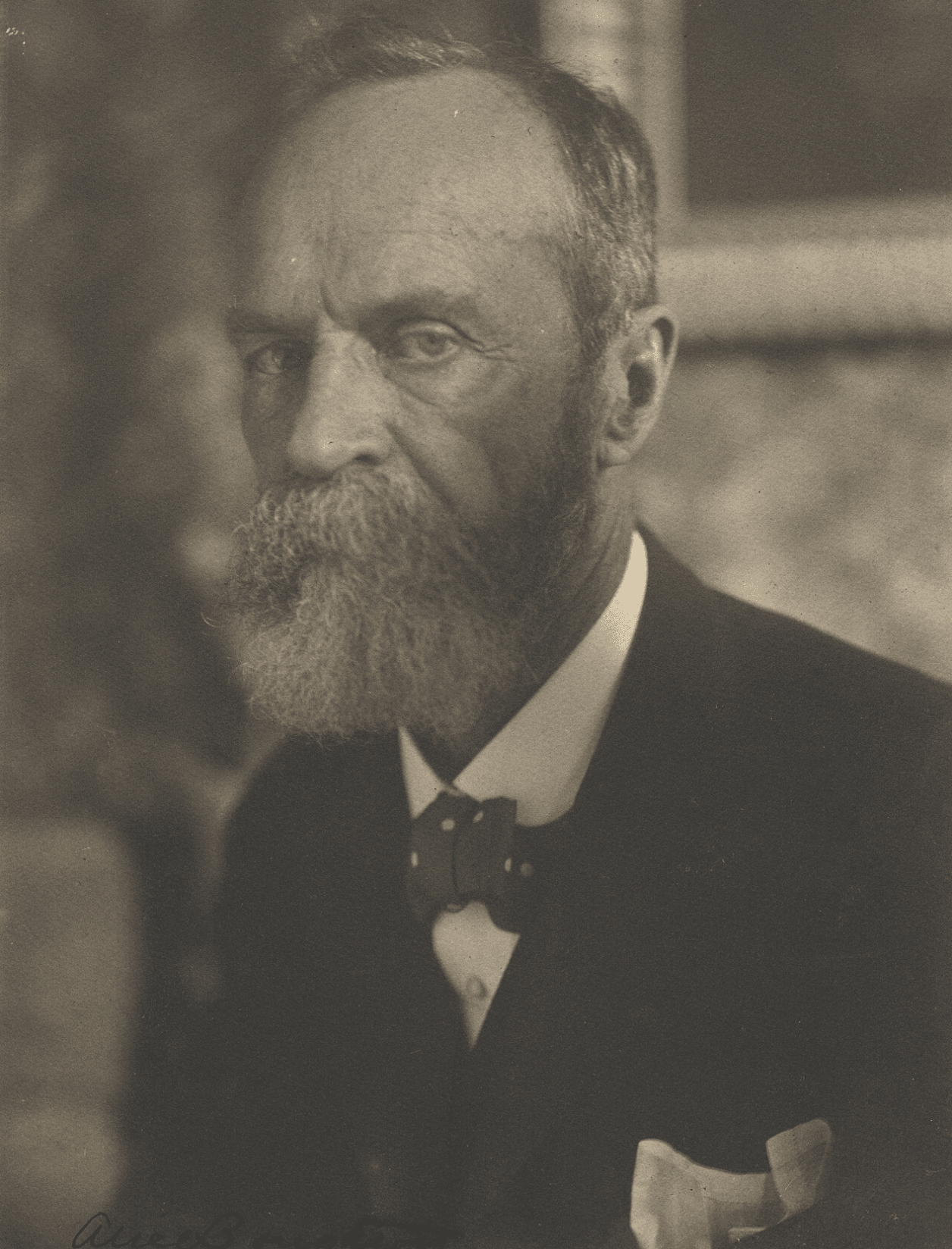

The story arguably begins in the late 19th century with William James, whose The Varieties of Religious Experience(1902) laid the groundwork for studying mystical states within a proto consciousness studies framework. James approached altered states of consciousness not as anomalies to be pathologized, but as legitimate modes of insight. He was fascinated by experiences of unity, timelessness, and a felt presence of the divine—experiences that often transcended traditional religious language and bordered on what we might call cosmic consciousness.

James coined the term "noetic quality" to describe the undeniable knowing that accompanies these mystical experiences. He wrote of the “oceanic feeling”—a sense of being part of something far vaster than oneself. For James, these experiences weren’t proof of metaphysical truths, but evidence of the mind’s extraordinary capacity to perceive beyond its ordinary boundaries. He respected what he called "radical empiricism," a willingness to take all experience seriously—including the spiritual and mystical—rather than filtering reality through rigid materialist assumptions.

Richard Maurice Bucke: Naming the Unnameable

While James was theorizing from a psychological perspective, Richard Maurice Bucke was experiencing the phenomenon firsthand. A Canadian psychiatrist, Bucke had a transformative experience one night while riding in a horse-drawn carriage. He described being filled with a sense of inner light, unity, and knowing that all was well—a moment of ecstasy that changed his life. In 1901, he published Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind, a book that sought to map this new dimension of consciousness as a stage of human evolution.

Bucke believed that just as humanity evolved from simple sensory awareness to self-consciousness, it was now moving toward a third stage: cosmic consciousness. He saw figures like Buddha, Jesus, and Dante as exemplars of this higher awareness, and believed it would eventually become widespread, transforming human society. While some dismissed his claims as mystical excess, Bucke’s vision resonated with those who sensed consciousness was more than a byproduct of the brain—it was, perhaps, the very fabric of the cosmos, and we were just beginning to touch its depths.

Carl Jung: The Collective Within

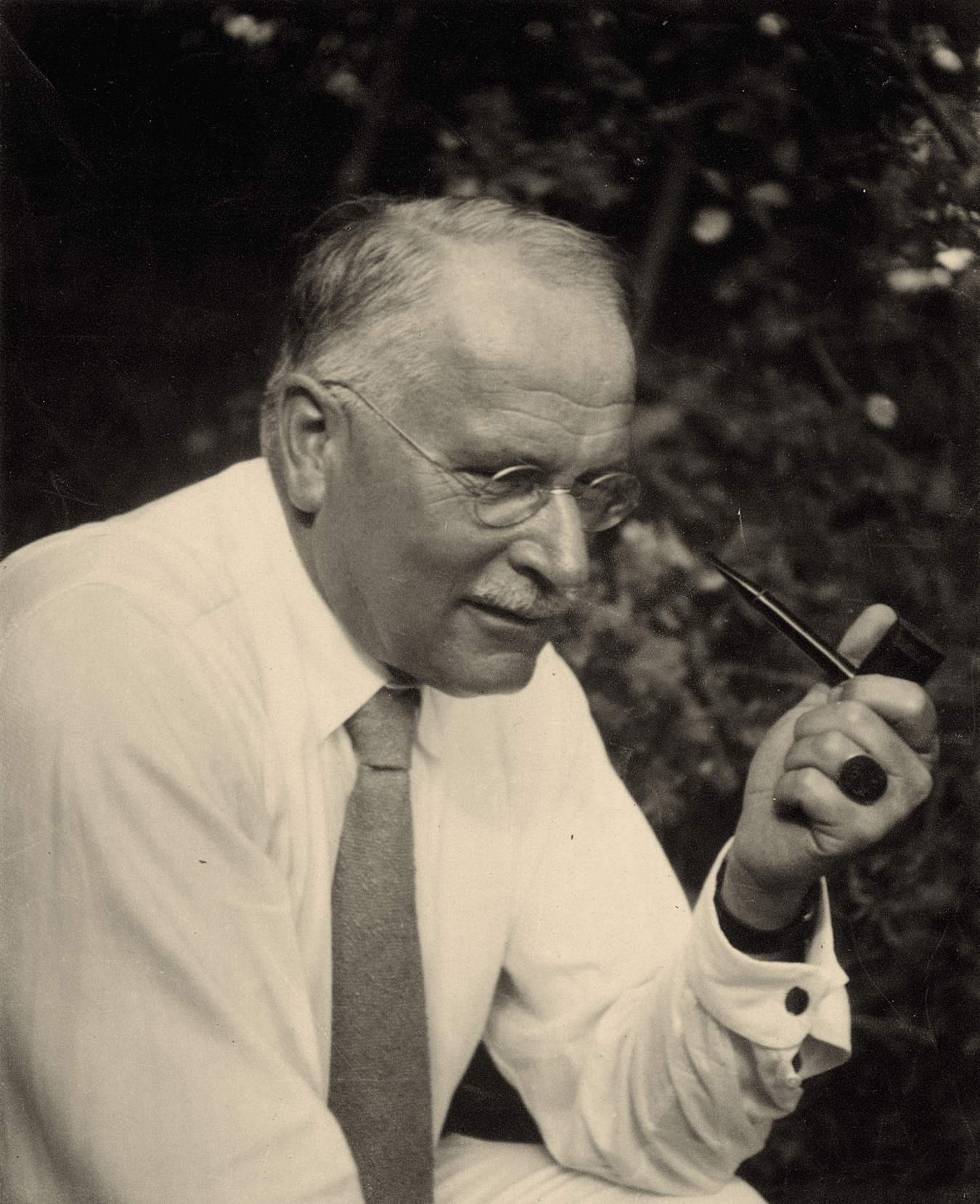

In the early 20th century, Carl Gustav Jung brought the conversation inward and downward, into the realm of the unconscious. Jung’s notion of the collective unconscious suggested that human beings share a deep psychic reservoir—archetypal patterns and symbolic forms that span cultures and epochs. While he did not use the term cosmic consciousness, Jung’s work suggested that individual consciousness was a node in a far larger psychic web.

Jung spoke of the Self—not the ego, but a larger organizing principle that integrated the conscious and unconscious mind, and hinted at transpersonal dimensions. In his late works, particularly Mysterium Coniunctionis, Jung moved closer to a mystical vision of reality, describing the individuation process as a sacred journey toward wholeness. For Jung, to become whole was to recognize one’s embeddedness in the cosmos—not as an isolated ego, but as a spark within a vast, living order.

Teilhard de Chardin: The Evolution of the Spirit

As Jung explored the inner worlds, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin offered a cosmic map of consciousness as evolution itself. A Jesuit priest, paleontologist, and visionary thinker, Teilhard sought to reconcile science and faith in a single, unfolding narrative of becoming. In The Phenomenon of Man (1955), he introduced the concept of the noosphere—a global envelope of thought and consciousness developing through and beyond the biosphere.

Teilhard envisioned evolution not just as a physical process, but as a spiritual ascent, culminating in what he called the Omega Point: the convergence of all consciousness into a unified divine awareness. For him, the universe was not a cold mechanism, but a spiritual organism moving toward increasing complexity, consciousness, and communion. In this view, cosmic consciousness wasn’t just a rare state of mind—it was the destiny of the human species.

Teilhard’s ideas were too radical for his time; the Catholic Church forbade him from publishing his major works during his lifetime. But posthumously, his thought found resonance among spiritual seekers, process philosophers, and even systems theorists who saw in his work a profound attempt to articulate a sacred science.

Ken Wilber: Integral Maps and Spectrums of Being

Fast forward to the late 20th century, and Ken Wilber emerges as a synthesizer of many traditions. A philosopher, psychologist, and theorist of consciousness, Wilber developed what he called the Integral Model—a framework that incorporates developmental psychology, systems theory, Eastern mysticism, and Western science. In The Spectrum of Consciousness and A Brief History of Everything, Wilber maps stages of consciousness from pre-personal to personal to transpersonal—and ultimately to what might be called cosmic awareness.

Wilber’s genius lies in creating models that integrate the insights of mysticism with the rigor of science. He argues that consciousness evolves both individually and collectively, and that human beings can access higher states of awareness through contemplative practice, ethical development, and intellectual clarity. His "four quadrants" model recognizes that consciousness is not only an inner experience but is shaped by culture, behavior, and systems.

Though some criticize his work as overly schematic, Wilber’s contributions remain essential for anyone trying to bridge science and spirit without collapsing one into the other. He insists that transcendence must include—not bypass—our psychological and social development.

Fritjof Capra: The Systems Turn

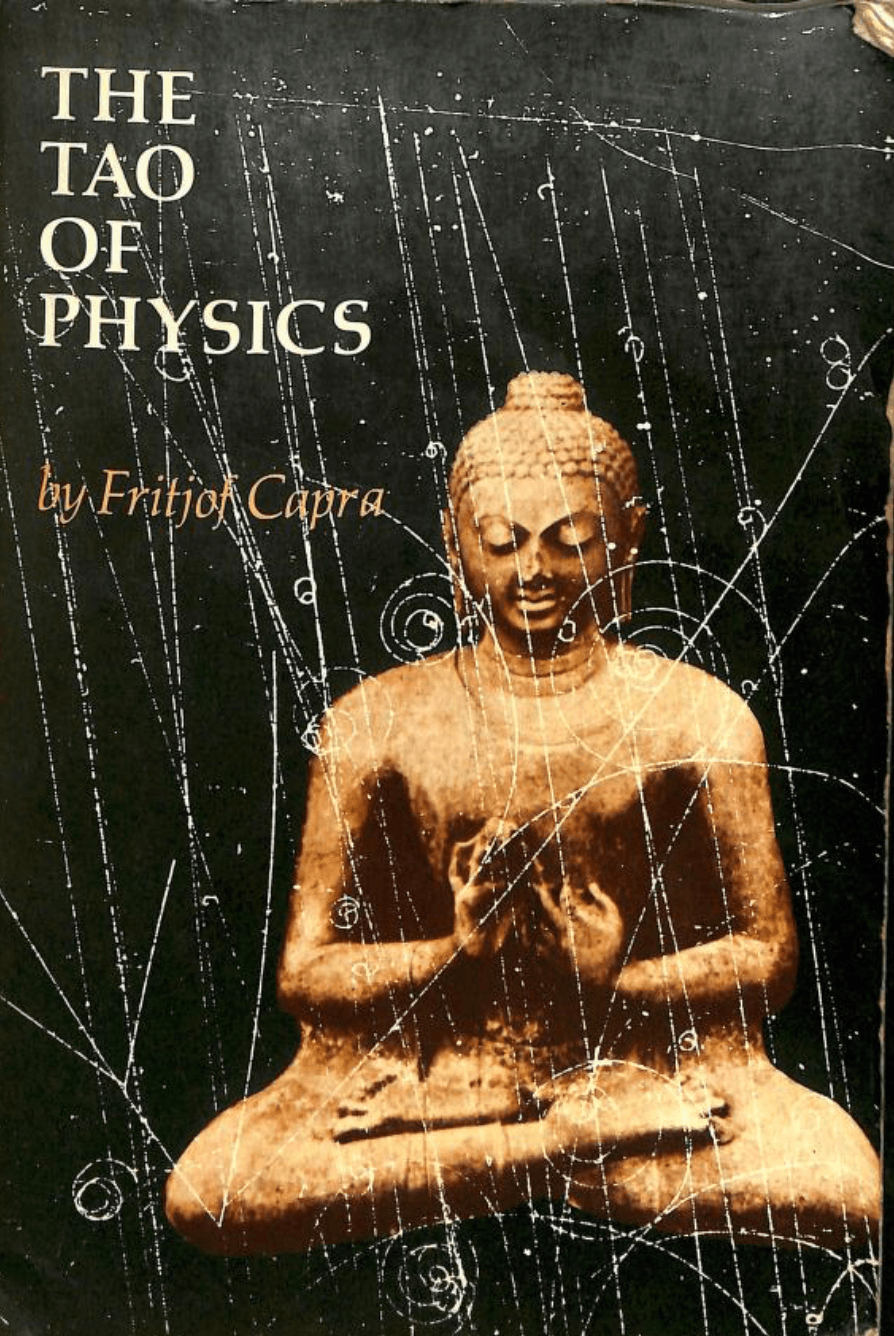

While Wilber built inner models, Fritjof Capra turned outward to the structure of the universe itself. In The Tao of Physics (1975), Capra proposed that modern physics and Eastern mysticism are not so far apart. Quantum theory, with its paradoxes and relational dynamics, seemed to echo ancient Taoist and Buddhist insights about interdependence and impermanence. Reality, Capra suggested, is not made of things, but of relationships. The universe is not a machine, but a network.

Capra’s systems thinking continued in The Web of Life and other works that explored how biological, ecological, and social systems all exhibit properties of self-organization and mutual causality. Though he avoided overt mysticism, Capra’s worldview was fundamentally holistic. He made a compelling case that science, at its best, reveals the same truth mystics have intuited for centuries: that everything is connected, and consciousness may not be an epiphenomenon, but an intrinsic property of complex systems.

Bernardo Kastrup: Consciousness as Fundamental

In recent years, the philosophical landscape has seen a surge of interest in idealism and panpsychism, led by figures like Bernardo Kastrup. A computer scientist and former CERN researcher turned metaphysical philosopher, Kastrup argues that consciousness is the ontological primitive—the ground of all being. In books like The Idea of the World and Dreamed Up Reality, he challenges physicalism with razor-sharp logic and a deep familiarity with both science and mysticism.

Kastrup’s philosophy proposes that what we call the physical world is the extrinsic appearance of deeper mental processes. We, as individuals, are dissociated alters of a universal consciousness—akin to dream characters in a single dreaming mind. His views align with both Eastern nonduality and certain interpretations of quantum mechanics.

In recent years, the philosophical landscape has seen a quiet but profound shift. As materialist explanations of consciousness continue to reach explanatory limits, thinkers like Bernardo Kastrup have reignited interest in idealism—specifically the view that consciousness is not a product of matter, but the fundamental essence of reality itself.

Kastrup, a computer scientist and former researcher at CERN turned philosopher of mind, brings both scientific literacy and metaphysical depth to his argument. In books such as The Idea of the World and Dreamed Up Reality, he lays out a carefully reasoned case for analytic idealism: the notion that the universe is essentially mental, and what we perceive as the physical world is the extrinsic appearance of inner, conscious processes.

He draws striking parallels to Advaita Vedanta, the ancient Indian school of nondual philosophy, which holds that Atman(the individual self) is identical to Brahman (the ultimate, universal consciousness). According to Advaita, the world of forms and separations is maya—an illusion—and the only enduring truth is consciousness itself, infinite and indivisible. Kastrup’s philosophy is not a rehashing of Vedanta, but a modern metaphysical framework that echoes its core: we are dream-like dissociations of a single cosmic mind, and the world we see is its self-reflection.

Importantly, Kastrup does not rely on spiritual revelation to make his case. He uses logic, philosophy of mind, and even interpretations of quantum mechanics to show that idealism offers a simpler, more coherent account of consciousness than reductive physicalism. In doing so, he opens a space for rethinking the nature of reality—one that does not negate science, but invites it into a deeper and more inclusive dialogue with ancient wisdom.

For Kastrup, as for Advaita Vedanta, the journey toward understanding consciousness is not just a theoretical endeavor—it’s a transformation of perception. To recognize that everything arises within consciousness is to dissolve the illusion of separation, and perhaps, to touch the very essence of cosmic consciousness itself.

A New Cosmos of Mind

From James to Goff, from mystical glimpses to integral maps, the journey of cosmic consciousness reflects a deeper human impulse: to understand ourselves as part of something greater, not in abstraction, but in lived, felt, meaningful experience. Across disciplines and decades, the line that connects these thinkers is neither dogma nor doctrine, but the courage to think beyond the visible, and to honor consciousness not as illusion, but as essence.

In the end, cosmic consciousness is not merely a hypothesis—it is a lived possibility, a moment of awakening in which the veil lifts and the self dissolves, not into nothing, but into everything.

previous

Elder Voices of the Millennium: Rupert Sheldrake

next

Feel Good Books: Your Guide to Uplifting Literature That Transforms Lives

Share this

Maria Fonseca

Maria Fonseca is an interdisciplinary educator, writer, artist and researcher whose work bridges the realms of academic knowledge, community engagement, and spiritual inquiry. With a background in Fine Art and a doctorate in creative practice, Maria has spent over a decade exploring the intersections of human experience, cultural meaning, and collective transformation.