Minimalist Masters: How Artists Created Simple and Yet Deeply Meaningful Paintings

Maria Fonseca

Fri Jul 04 2025

This article delves into the work of artists who pioneered minimalist or proto-minimalist styles while deeply rooting their practice in spiritual insight, sacred geometry, and cosmic symbolism. Featuring figures such as Hilma af Klint, Kazimir Malevich, Agnes Martin, Paul Klee, and František Kupka, it explores how simplicity became a pathway to the invisible—revealing how these painters used reduced forms to express profound metaphysical and esoteric truths.

In an age of visual overload, there is something radical about simplicity. Minimalist art, often dismissed as cold or overly intellectual, in fact contains a hidden spiritual and symbolic richness. Beneath the surface of sparse forms and quiet color fields lies a search for truth, for transcendence, and for an experience of presence that words cannot reach.

This article explores five artists who mastered minimalist or proto-minimalist forms while grounding their work in spiritual experience, cosmic symbolism, and sacred geometry. These artists did not just paint less—they painted deeper. They reduced the visible in order to reveal the invisible.

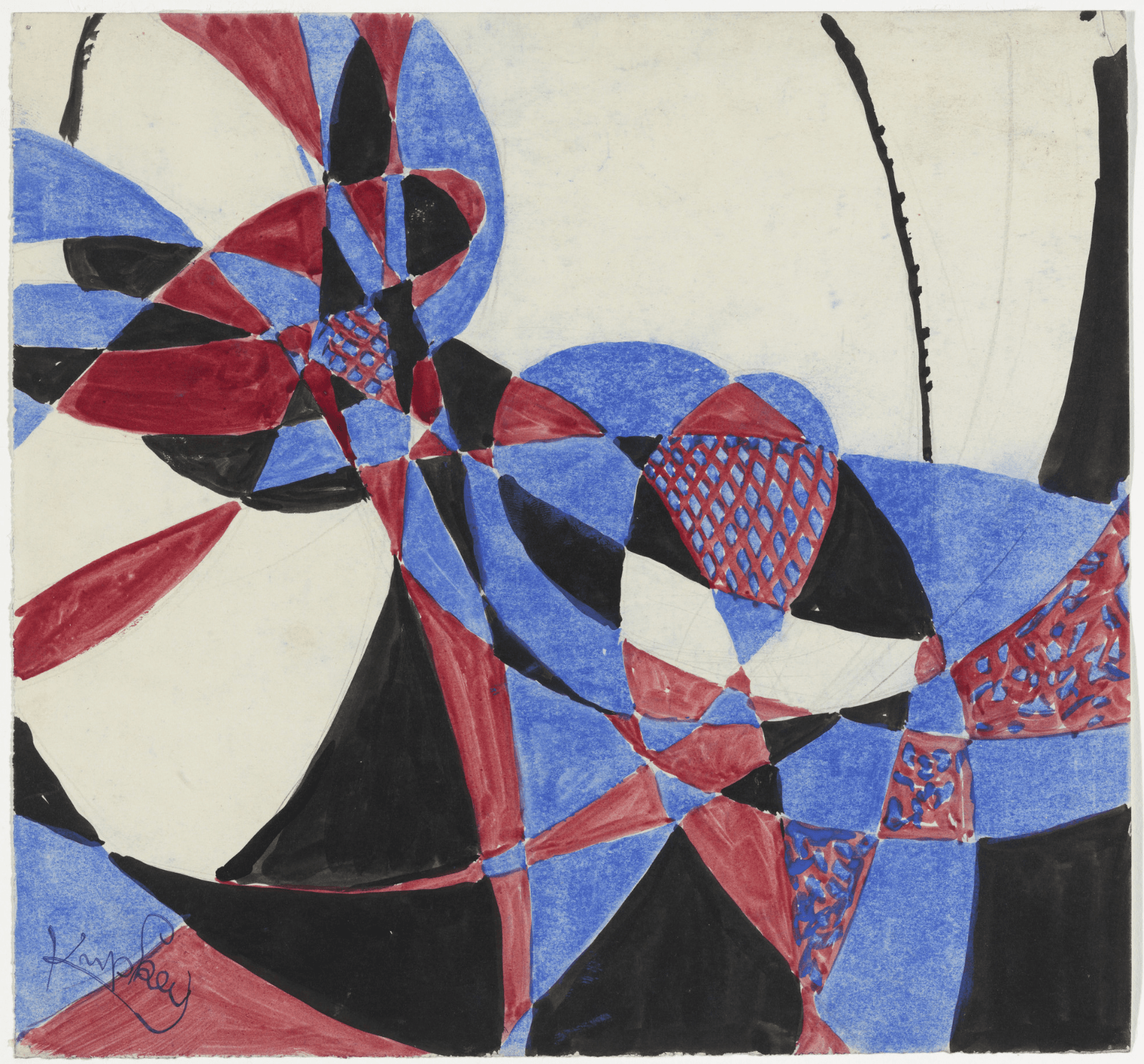

1. František Kupka: Painting the Invisible Forces

František Kupka (1871–1957), a Czech-born artist, was one of the earliest pioneers of abstract art. He began his career in the symbolist tradition, exploring esoteric and philosophical themes. Deeply influenced by Theosophy and Eastern mysticism, Kupka believed that painting could depict the vibrational structures of reality—the hidden forces behind appearances.

In works like Amorpha: Fugue in Two Colors (1912), Kupka created a synesthetic visual field that resembled both music and physics. His circular and flowing forms suggest movement, time, and universal rhythm. For Kupka, abstract art was not random experimentation; it was a form of spiritual science, using visual language to express truths that rational discourse could not.

His journey from figurative symbolism to color-based abstraction was a form of ascension—from outer appearance to inner essence.

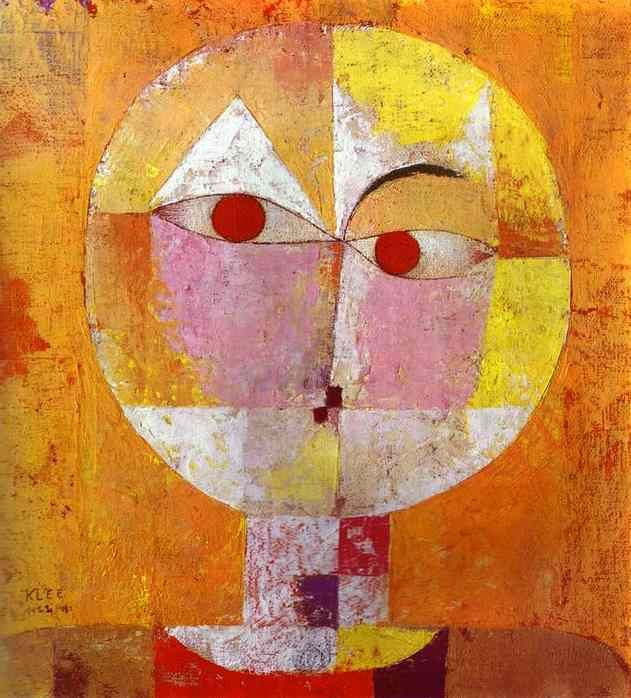

2. Paul Klee: The Playful Architect of Symbols

Paul Klee (1879–1940) merged the analytical clarity of the Bauhaus with mystical intuition. A student of nature, music, and esotericism, Klee saw in minimal forms a key to metaphysical insight. His art often resembles dream diagrams, children's drawings, or mystical maps.

Klee famously said, “Art does not reproduce the visible; it makes visible.” He was interested in the processes behind appearance—growth, rhythm, breath. In paintings like Senecio or Ad Parnassum, he employed simple lines, grids, and geometric shapes not as decoration, but as a kind of spiritual alphabet.

He drew inspiration from Egyptian hieroglyphs, astrology, and Goethe’s color theory. His notebooks reveal a lifelong effort to build a bridge between artistic creativity and cosmic order—a dance between the spontaneous and the structured.

Klee shows us that simplicity can be playful, profound, and poetic all at once.

3. Kazimir Malevich: The Black Square and the Birth of the Void

Kazimir Malevich (1879–1935) is best known for his stark, uncompromising Black Square (1915)—a work that shocked audiences by appearing as a sacred icon of pure feeling. For Malevich, the Black Square was not the end of art, but its rebirth. He called his new movement Suprematism—an art concerned with “the supremacy of pure feeling in creative art.”

Black Square is not simply a minimalist image. It is a metaphysical threshold—a kind of spiritual zero-point. Malevich described it as “the face of the new art.” His purpose with this and posterior paintings, was to create art that all could understand and that would have an emotional impact comparable to religious works.He even placed it in the traditional ‘icon corner’ during exhibitions, where Russian Orthodox icons would usually sit.

Later works introduced floating geometric forms—crosses, circles, rectangles—hovering on white space. These compositions reflect Malevich’s interest in the cosmos, fourth-dimensional space, and spiritual renewal after the collapse of materialist thinking.

Malevich’s minimalism is a radical mysticism: a path to transcend ego, dissolve illusion, and encounter raw awareness.

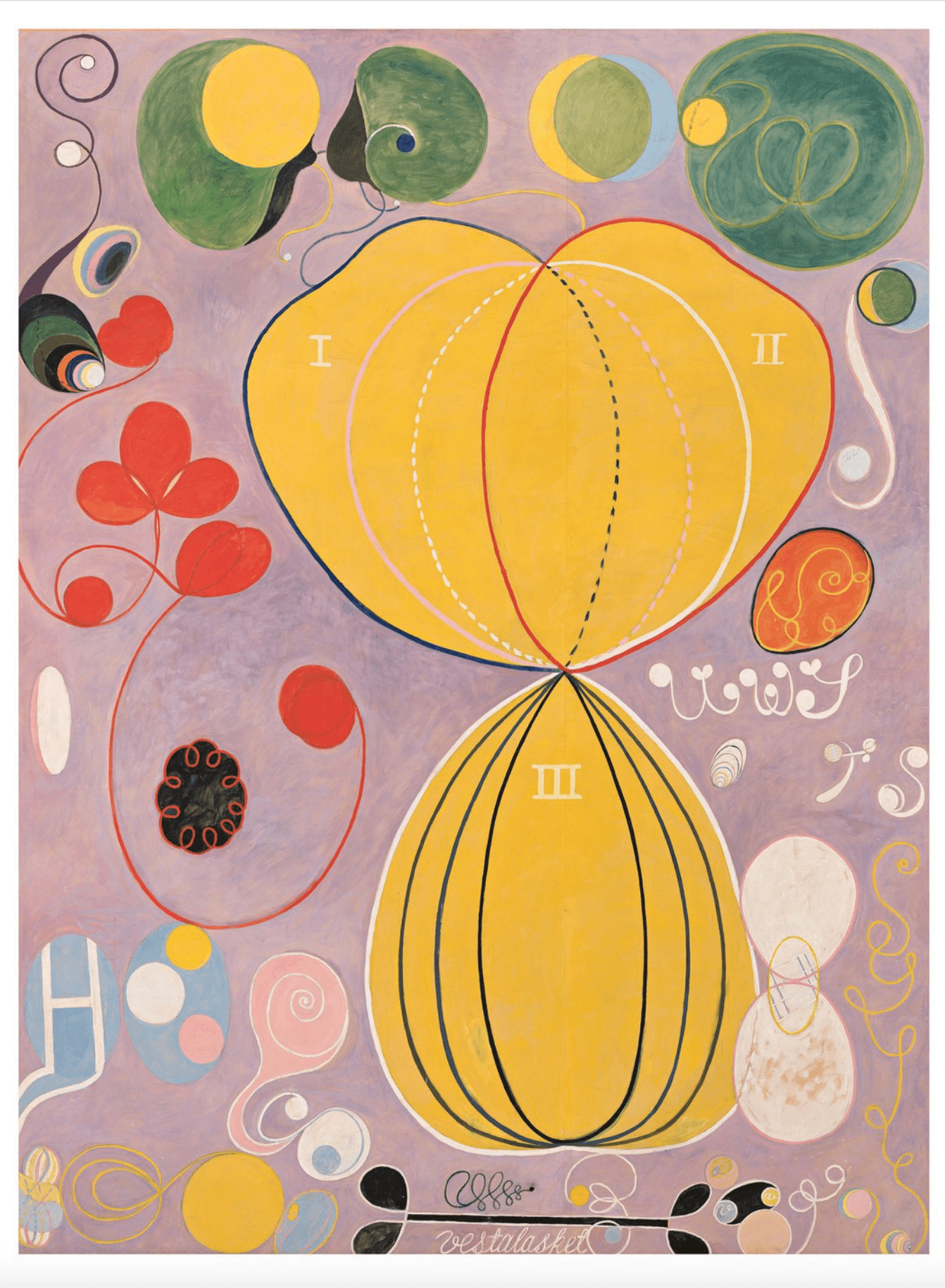

4. Hilma af Klint: The Lost Mystic of Sacred Geometry

Long hidden from art history, Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) is now recognized as one of the true pioneers of abstraction. A Swedish artist and spiritual medium, af Klint began creating abstract works as early as 1906—years before Kandinsky or Mondrian.

Af Klint’s paintings were guided by spiritual beings she referred to as “The High Ones,” and her art aimed to depict multi-dimensional realities, the evolution of consciousness, and the spiritual structure of the cosmos.

Her Paintings for the Temple series, especially The Ten Largest, are vast, symbolic works using spirals, floral motifs, and mandalas. Her art employed sacred geometry as a language of spiritual becoming—depicting cycles of life, polarities, and the divine feminine.

Af Klint did not exhibit much of this work during her life, believing the world was not yet ready. In her case, minimalist abstraction was a sacred transmission—a future message encoded in simplicity.

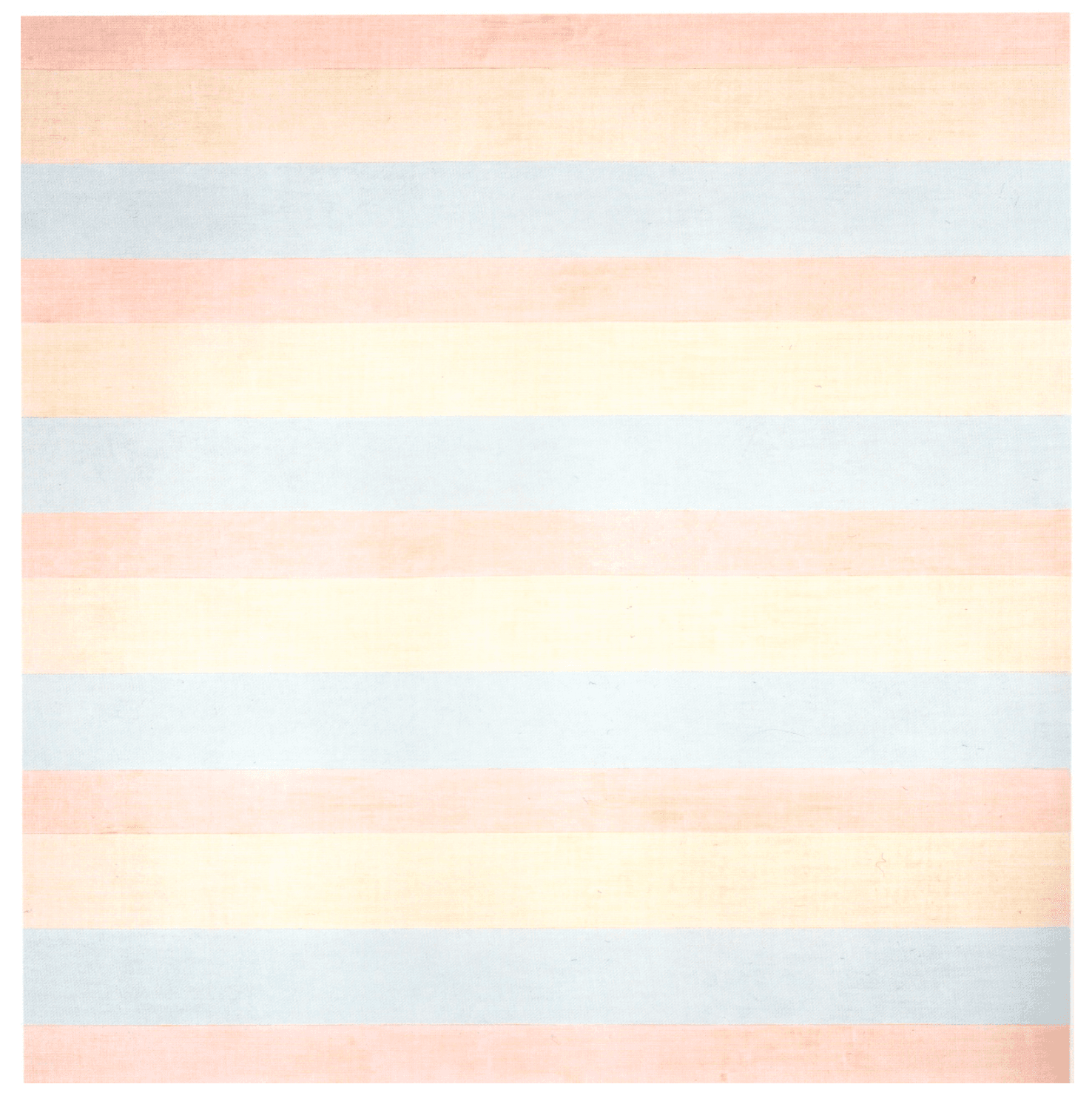

5. Agnes Martin: The Silence of the Grid

Agnes Martin (1912–2004), a Canadian-born painter who lived much of her life in solitude in the deserts of New Mexico, brought an almost monastic depth to minimalist painting. Her signature works consist of faint grids, pale color washes, and hand-drawn lines so subtle they almost disappear into the canvas.

For Martin, painting was not about ideas or theories—it was about states of mind: stillness, love, joy, and innocence. Her minimalist approach was a form of contemplative practice, influenced by Taoism, Zen Buddhism, and her own meditative silence.

“Art is the concrete representation of our most subtle feelings,” she said.

In works like Untitled #10 (1975), horizontal bands in soft pencil barely touch the surface—yet they carry the quiet power of spiritual discipline. Martin used repetition, space, and imperfection as tools for inner alignment. Each painting is a breath, a mantra, a doorway to stillness.

Minimalism as Inner Alchemy ?

What unites these artists is not just aesthetic reduction but a metaphysical ambition. Their works suggest that simplicity is not a lack, but a condensation—a focus of energy. Through sacred geometry, musical structure, cosmic rhythm, or meditative emptiness, these painters used the bare minimum to point toward the infinite.

Many of these artists were influenced—either directly or indirectly—by the spiritual movements of their time: Theosophy, Anthroposophy (Rudolf Steiner), and Eastern philosophies. For instance, Steiner’s work on color, form, and consciousness parallels the pursuits of af Klint and Kupka. His “Philosophy of Freedom” posits that true freedom is achieved not by impulsive desire, but by conscious spiritual thinking—a message echoed in the deliberate restraint of minimalist painters. Klee’s whimsical diagrams express the unseen energies of life and Malevich’s geometric mysticism paved the way for non-objective art to function as a spiritual iconography.

Finally, Agnes Martin’s work, while formally minimal, is emotionally vast. The moving documentary about her life—filmed over four years from 1998 through 2002, during Martin’s ninetieth year—offers a rare, intimate glimpse into her world. It interweaves interviews with Martin, scenes of her working quietly in her Taos, New Mexico studio, archival footage, and images of her art spanning over five decades. The film serves as a unique platform for Martin to reflect on her work, creative process, and life as an artist. She also discusses her film Gabriel and shares readings of her poetry and lectures. True to her chosen life of solitude, Martin is the sole on-screen presence throughout the documentary, emphasising her introspective and contemplative nature.

All of these artists work with shapes, lines, and simple grids inspired by sacred geometry—the notion that certain shapes and proportions carry sacred resonance. When actively engaging with sacred geometry as inspiration for producing creative work, artists enter a process of inner alchemy. This concept is central to several of the artists discussed here. Hilma af Klint’s mandalas and spirals are consciously embedded in esoteric traditions, while Kupka drew inspiration from harmonic ratios and cosmic cycles. Agnes Martin’s life in solitude was inspired by Zen Buddhism.

These shapes were not merely formal devices; they were symbols of inner states, universal principles, and the architecture of consciousness. As Rudolf Steiner said, “In the geometrical, we find the divine made manifest in form.”

Minimalism, then, can be seen as a return to the archetypal—the eternal, timeless language that predates image and culture.

Simplicity as a Spiritual Practice

Minimalist art teaches us something important: when we reduce external noise, we gain access to inner clarity. When we strip away narrative and representation, we can meet reality more directly—not through explanation, but through experience.

In a world of distraction and complexity, the silent intensity of minimalist work calls us to presence. It suggests that simplicity is not emptiness—it is depth.

These artists remind us that art can be more than visual. It can be meditative. It can be healing. It can be a form of wisdom.

previous

Are Crows Smart? The Remarkable Intelligence That Might Change How You See the World

next

How Unity in Art Creates Visual Comfort and Balance

Share this

Maria Fonseca

Maria Fonseca is an interdisciplinary educator, writer, artist and researcher whose work bridges the realms of academic knowledge, community engagement, and spiritual inquiry. With a background in Fine Art and a doctorate in creative practice, Maria has spent over a decade exploring the intersections of human experience, cultural meaning, and collective transformation.

More Articles

World Labs: What Fei-Fei Li's Spatial Intelligence Platforms Means for the Future of AI

Are the Laws of the Universe Discovered or Imposed?

Chinese New Year 2026: Galloping Into the Year of the Fire Horse

The Machiavellian Principles Applied In An AI Hallucination Time (Part 5)

The Machiavellian Principles Applied In An AI Hallucination Time (Part 4)