Game-Based Learning in Education: From Froebel to Classcraft ?

Maria Fonseca

Tue Jun 10 2025

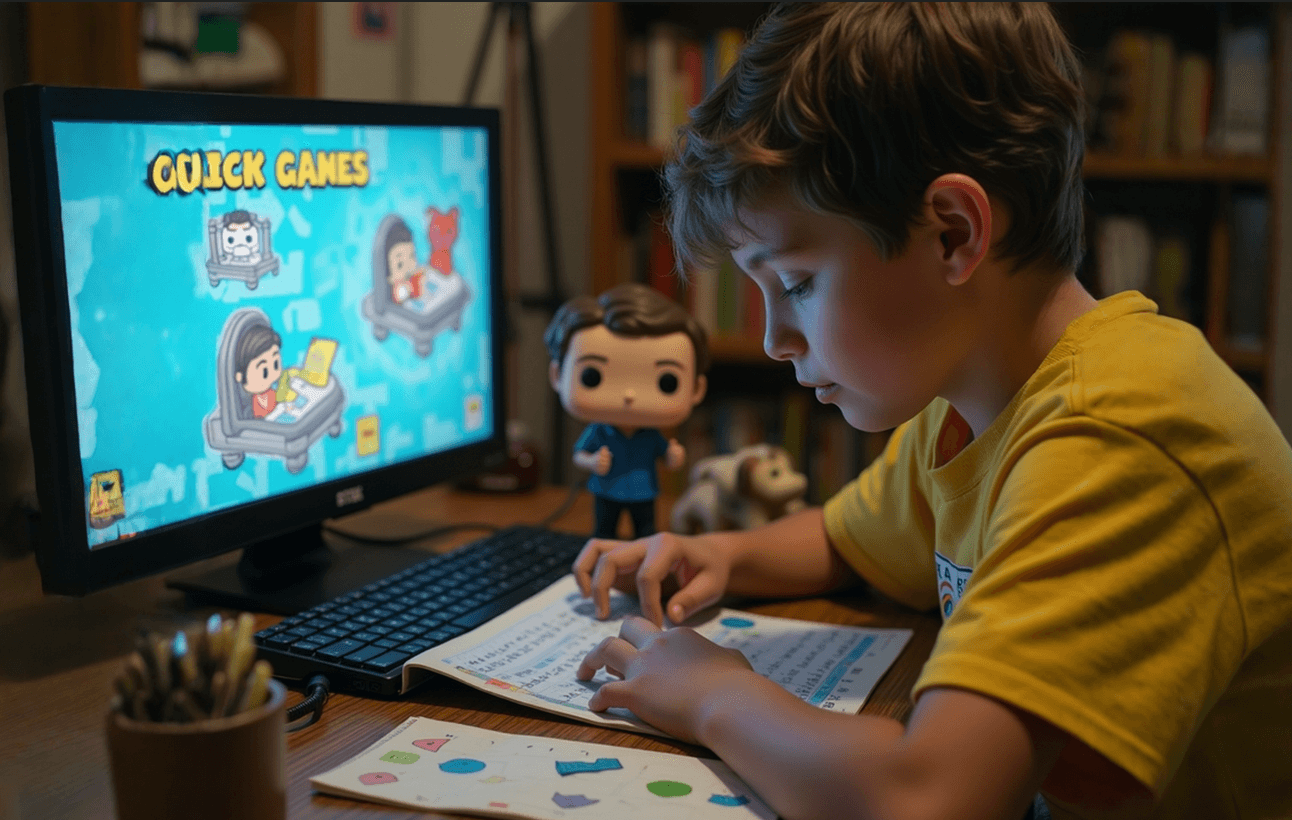

Humans have loved games since the dawn of history. Through games we engage with each other, we play, we learn. Whether etched into the sand with a stick or coded into a screen, games have always held a unique power to draw us in. They mirror life’s challenges in miniature, give us goals to strive for, rules to follow, feedback to respond to, and the satisfaction of growth and mastery. But what happens when we bring games not only into our lives but into our classrooms? Today, the transformative world of game-based learning (GBL) is revolutionizing classrooms worldwide—but is it truly a realm where curiosity, creativity, and challenge collide to bring learning to life, or is it just a passing fad? And what is the real power of play and games in education?

The Roots: Friedrich Froebel and the Kindergarten Movement

Long before the first digital device, a 19th-century German educator named Friedrich Froebel laid the philosophical foundation for playful learning. Froebel invented the concept of the kindergarten, or “children’s garden,” a space where structured play was seen not as a distraction from learning, but as its very essence.

Froebel believed that play was the highest expression of human development in childhood—essential for fostering creativity, autonomy, and understanding. His approach blended songs, stories, crafts, and educational toys (known as "Froebel Gifts") to stimulate learning through activity and discovery. These ideas weren’t just innovative; they were revolutionary.

This philosophy—that play could be purpose-driven—remains a guiding light for today’s game-based learning advocates. While Froebel used wooden blocks and songs, modern educators have digital worlds and multiplayer platforms at their fingertips.

The Digital Turn: When Play Meets Technology

The leap from toy blocks to touchscreens took time, but the seeds were sown with the rise of educational video games in the 1970s and 80s. One of the earliest successes was "The Oregon Trail," a game developed to teach American history through the lens of survival on the western frontier. Players had to make real decisions—what supplies to buy, whether to ford a river or wait—all of which affected the outcome. It was simple, yet profoundly immersive.

Games like “Math Blaster,” “Reader Rabbit,” and “Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego?” followed, blending storytelling with subject-based content. These titles didn’t just teach; they sparked excitement, triggered problem-solving, and made kids want to keep playing—and thus, learning.

As technology evolved, so did the complexity and potential of educational games. The 2000s saw a proliferation of platforms like Minecraft: Education Edition, Kahoot!, and Duolingo, all integrating elements of competition, exploration, and rewards to boost engagement and retention.

What Exactly Is Game-Based Learning?

At its heart, game-based learning (GBL) is the use of games to achieve learning objectives. This can range from simple quiz games to immersive role-playing environments that simulate real-world challenges.

What sets GBL apart from traditional educational methods is its interactivity and agency. Rather than being passive recipients of information, students become active participants. They make choices, face consequences, and often collaborate with others to achieve goals. Whether battling dragons or solving algebra puzzles, they’re engaged on cognitive, emotional, and social levels.

Research supports its effectiveness. According to a study cited in Paper's blog on game-based learning, games promote problem-solving skills, critical thinking, motivation, and memory retention. And crucially, they can offer a safe space to fail—something traditional classrooms often struggle to provide.

Gamification vs. Game-Based Learning

It’s important to distinguish between gamification and game-based learning. While both draw from game principles, they are not the same.

Gamification refers to adding game-like elements—points, badges, leaderboards—to traditional tasks to make them more engaging. Think of turning a reading assignment into a quest with rewards.

Game-based learning, on the other hand, uses actual games as the central mode of instruction. The game itself isthe learning experience.

While both strategies have merit, GBL often goes deeper in creating authentic, immersive learning environments that promote creativity, collaboration, and intrinsic motivation.

The Psychology Behind the Power of Play

What makes games such powerful learning tools? Educational theorists and psychologists offer several insights:

Flow and Motivation

Psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi introduced the concept of “flow”—the mental state of being completely absorbed in an activity.

In Csikszentmihalyi seminal book Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience he explained how:

“The best moments in our lives are not the passive, receptive, relaxing times... The best moments usually occur when a person’s body or mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile.”

This beautifully captures the essence of flow—a state of deep focus, joy, and engagement that often emerges during meaningful play or learning.Well-designed games trigger this state, balancing challenge and skill to keep players “in the zone.” When learners are in flow, they’re more likely to persist, solve problems, and absorb content.

Csikszentmihalyi would further write that: “The idea is not to control the student, but to help him or her to enjoy the process of learning, to find flow in it, and thereby become intrinsically motivated.”

Narrative and Identity

Many games use storytelling and role-playing, allowing learners to assume identities and make meaningful choices. In a historical simulation, students can experience the life of a Renaissance artist or a civil rights activist. This kind of empathic engagement deepens understanding and emotional connection to the material.

Instant Feedback and Mastery

Unlike most school tasks, games give immediate feedback. Missed a step? Try again. Want to level up? Improve your strategy. This loop of feedback and revision is essential for mastery learning, where students progress at their own pace and gain confidence with each success.

Collaboration and Competition

Multiplayer games foster teamwork and communication—essential skills for the 21st century. They create dynamic spaces where young learners can co-create, negotiate, and problem-solve together. Imagine two children, Maya and Zane, working together in a game like Minecraft Education Edition. Their goal? To build a sustainable city from scratch.

Maya sketches out energy grids powered by wind turbines, while Zane constructs eco-friendly homes with recycled materials. They debate zoning laws, plan public transport routes, and even simulate natural disasters to test the city’s resilience. Sometimes they disagree, but that only sharpens their communication and decision-making skills.

Then comes a twist: they're competing against another team to see whose city will earn the highest livability score. The friendly competition heightens their focus and motivates them to improve their project. Here, collaboration and competition don’t cancel each other out—they enrich the learning process, blending teamwork with the thrill of a shared challenge.

This balance of cooperative creativity and healthy rivalry helps children not only understand complex systems but also develop empathy, adaptability, and a growth mindset.

Real Classrooms, Real Impact

Across the world, teachers are using GBL to bring learning to life:

In a primary school in the Midlands, UK, the usual hum of the morning register is replaced by the excitement of a digital quest. Each student logs into Classcraft, a fantasy-based learning management system where every good decision—whether it’s helping a classmate or handing in homework on time—translates into rewards for their in-game character. Instead of the old sticker charts or detentions, students become mages, warriors, or healers, working together in teams to earn points and unlock adventures. Even the most reluctant learners begin to engage, driven not just by competition, but by a shared story.

One teacher, Mrs. Patel, shares how she uses Classcraft to turn classroom behaviour into meaningful narrative. When a student forgets their book, their team loses health points; when someone demonstrates kindness or creativity, they unlock magical items or special powers. The classroom feels less like a series of rules to follow and more like a world to explore. Discipline becomes immersive, not punitive. For students, the boundaries between learning and play begin to blur—and that’s where the magic happens.

A similar scenario happens in other parts of the world. In the U.S., SimCityEdu lets students design sustainable cities, grappling with trade-offs in economics, energy, and public policy. In Finland, a country known for educational innovation, schools use Minecraft to teach architecture, environmental science, and history.

Addressing the Critics

Of course, not everyone is sold. Some worry that games are a distraction, or that they may oversimplify complex topics. Others fear that digital GBL promotes screen time at the expense of deeper reflection.

These concerns are valid—but they depend largely on how games are used. Game-based learning should never replace sound pedagogy. It should complement it. The best educational games are aligned with clear learning outcomes, culturally responsive, and inclusive. They are scaffolded by thoughtful teaching, and they invite students not just to play, but to reflect on what they’ve learned.

Equity and Access

Another critical consideration is access. Not all students have equal access to devices, high-speed internet, or gaming platforms. If not addressed, GBL could widen the digital divide.

To ensure equity, schools and policymakers must invest in infrastructure, training, and inclusive design. Many GBL platforms are now moving toward low-bandwidth, browser-based tools, and offering free teacher training. Open-source platforms and non-profit initiatives are also helping to level the playing field.

The Future of Game-Based Learning

As we look ahead, the potential of GBL is expanding in exciting ways:

Virtual and Augmented Reality can transport students into ancient civilizations, outer space, or inside the human body.

AI-driven adaptive learning can tailor game difficulty and content to individual student needs.

Blockchain and tokenization may soon create verifiable learning achievements tied to gameplay and skill-building.

Experiential, scenario-based simulations are being used not only in schools but in professional training—medical, military, and corporate.

Yet even as technology advances, the core principle remains the same: play is a powerful pathway to learning.

Rediscovering the Joy of Learning

Friedrich Froebel believed that children should be free to explore, imagine, and build. Today’s game-based learning continues that vision, inviting learners into worlds where education is not something done to them, but something they actively shape and experience.

In a time when many students feel disillusioned with rote memorization and standardized tests, GBL offers an antidote—a way to rekindle curiosity, joy, and agency. It reminds us that to play is to learn, and that through games, we can craft more human, meaningful, and lasting educational experiences.

In the words of educator Seymour Papert, one of the pioneers of learning through technology:

“The role of the teacher is to create the conditions for invention rather than provide ready-made knowledge.”

Game-based learning does exactly that—and the game is just getting started.

previous

Underwater Waterfall: Mauritius’ Impossible Wonder of Nature

next

Who Are You As a Writer? A Journey of Discovery

Share this

Maria Fonseca

Maria Fonseca is an interdisciplinary educator, writer, artist and researcher whose work bridges the realms of academic knowledge, community engagement, and spiritual inquiry. With a background in Fine Art and a doctorate in creative practice, Maria has spent over a decade exploring the intersections of human experience, cultural meaning, and collective transformation.