Renaissance Humanism and the Birth of the Modern Gaze: Images That Taught Us to See Ourselves

Dinis GuardaAuthor

Tue Dec 16 2025

Explore how 25 transformative images, from Giotto and Leonardo to Goya and early photography, shifted humanity from divine authority to human agency, reshaping modern consciousness, identity, and the ethics of seeing.

From Divine Authority to Human Agency: The Visual Revolution That Created Modernity

From “ The most Influential Powerful 100 Images in History of Humanity” mini-book By Dinis Guarda

The Moment Humanity Looked in the Mirror

Between 1400 and 1900, something extraordinary happened to human vision. We stopped looking primarily upward toward gods and began looking outward toward each other, and inward toward ourselves.

The Renaissance didn't just revive classical learning; it fundamentally transformed how humans understood representation itself. For the first time since antiquity, artists signed their names. Individuals became worthy subjects. The human body, naked, sensual, particular, returned to canvas and marble not as sin but as celebration.

Then came an invention that would change everything: photography. In 1839, reality became mechanically reproducible. Memory could be preserved without human hand, without artistic interpretation. Or so we thought. Photography proved to be the most seductive lie—appearing objective while constructing reality as surely as any painter's brush.

This second installment of our visual journey explores 25 images that bridge the gap between medieval faith and modern consciousness. We begin with Renaissance masters rediscovering human dignity, move through Baroque drama that made light itself theological, witness Enlightenment revolutions that weaponized images, and arrive at photography's birth, the moment when machines learned to see.

These images taught us to see ourselves. Not as God's subjects or empire's servants, but as individuals worthy of attention, contemplation, and immortality. They democratized representation, made the secular sacred, and ultimately gave us the visual language we still use to understand what it means to be human.

The transformation happens in stages: first, oil paint allows unprecedented realism (van Eyck). Then, classical bodies return without shame (Botticelli). Linear perspective mathematizes space (Leonardo, Raphael). Chiaroscuro makes light dramatic (Caravaggio). Finally, the camera arrives, and suddenly everyone, not just the powerful, can be immortalized.

By 1900, the visual landscape has been completely remade. Images no longer belong exclusively to churches, palaces, and the wealthy. Photography has begun its march toward universal accessibility. The 20th century's visual explosions, cinema, television, digital imagery, become possible only because these 25 images first taught us that representation itself could be democratized, questioned, and reimagined.

We continue our journey where the first 25 images left us: at the threshold of the Renaissance, where humanity was about to rediscover its own face.

RENAISSANCE HUMANISM: When Humanity Gazed Upon Itself (1400-1600)

26. Giotto's "Lamentation of Christ" (Scrovegni Chapel) (1305)

Location: Scrovegni Chapel, Padua, Italy

Medium: Fresco

The dead Christ lies diagonally across the composition while Mary cradles his head, a scene rendered with such human grief that it shattered Byzantine conventions. Giotto introduced weight, volume, emotion. The mourners don't pose; they weep.

Angels thrash in the sky, their anguish matching the humans below. This image didn't illustrate the Gospel, it made viewers feel it. Giotto broke the medieval visual code, inaugurating Renaissance naturalism three centuries early.

Before Giotto, religious figures floated in gold-leaf eternity, hieratic and distant. Giotto placed them on earth, gave them mass and gravity, made them bleed and mourn like actual humans. The chapel's walls tell Christ's story and Mary's life in continuous narrative, medieval comic strip meets proto-Renaissance psychology.

The diagonal composition creates unstoppable momentum toward Christ's body. Mary's face, devastated, disbelieving, captures grief's paralysis. John throws his arms back in despair. Mary Magdalene cradles Christ's feet. These aren't symbols; they're people experiencing the worst moment of their lives.

Giotto painted this between 1303-1305 for Enrico Scrovegni, a wealthy Paduan whose father was so notorious as a usurer that Dante placed him in Hell. The chapel was Enrico's attempted spiritual redemption, guilt transformed into beauty, sin laundered through art. The irony: this monument to Christian piety was funded by the period's equivalent of predatory lending.

27. Jan van Eyck - "The Arnolfini Portrait" (1434)

Location: National Gallery, London

Medium: Oil on oak panel (82.2 × 60 cm)

Giovanni Arnolfini and his wife stand in a Flemish interior. Every surface, the convex mirror, the chandelier, the oranges, the dog, is rendered with obsessive precision. On the wall, van Eyck signs: “Jan van Eyck was here, 1434”, transforming the painting into witness to a marriage contract.

The mirror reflects the couple from behind and two figures in the doorway (one presumably van Eyck). This is the first selfie, the first self-aware meta-image in Western art.

Van Eyck's mastery of oil paint allowed unprecedented detail. You can see individual carpet fibers, the fur trim on clothing, light refracting through the chandelier's glass. This isn't symbolic medieval art—it's documentary realism that makes the 15th century feel present tense.

But symbolism persists: the single candle (Christ's presence), the dog (fidelity), the oranges (wealth and fertility), the discarded shoes (holy ground). Van Eyck operates in both registers, medieval symbol-maker and Renaissance realist, creating an image that works as religious icon and legal document simultaneously.

The mirror is key. It reveals what the painting's frontal view hides: the room's other half, the witnesses, the artist himself. Van Eyck announces: I was present. I saw this. The painting is evidence, notarized by artistic signature. This is modernity's birth certificate, the artist as individual authority, not anonymous craftsman.

28. Botticelli - "The Birth of Venus" (c. 1485)

Location: Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Medium: Tempera on canvas (172.5 × 278.9 cm)

Venus rises from the sea on a shell, blown by Zephyrs while a nymph offers her a cloak. The first large-scale nude goddess since antiquity, painted for the Medici. Her contrapposto echoes classical sculpture; her modesty is unconvincing.

This image declares: pagan beauty is permissible again. The Renaissance's permission to desire, rendered in tempera.

For a millennium, the naked body had been Christianity's shameful problem, evidence of the Fall, temptation incarnate. Botticelli, painting for sophisticated Medici patrons, resurrects classical mythology's celebration of beauty. Venus isn't Christian virtue personified; she's literally the goddess of love and sexuality.

Yet there's ambiguity. Venus's pose (one hand covering her breast, the other her genitals) is called the “Venus pudica”, the modest Venus. Is this shame or invitation? Is Botticelli celebrating or containing female sexuality? The image has generated feminist debates for decades.

The composition flows like a dream: Zephyrs (west wind gods) blow Venus to shore, their bodies intertwined. The nymph (possibly one of the Horae, goddesses of seasons) rushes to clothe her. Venus herself seems almost surprised by her own existence, as if beauty this profound bewilders even its embodiment.

Botticelli worked for the Medici, Florence's de facto rulers who commissioned art celebrating humanism, classical learning, and, not coincidentally, their own sophistication. This painting announces: we're educated enough to appreciate pagan gods, wealthy enough to commission masterpieces, secure enough in our Christianity to enjoy naked goddesses.

29. Leonardo da Vinci - "The Last Supper" (1495-1498)

Location: Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

Medium: Tempera and oil on plaster (460 × 880 cm)

Christ announces betrayal; the apostles explode into twelve distinct reactions. Leonardo used experimental techniques (mixing oil with tempera on dry plaster) that caused immediate deterioration, the image began flaking before completion.

Restored repeatedly, bombed in WWII (survived miraculously), it endures as Western art's most iconic representation of the moment before sacrifice. Every Hollywood "team sits down for dinner before the heist" shot quotes this composition.

Leonardo's genius was psychological. Each apostle reacts differently to Christ's announcement: Peter (knife in hand) leans aggressively; John slumps; Judas (unusually, included among the twelve rather than isolated) clutches his money bag. Leonardo painted not a frozen devotional image but a moment of dramatic crisis, time captured mid-explosion.

The perspective is mathematically precise, with all lines converging on Christ's head. The windows behind him create a halo effect. Even as apostles gesture frantically, Christ sits calm, hands spread, accepting destiny. The composition's symmetry (six apostles each side) creates balance amid chaos.

The painting's deterioration is tragic irony: Leonardo's experimental technique failed, yet the image became Christianity's most reproduced. We know it mostly through copies, photographs, parodies. The "original" is so damaged and restored that scholars debate how much is Leonardo's hand versus subsequent interventions. The image survives its own material decay.

30. Leonardo da Vinci - "Mona Lisa" (c. 1503-1519)

Location: Louvre Museum, Paris

Medium: Oil on poplar panel (77 × 53 cm)

Lisa Gherardini sits before a desolate landscape, her expression ambiguous, her eyes following viewers around the room (actually an optical illusion created by Leonardo's understanding of peripheral vision).

The most famous painting in existence, protected behind bulletproof glass, seen by 10 million visitors annually. Stolen (1911), recovered, parodied endlessly (Duchamp added mustache), it has transcended art to become pure icon.

Why is the Mona Lisa famous? Not because it's the "best" painting, it's not. It's famous because it's famous, a self-perpetuating feedback loop of cultural attention. But Leonardo's technical mastery deserves recognition: the sfumato (smokiness) technique blurs edges, making the face seem alive. No harsh lines exist, everything transitions gradually, like memory or atmosphere.

The landscape behind her is impossible, the horizons don't match left to right. This isn't realism but dreamscape. Lisa sits between civilization (her clothing, her pose) and wilderness (those strange rock formations). She is threshold between known and unknown.

Her smile, the most analyzed facial expression in art history, is both present and absent. Look directly at her mouth: it's neutral. Look at her eyes: she seems to smile. This ambiguity keeps us looking, trying to decode what cannot be decoded. Leonardo understood that the most powerful images are those that refuse to resolve.

The painting's theft in 1911 by Italian handyman Vincenzo Peruggia (who wanted to "return" it to Italy) made international headlines. When recovered, crowds lined up to see it. The theft transformed it from masterpiece into celebrity. Now it's less a painting than a pilgrimage site, you visit the Mona Lisa like you visit a shrine.

31. Michelangelo - "The Creation of Adam" (Sistine Chapel Ceiling) (1512)

Location: Sistine Chapel, Vatican City

Medium: Fresco

God's finger nearly touches Adam's, the spark of divine life about to transmit. The negative space between their fingers is Western art's most famous gap.

Recent analysis suggests the shapes behind God resemble a human brain (God dwells in the brain; consciousness is divine). Michelangelo painted the Sistine Ceiling standing on scaffolding, paint dripping on his face, for four years. When finished, he'd immortalized humanity's origin myth in a single gesture.

This is the instant before consciousness, the microsecond before Adam becomes fully human. God actively reaches; Adam passively receives. Yet there's a subtle difference: God's arm is extended with effort, moving through space. Adam's arm is languid, barely reaching. The implication: God desires to create more than Adam desires to be created.

The figures' poses mirror each other, God is what Adam will become; Adam is God's reflection. The two hands don't touch (despite popular misremembering), the gap is crucial. Connection is imminent but not complete, potential rather than actual. This is creation as process, not event.

The "brain" theory is compelling: the shape containing God and angels matches anatomical drawings of the human brain, cerebellum, brain stem, and all. Michelangelo studied anatomy by dissecting corpses. Did he intentionally paint God emerging from Adam's mind? The image suggests consciousness creates divinity as surely as divinity creates consciousness.

Michelangelo was 37 when he began the ceiling, painting 12,000 square feet over four years. He wrote a sonnet complaining about the physical toll: "My beard turns up to heaven; my nape falls in... I'm bent as a Syrian bow." Genius emerging from suffering, very Renaissance.

32. Raphael - "The School of Athens" (1509-1511)

Location: Stanza della Segnatura, Apostolic Palace, Vatican City

Medium: Fresco (500 × 770 cm)

This is humanity's mirror, the Renaissance captured in a single image. An imagined assembly of history's greatest philosophers, mathematicians, and scientists gather in a grand architectural space inspired by Bramante's design for St. Peter's Basilica.

At the composition's center: Plato and Aristotle. Plato (modeled on Leonardo da Vinci) points upward toward ideal forms and eternal truths; Aristotle gestures toward the earth, emphasizing empirical observation and material particulars. This single gesture crystallizes Western philosophy's central tension: idealism versus materialism, heaven versus earth, theory versus practice.

The vanishing point lies precisely between them, drawing every viewer's eye to this philosophical dialogue. Surrounding them: Pythagoras demonstrates musical ratios; Euclid (possibly a portrait of Bramante) bends over geometric proofs; Heraclitus (clearly Michelangelo, added later) broods in solitary contemplation; Ptolemy and Zoroaster hold celestial and terrestrial globes. And there, in the lower right, Raphael himself looks directly at us, the artist placing himself within the pantheon of genius.

This is more than a painting. It's visual philosophy, aesthetic theology, psychological architecture. It declares that knowledge, secular and sacred, ancient and modern, mathematical and poetic, forms a unified whole. The Renaissance believed humans could comprehend everything; Raphael proved they could paint everything.

For five centuries, this image has defined what the life of the mind looks like. Every library reading room, every university assembly hall, every vision of intellectual community quotes this composition. When we imagine "the academy," we imagine this.

Inscribed above: "Causarum Cognitio" (Seek Knowledge of Causes). The fresco was painted for Pope Julius II's private library, the room where the most powerful man in Christendom contemplated humanity's accumulated wisdom. That Raphael could integrate pagan philosophers into a papal palace demonstrates the Renaissance's radical synthesis: Christianity and classical learning aren't enemies but partners in understanding reality.

This is humanity at its most optimistic: the belief that reason, beauty, and faith can coexist; that the past illuminates the present; that diverse minds in dialogue create civilization. Standing before it in the Vatican Museums remains one of the great aesthetic experiences available to humans. The image reminds us what we can be when we gather to think rather than conquer, to debate rather than destroy.

33. Hieronymus Bosch - "The Garden of Earthly Delights" (Central Panel) (c. 1490-1510)

Location: Prado Museum, Madrid

Medium: Oil on oak panels (triptych, central panel: 220 × 195 cm)

Paradise (left), earthly pleasures (center), Hell (right). The center panel swarms with nude figures copulating with giant strawberries, entering eggs, riding bizarre hybrid animals, a carnival of desire that's either condemnation or celebration (scholars debate).

This is humanity's unconscious made visible five centuries before Freud.

When closed, the triptych shows Earth during Creation, a grey sphere floating in cosmic darkness. Open it, and color explodes: pink flesh, red fruits, blue pools, golden structures. Paradise on the left shows Adam and Eve at the moment God presents them; Hell on the right features a bird-headed demon consuming souls and defecating them into a pit.

But it's the central panel, the "Garden of Earthly Delights" itself, that mesmerizes and disturbs. Hundreds of naked figures engage in activities simultaneously erotic and absurd: entering giant shells, balancing oversized berries, forming human pyramids, coupling inside transparent spheres. Are they damned? Innocent? Enjoying pre-Fall paradise or post-Fall delusion?

Bosch's creatures are fever-dream amalgamations: fish with legs, birds wearing fruit hats, musical instruments that torture. This is surrealism 400 years before surrealists. The 20th-century avant-garde didn't invent the unconscious made visible, Bosch got there first, armed with medieval symbolism and extraordinary imagination.

The painting's original purpose remains debated. Commission for a private collection? Moral warning? Secret heretical text? The ambiguity is part of its power. Bosch refuses to clarify whether pleasure damns or liberates, whether the body's desires are divine gift or satanic trap.

34. Albrecht Dürer - "Melencolia I" (1514)

Location: Multiple impressions in museums worldwide

Medium: Engraving (24 × 18.8 cm)

A winged figure slumps in depression, surrounded by unused tools, compass, plane, sphere, polyhedron. A magic square (where every row/column/diagonal sums to 34) hangs on the wall. This is genius paralyzed by possibility, creativity frozen by melancholy.

Dürer explored depression centuries before it had clinical definition.

The winged figure represents melancholy, one of the four humors medieval medicine believed governed personality. But Dürer transforms medical theory into psychological portrait. The angel has tools for creation, knowledge for achievement, yet sits paralyzed, head resting on hand in classic melancholic pose.

Everything in the composition symbolizes unrealized potential: geometric solids that could be measured, tools that could build, an hourglass that marks time's passage while nothing is accomplished. Even the dog is listless. This is creative block visualized, the artist's nightmare of having everything needed except will.

The magic square contains a date: 1514, the year Dürer's mother died. The engraving becomes memorial to grief. The bottom row reads “4, 15, 14, 1”, the middle numbers (15, 14) suggest 1514. Grief transforms productivity into paralysis; loss makes creation impossible.

Yet Dürer created this masterpiece depicting creative paralysis, meaning he overcame what he depicted. The engraving itself is evidence that art can emerge from depression. This meta-textual irony makes the image more powerful: it proves that documenting creative block is itself creative act.

35. Pieter Bruegel the Elder - "The Triumph of Death" (c. 1562)

Location: Prado Museum, Madrid

Medium: Oil on panel (117 × 162 cm)

An army of skeletons massacres humanity, kings, peasants, lovers, priests, all equal before death. In the background, the earth burns. Painted during plague outbreaks and religious wars, this is the apocalypse as black comedy. No one escapes; death is democratic.

Bruegel's nightmare is meticulously detailed: skeletons herd humans into a coffin-shaped trap; a skeleton king empties an hourglass; death on horseback tramples victims; lovers embrace while a skeleton plays lute behind them, about to interrupt. Ships sink, cities burn, gallows line horizons.

This isn't Christian Last Judgment with salvation possibility, this is universal slaughter. The painting reflects mid-16th-century anxiety: Protestant Reformation, Catholic Counter-Reformation, plague returning cyclically, wars ravaging Europe. Death is the only certainty; the only democracy is the grave.

Yet there's dark humor: a jester hides under a table, clutching playing cards, entertainment provides no protection. A cardinal dies while a skeleton steals his gold cross, piety provides no immunity. A king's corpse is robbed of crown, power provides no continuity.

The painting influenced 20th-century apocalyptic imagery from Holocaust art to nuclear anxiety to zombie films. Bruegel understood: the most horrific visions gain power through detail. Horror isn't vague, it's specific, individual, inescapable.

BAROQUE DRAMA: When Light Became Theology (1600-1750)

36. Caravaggio - "The Calling of Saint Matthew" (1599-1600)

Location: Contarelli Chapel, San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome

Medium: Oil on canvas (322 × 340 cm)

Christ enters a tavern where tax collector Matthew counts money. A shaft of light cuts through darkness, divine intervention as theatrical spotlight. Matthew points at himself: "Me?"

Caravaggio placed the sacred in contemporary Roman lowlife, painting apostles as peasants with dirty feet. This chiaroscuro technique, violent light/dark contrasts, made spirituality urgent, immediate, dangerous.

The painting revolutionized religious art. Christ and Peter stand at right, barely visible, almost mundane. The light they bring, however, is supernatural, raking across the wall, illuminating Matthew and his companions counting coins. Some continue counting, oblivious; Matthew points at himself in disbelief; a young man stares at the divine visitors.

The setting is utterly contemporary: 17th-century clothing, a Roman tavern, money on the table. Caravaggio refuses idealization. These are real people in real space experiencing supernatural intervention. The sacred invades the profane; grace disrupts commerce; light transforms darkness.

Caravaggio's personal life mirrors his art's dramatic contrasts: genius and criminal, devout and violent, celebrated and exiled. He killed a man in a brawl, fled Rome with a death sentence, painted while on the run. His paintings reflect this volatility, beauty emerging from darkness, grace offered to the unworthy.

The chiaroscuro technique influenced centuries of artists: Rembrandt, Velázquez, film noir cinematographers, contemporary photographers. Caravaggio proved that light itself could be narrative, that shadow was as important as illumination, that the most dramatic moments happen at the boundary between light and dark.

37. Diego Velázquez - "Las Meninas" (1656)

Location: Prado Museum, Madrid

Medium: Oil on canvas (318 × 276 cm)

The most analyzed painting in Western art. Velázquez paints himself painting the King and Queen (visible only as reflections in a rear mirror) while their daughter Infanta Margarita and her ladies-in-waiting pose in the foreground.

We, the viewers, stand where the King and Queen stood. The painting is about the act of painting, about seeing and being seen, about power and representation. Foucault wrote a famous essay trying to decode it. It remains pleasurably unsolvable.

Here's the complexity: Velázquez paints himself at his easel, looking outward—at us, or at the King and Queen whose position we occupy. The Infanta and her attendants look in the same direction. A mirror on the back wall reflects Philip IV and Queen Mariana, are they the painting's subject, or are they watching Velázquez paint something else (perhaps us)?

A court official stands in an open doorway, about to leave or having just entered. Is this past, present, or future? The painting depicts a moment but refuses to clarify which moment, from whose perspective, for what purpose.

Michel Foucault analyzed Las Meninas as the moment classical representation reveals its own structure. The painting shows painting, the viewer becomes viewed, the subject dissolves into positions and gazes. This is 17th-century deconstruction, centuries before postmodernism, Velázquez understood representation's hall-of-mirrors complexity.

The painting's also a status claim: Velázquez wears the red cross of the Order of Santiago, an honor he received only after the painting's completion (allegedly Philip IV painted it on afterward). The artist elevates himself from craftsman to nobleman, insisting painting is intellectual labor, not manual.

38. Rembrandt - "The Night Watch" (1642)

Location: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Medium: Oil on canvas (363 × 437 cm, originally larger before trimming)

A civic guard militia portrait that explodes the genre's conventions. Instead of a static group pose, Rembrandt depicts chaotic motion, Captain Frans Banninck Cocq strides forward, his hand casting a shadow on his lieutenant's yellow jacket.

Some militia members are barely visible (they paid the same as prominent figures, lawsuit followed). Slashed by vandals in 1975, restored miraculously.

Dutch civic guard portraits were bread-and-butter commissions: group of wealthy burghers each paid equal share for equal prominence. Rembrandt, characteristically, ignored convention. He painted drama instead of documentation, the militia emerging from shadow, figures overlapping, a mysterious girl in bright dress (symbolizing Amsterdam itself?) carried along in the procession.

The "night" is actually misnamed, centuries of varnish darkening made it seem nocturnal. After cleaning, it's clearly daytime. But the name stuck, testimony to how images' reputations sometimes depend on misunderstanding.

The patrons were reportedly unhappy, some faces barely visible, composition chaotic, no orderly lineup. But Rembrandt transformed a routine commission into Baroque masterpiece. He chose artistic vision over customer satisfaction, demonstrating that even commercial work could be revolutionary.

The painting has survived fires, transfers between buildings, acid attacks, and knife slashings. Each time, conservators restored it. The canvas itself is historical document, its scars testify to art's vulnerability and resilience simultaneously.

39. Johannes Vermeer - "Girl with a Pearl Earring" (c. 1665)

Location: Mauritshuis, The Hague

Medium: Oil on canvas (44.5 × 39 cm)

A girl in a turban turns to look at us, mouth slightly open, pearl earring gleaming. We know nothing about her, model? daughter? fantasy?

Vermeer leaves no records. Her gaze is eternal: expectant, vulnerable, knowing. The "Dutch Mona Lisa," she proves that anonymity can be more powerful than fame.

The painting works because of what it withholds. No context, no setting, just black background and luminous face. The turban is exotic (Turkish? Persian?), suggesting this is costumed fantasy rather than portrait. The pearl earring (probably not real pearl, Vermeer was never wealthy) catches light, drawing attention to the girl's neck, the vulnerable turn of her head.

Her expression is almost impossible to describe: not quite smile, not quite neutral, mouth parted as if about to speak or having just inhaled. She looks over her shoulder, at what? At whom? The painting captures the instant before or after something, leaving the narrative to us.

Vermeer's technique borders on photographic: soft edges, subtle color transitions, light seemingly emanating from the face itself. He may have used camera obscura (optical device projecting images) to study light effects. His paintings have a luminous quality that seems to glow from within.

The painting was relatively unknown until the late 19th century. Tracy Chevalier's 1999 novel Girl with a Pearl Earring and subsequent film made it globally famous. Now it's an icon, endlessly reproduced, parodied, merchandised. The anonymous girl has become one of art history's most recognizable faces.

40. Kano Eitoku - "Chinese Lions" (Karajishi) (c. 1590)

Location: Imperial Collection, Kyoto (originally Kyoto Imperial Palace)

Medium: Ink, color, and gold leaf on paper (sliding door panels)

Monumental lions rendered in bold brushstrokes against gold-leaf backgrounds, the epitome of Momoyama period screen painting. Eitoku's dynamic style influenced Japanese decorative arts for centuries.

These aren't realistic lions (Japan had never seen lions); they're symbolic representations of power and protection. The fusion of Chinese subject matter, Japanese aesthetic, and gold opulence demonstrates East Asian art's sophisticated visual languages developing parallel to European Baroque.

The lions are simultaneously powerful and playful, massive paws, swirling manes, but also rolling on their backs, playing like kittens. This duality reflects Buddhist and Daoist philosophy: strength contains gentleness; power includes playfulness; ferocity and benevolence are not opposites.

The gold leaf backgrounds aren't decorative excess, they're functional. In dimly lit Japanese interiors, gold surfaces reflect and multiply available light. These screens illuminated rooms while displaying the patron's wealth and taste. Art as lighting technology.

Kano Eitoku headed the Kano school, which dominated Japanese painting for 400 years. The school operated like Renaissance workshops, master artists with many apprentices, official commissions from shoguns and emperors, maintaining style consistency across generations. This was art as dynasty.

Japanese screen painting challenges Western assumptions about painting's purpose. These aren't meant for museum walls, they're architectural elements, dividing space while providing imagery. You don't stand before them; you live with them, surrounding yourself with their presence.

ENLIGHTENMENT & REVOLUTION: When Images Became Weapons (1750-1850)

41. Qing Dynasty - "The Qianlong Emperor in Ceremonial Armour on Horseback" (1758)

Location: Palace Museum, Beijing

Medium: Hanging scroll, ink and color on silk

An Italian Jesuit missionary painter serves the Qing court, creating hybrid works blending European realism with Chinese brushwork. The Qianlong Emperor in full armor demonstrates imperial power at the Qing dynasty's apex.

This image represents cultural synthesis, Western techniques serving Eastern imperial ideology, proving that artistic influence flows in all directions.

Giuseppe Castiglione (Chinese name: Lang Shining) spent 51 years at the Qing court, creating paintings that fascinated emperors while confusing Chinese literati. His European training in perspective and anatomy collided with Chinese traditions of brushwork and composition. The result: unique hybrid style that satisfied neither tradition fully but created something new.

The Qianlong Emperor was one of history's longest-reigning monarchs (60 years), presiding over Qing China's territorial and cultural apex. He commissioned thousands of artworks, wrote poetry, collected antiquities, and considered himself a sophisticated aesthete. Having a European painter was exotic prestige, demonstrating China's ability to incorporate foreign talent while maintaining civilizational superiority.

The painting shows the emperor in full Manchu armor on horseback, traditional Chinese military portrait updated with European realism. The horse's anatomy, the armor's details, the atmospheric perspective are European; the silk support, hanging scroll format, and seal marks are Chinese.

This cross-cultural artistic exchange predates Western colonialism's destructive phase. Castiglione served by invitation, not conquest. His presence demonstrates that cultural exchange can happen through respect and mutual interest—though this would soon change as European imperial aggression intensified.

42. Jacques-Louis David - "The Death of Marat" (1793)

Location: Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

Medium: Oil on canvas (165 × 128 cm)

Revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat slumps dead in his bathtub, assassinated by Charlotte Corday. David transforms political murder into secular Pietà, Marat's arm hangs like Christ's in Michelangelo's sculpture.

The bloody knife lies on the floor; Marat still clutches Corday's letter. David painted this as propaganda for the Revolution; it remains propaganda's masterpiece.

Marat suffered from a painful skin condition, spending hours in medicinal baths while working. Charlotte Corday, a Girondin sympathizer, gained access by claiming to have information about counter-revolutionaries. Once admitted, she stabbed him. David, a committed Jacobin and friend of Marat, painted this three months after the assassination.

The composition is brilliant propaganda: Marat becomes martyr, his humble surroundings (wooden crate as desk) proving his dedication to the people. The letter in his hand: "Give this money to the mother of five children whose husband died defending his country." Marat's final act was charity. The smooth idealization of his skin erases his disfiguring disease, martyrs must be beautiful.

David painted for the Revolution with religious fervor. He voted for Louis XVI's execution, designed revolutionary festivals, created imagery justifying Terror. When the Revolution devoured itself and Robespierre fell, David narrowly escaped guillotine. He later became Napoleon's official painter, ideology flexible, artistic talent constant.

The painting demonstrates art's power to create historical memory. Marat was murdered criminal to enemies, martyr to supporters. David's painting won—this is how history remembers Marat: noble, suffering, betrayed. Images write history as surely as documents.

43. Francisco Goya - "The Third of May 1808" (1814)

Location: Prado Museum, Madrid

Medium: Oil on canvas (268 × 347 cm)

French firing squad executes Spanish civilians. The central victim, arms raised, white shirt illuminated against darkness, becomes Christ crucified by modern warfare. The soldiers are faceless; the victims are individuals.

This is the first modern anti-war painting, establishing visual language for state violence that influenced Picasso's Guernica and Eddie Adams' Saigon execution photograph.

Goya painted this six years after the event, commissioned by Spain's restored monarchy to commemorate resistance to Napoleonic occupation. But Goya wasn't celebrating nationalism, he was condemning violence itself. The faceless French soldiers are mechanisms, not individuals. The Spanish victims are terrified, defiant, resigned, complex human responses to impending death.

The central figure's white shirt glows like a beacon, drawing every eye. His pose, arms raised, palms showing stigmata-like wounds, consciously evokes crucifixion. But this isn't religious martyrdom; it's political murder. Goya secularizes Christian imagery, using it to condemn rather than sanctify.

The painting's composition is brutal: the firing squad crowds the right side, rifles aimed at point-blank range; the victims cluster left, some already dead, others watching their own imminent deaths. A monk prays; a man covers his face; others stare directly at their executioners. No heroism, no glory, just terror and waste.

Goya witnessed the Peninsular War's atrocities, documenting them in his Disasters of War print series. He understood that war's reality contradicted its rhetoric. "The Third of May 1808" is his testimony: this is what state violence looks like when propaganda is stripped away.

44. Francisco Goya - "Saturn Devouring His Son" (c. 1819-1823)

Location: Prado Museum, Madrid (transferred from Goya's house walls)

Medium: Oil mural transferred to canvas (143 × 81 cm)

The titan Saturn, bulging eyes mad, tears apart his son's headless corpse. Goya painted this directly on his dining room wall during his "Black Paintings" period, deaf, isolated, traumatized by war. He never intended public viewing.

This is the unconscious made visible, primal horror of time devouring its children.

Goya's "Black Paintings" are fourteen murals he painted on the walls of his house outside Madrid, where he lived in self-imposed isolation. Deaf from illness, embittered by political repression, he created these nightmares for no audience but himself. After his death, they were transferred to canvas and eventually to the Prado.

Saturn (Greek Kronos) ate his children to prevent the prophecy that his offspring would overthrow him. The myth represents time consuming what it creates, revolution devouring revolutionaries, fathers fearing displacement by sons. Goya painted it after witnessing the French Revolution's Terror and Spain's brutal repression.

The image is almost unwatchable: Saturn's wild eyes, his blood-smeared mouth, the half-devoured corpse he clutches. This isn't mythological distance, it's visceral horror. Goya refuses metaphor's comfort. Time doesn't gently overcome us; it tears us apart and consumes our flesh.

The painting predicts Freud, expressionism, horror cinema. Goya understood that beneath civilization's surface lurks primal violence, fathers destroying sons, power consuming challengers, time obliterating memory. He painted humanity's nightmare and hung it in his own home, living daily with darkness made visible.

45. Katsushika Hokusai - "The Great Wave off Kanagawa" (c. 1831)

Location: Multiple impressions (Metropolitan Museum, British Museum, others)

Medium: Woodblock print (25 × 37 cm)

A towering wave threatens to engulf boats while Mount Fuji sits small in the background. The most famous image in Asian art, it influenced European Impressionists and Art Nouveau designers.

Hokusai made it at age 71, part of his "Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji" series. He claimed: "At 100 I will have penetrated the mystery of life itself." He died at 89, still painting. The image demonstrates that nature's power dwarfs human ambition, a meditation on sublime terror that resonates globally.

The wave's crest breaks into claws reaching toward tiny boats. Rowers struggle against inevitable engulfment. In the distance, Mount Fuji, sacred, eternal, serene, witnesses human struggle with indifference. The composition creates tension between human vulnerability and natural force.

Hokusai's use of Prussian blue (recently imported synthetic pigment) gave the print its striking color. This was cutting-edge technology applied to traditional ukiyo-e (woodblock print) format, modernity and tradition synthesized.

The print became iconic in the West when Japanese ports opened in the 1850s. European artists, Van Gogh, Monet, Toulouse-Lautrec, collected Japanese prints, influencing Impressionism and Art Nouveau. "Japonisme" swept Europe. The Great Wave became shorthand for Japanese aesthetics, though it represented only one of many Japanese art traditions.

Hokusai signed his works "the old man mad about painting." He reinvented his style multiple times, changed his name frequently, and worked until death. The Great Wave, created in old age, demonstrates that artistic power can increase across decades. Mastery isn't youthful achievement but lifelong accumulation.

46. Eugène Delacroix - "Liberty Leading the People" (1830)

Location: Louvre Museum, Paris

Medium: Oil on canvas (260 × 325 cm)

A bare-breasted woman (representing Liberty/Marianne) leads revolutionaries over barricades, tricolour flag raised, stepping over corpses. This image of the July Revolution became France's republican icon, yet the painting disturbed authorities and was hidden for decades.

Every revolution since quotes this composition.

Delacroix painted this in response to the July Revolution of 1830, which overthrew Charles X. Though from bourgeois background, Delacroix sympathized with revolutionary ideals. He didn't participate in fighting but painted its commemoration.

Liberty isn't goddess or allegory, she's flesh-and-blood woman, breasts exposed, musket in one hand, tricolour in the other, stepping over corpses without hesitation. She's simultaneously classical ideal and contemporary Parisian. This fusion of real and symbolic makes her powerful, revolution isn't abstract principle but tangible force.

The figures surrounding her represent French society: bourgeois in top hat, street urchin with pistols, worker with sword, fallen bodies underneath. This is revolution as collective action, not elite coup. The composition's forward momentum is irresistible, Liberty advances, and we advance with her.

But the painting troubled authorities. The bare breasts seemed too erotic; the corpses too graphic; the message too radical. After brief public display, it was hidden for decades. Only the Third Republic (1870s) resurrected it as official republican symbol. Now it's on the €100 note and in every French history textbook, revolution domesticated, commodified, nationalized.

PHOTOGRAPHY'S BIRTH: When Reality Became Reproducible (1839-1900)

47. Louis Daguerre - "Boulevard du Temple" (1838)

Location: Various daguerreotype impressions

Medium: Daguerreotype photograph

The first photograph to include a human being, a man getting his boots shined on a Paris boulevard (the exposure took 10 minutes; only stationary subjects appear).

This image inaugurated photography, which Susan Sontag called "a grammar and an ethics of seeing." Everything changed: reality became reproducible, memory became mechanised, truth became contestable.

Before photography, all images were handmade, drawn, painted, carved, printed from artist-made blocks or plates. Photography mechanized vision. A machine could now record reality without human interpretation (or so it seemed, photography's "objectivity" was always an illusion).

Daguerre's image shows Boulevard du Temple nearly empty, the 10-minute exposure erased moving people and vehicles. Only one man, standing still for a shoe shine, appears. This is photography's paradox: it captures what was there but not as we experienced it. Time becomes compressed, motion becomes invisible, the photograph shows truth we never saw.

The invention of photography triggered apocalyptic predictions: painting would die, memory would become mechanical, reality would be reduced to chemical reactions on plates. Instead, photography liberated painting (if cameras could record reality, painters could explore abstraction) while creating entirely new visual possibilities.

Photography also democratized image-making. You didn't need years of training, you needed a camera and chemicals. By century's end, millions could create images. The 20th century's visual explosion began here, on this nearly empty Parisian boulevard.

48. Alexander Gardner - "The Dead of Antietam" / "A Harvest of Death" (1862-1863)

Location: Library of Congress

Medium: Albumen print photograph

Bloated corpses lie in a Gettysburg field, mouths open, limbs contorted. Gardner and his team photographed Civil War battlefields, creating the first widely distributed images of war's reality.

These weren't paintings that could beautify death, these were bodies. The photographs shocked Northern audiences, making war's cost undeniable.

Mathew Brady organized Civil War photography teams; Alexander Gardner was one of his best operators. They lugged heavy cameras and portable darkrooms to battlefields, developing glass plate negatives on site. The technical challenges were immense; the psychological cost higher.

Gardner's Gettysburg photographs showed what newspapers couldn't describe: bodies swollen beyond recognition, faces frozen in agony, personal effects scattered around corpses. These were sons, fathers, brothers—now carrion. The photographs stripped war of glory.

Northern newspapers published these images; people bought stereoscopic versions to view at home. This was entertainment as much as information—the grotesque made consumable. Photography created new relationship between violence and viewing: distant audiences could witness death without danger, becoming voyeurs of tragedy.

Gardner later admitted moving some bodies and props to improve composition, even "documentary" photography constructs reality. But the bodies were real, the death undeniable. Whether arranged or found, the images testified: war kills horribly, and cameras remember everything.

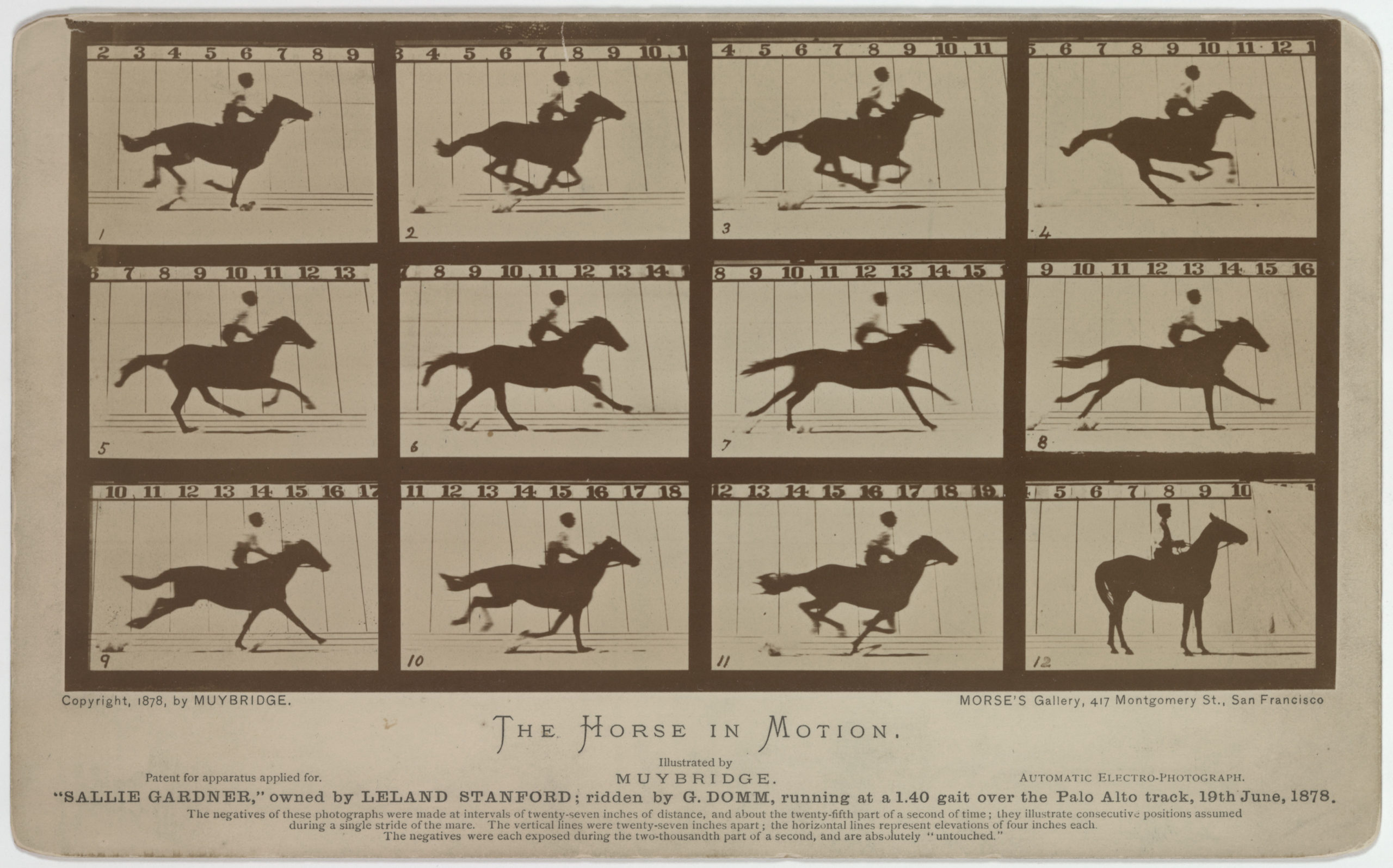

49. Eadweard Muybridge - "The Horse in Motion" (1878)

Location: Various collections

Medium: Chronophotographic sequence (12 images)

Twelve cameras captured a galloping horse in sequential images, proving all four hooves leave the ground simultaneously (settling a bet).

This wasn't just technical achievement, it revealed truths invisible to human perception, inaugurating motion pictures. Muybridge later killed his wife's lover, was acquitted, and continued photographing.

Leland Stanford (railroad tycoon) hired Muybridge to settle whether all four of a horse's hooves leave the ground during gallop. Muybridge set up twelve cameras with trip wires at his Palo Alto farm. As the horse galloped past, it triggered each camera in sequence.

The resulting images proved Stanford right, there is a moment when all hooves are airborne. But more importantly, they demonstrated photography could analyze motion invisible to human eyes. Painters had depicted horses incorrectly for centuries. Photography revealed reality's complexity.

Muybridge expanded this work, photographing humans and animals performing various actions. His books of sequential photographs became reference for artists, scientists, and eventually filmmakers. Motion pictures are Muybridge's descendants, still images played rapidly to create motion illusion.

His personal life was melodramatic: discovering his wife's affair, he tracked down her lover and shot him dead. At trial, his lawyer argued temporary insanity. Jury acquitted him. He returned to photography, proving that genius and violence can coexist. The images that revealed motion's secrets were created by a man who interrupted life with murder.

50. Lewis Hine - "Breaker Boys in Pittston, Pennsylvania" (1911)

Location: Library of Congress

Medium: Gelatin silver print photograph

Child laborers, boys aged 8-12, sit in a coal mine, faces blackened, eyes haunted. Hine photographed child labor for the National Child Labor Committee, smuggling his camera into factories and mines.

These images helped pass child labor laws. Photography as activism, as evidence, as moral witness.

Lewis Hine believed photography could change society. Working for the National Child Labor Committee, he documented children working in textile mills, coal mines, canneries, farms, often in dangerous conditions for pennies daily.

Factory and mine owners barred photographers, so Hine posed as insurance agent, fire inspector, or salesman to gain access. Once inside, he quickly photographed children, recording their ages, working hours, and wages. His captions were factual and damning: "Seven-year-old spinner in cotton mill. Works twelve hours daily."

The breaker boys photograph shows children sitting in the coal breaker building, sorting coal by hand. The work was dangerous, crushed fingers, lung disease, occasional death when children fell into machinery. The boys' expressions range from defiant to defeated, but all show premature aging, childhood stolen by industrial exploitation.

Hine's photographs circulated in magazines, lectures, exhibitions. They provided visual evidence reformers needed. Child labor laws passed state by state, then federally. Photography proved more effective than statistics, one image of an exhausted child was worth a thousand data points.

Hine demonstrated photography's activist potential: the camera as weapon against injustice, the photograph as legal evidence, the image as moral argument. Documentary photography as we know it, concerned, engaged, demanding action, begins here.

The Mirror Completed

From Giotto's weeping mourners to Lewis Hine's exploited children, these 25 images chronicle humanity's transformation from medieval subject to modern citizen. We learned to see ourselves not as God's creation awaiting heaven but as individuals deserving dignity on Earth.

The Renaissance taught us that humans, our faces, bodies, emotions, were worthy subjects. The Baroque added drama and psychological depth. The Enlightenment weaponized images for political revolution. Photography mechanized vision, making representation available to masses rather than elites alone.

By 1900, the visual revolution was complete. Images no longer belonged exclusively to churches, palaces, or wealthy patrons. Anyone with a camera could create lasting images. Anyone literate could view photographs in newspapers and magazines. The democratization of image-making had begun, though its full implications wouldn't emerge until the 20th century's technological explosions.

These 25 images taught us to see ourselves. Not as angels or demons, not as perfect classical forms, but as complex, contradictory, dignified, flawed humans navigating history's turbulence. From Raphael's philosophers to Goya's victims to Hine's child laborers, we learned that every human deserves to be seen, recorded, remembered.

The journey continues. In our next installment, we'll explore how the 20th century exploded representation itself, how modernism fractured reality, how world wars demanded documentation, how images became weapons of mass persuasion, and ultimately how digital technology gave everyone the power to create, distribute, and manipulate images instantly.

But that transformation was only possible because these 25 images first taught us that seeing, truly seeing ourselves and others, is both art and ethics, both beauty and responsibility.

The eternal gaze continues. These images aren't historical artifacts, they're living lessons in how to witness, how to testify, how to remember.

Next: Modern Revolutions and the Digital Explosion - Images 51-75

previous

When Vision Becomes Destiny: The First 25 Images That Shaped Human Consciousness

next

Modern Revolutions and the Digital Explosion: Images That Shattered and Rebuilt Reality

Share this

Dinis Guarda

Author

Dinis Guarda is an author, entrepreneur, founder CEO of ztudium, Businessabc, citiesabc.com and Wisdomia.ai. Dinis is an AI leader, researcher and creator who has been building proprietary solutions based on technologies like digital twins, 3D, spatial computing, AR/VR/MR. Dinis is also an author of multiple books, including "4IR AI Blockchain Fintech IoT Reinventing a Nation" and others. Dinis has been collaborating with the likes of UN / UNITAR, UNESCO, European Space Agency, IBM, Siemens, Mastercard, and governments like USAID, and Malaysia Government to mention a few. He has been a guest lecturer at business schools such as Copenhagen Business School. Dinis is ranked as one of the most influential people and thought leaders in Thinkers360 / Rise Global’s The Artificial Intelligence Power 100, Top 10 Thought leaders in AI, smart cities, metaverse, blockchain, fintech.