When Vision Becomes Destiny: The First 25 Images That Shaped Human Consciousness

Dinis GuardaAuthor

Mon Dec 15 2025

Explore humanity's first 25 most powerful images spanning 40,000 years—from cave paintings to medieval masterpieces. A global journey through visual consciousness by Dinis Guarda.

A Journey Through 40,000 Years of Visual Memory

From “ The most Influential Powerful 100 Images in History of Humanity” mini-book By Dinis Guarda

Introduction: The Eternal Gaze

What makes an image powerful? Not beauty alone. Not technical mastery. Not even truth, for the most transformative images sometimes lie.

Power resides in an image's metaphysical capacity to mirror and alter human consciousness itself, to split history into "before" and "after," to make the invisible visible, to transform how millions perceive reality across time. A powerful image doesn't just document a moment; it creates one, crystallizing complex narratives into a single frozen instant that reverberates across centuries.

73,000 years ago, long before agriculture, before cities, before written language, a Homo sapiens in Blombos Cave, South Africa, drew a cross-hatched pattern in red ochre on a stone flake. This abstract design, discovered in 2018, is the oldest known image created by human hands. It proves our ancestors were capable of abstraction and symbolic thought tens of millennia before they built temples or wrote laws.

The human impulse to create images predates almost everything we consider "civilisation." We made images before we made governments, before we made gods, before we made ourselves into the complex societies we recognize today.

For too long, art history has been written as a Western narrative, as if Michelangelo and Monet constitute the entirety of human visual achievement. This is a lie by omission. While Europe painted Renaissance frescoes, India carved temple complexes where Shiva dances the universe into existence. While Leonardo sketched anatomy, China perfected landscape painting as philosophical practice. While Rembrandt mastered chiaroscuro, Aboriginal Australians maintained 65,000 years of continuous artistic tradition.

This compendium stands on an unshakeable premise: each human being IS humanity. Therefore, powerful images emerge from every civilization, every continent, every cultural tradition. When an Aboriginal artist paints a Dreamtime story, all of humanity paints. When a Chinese calligrapher captures qi in brushstrokes, we all participate in that cosmic breath.

What follows is not merely a list. It is a visual genealogy of human consciousness—tracing how we learned to see, to represent, to remember, and ultimately to transcend our mortality through images.

We begin where we must: in the darkness of caves, where human hands first reached toward visual eternity.

DEEP PREHISTORY: When Hands First Spoke (42,000 BCE - 10,000 BCE)

1. Hand Stencils of El Castillo Cave (c. 39,000 BCE)

Location: Cantabria, Spain

Medium: Red ochre on limestone cave wall

The oldest known cave paintings in Europe, negative handprints created by blowing pigment over a hand pressed against rock. These aren't decorations; they're declarations: "I was here. I existed. Bear witness."

Forty millennia later, these hands still reach toward us across the void, proving that the first human impulse was to leave a mark that would outlast mortality itself. Recent dating suggests some may have been made by Neanderthals, making them not just human art, but evidence of our cousin species' symbolic thinking.

The simplicity is deceptive. Creating these stencils required understanding pigment preparation, lung capacity control, and, most profoundly, the concept of representation itself. The hand on the wall is both the hand and about the hand. This leap into symbolic thought changes everything.

2. Sulawesi Cave Art - Warty Pig Painting (c. 45,500 years ago)

Location: Leang Tedongnge cave, Sulawesi, Indonesia

Medium: Red ochre on limestone

The oldest known figurative painting, a Sulawesi warty pig rendered in profile, 136 cm wide. This shatters the Eurocentric narrative that sophisticated art began in France and Spain. Southeast Asian artists were painting naturalistic animals millennia before Lascaux.

The pig confronts two hand stencils, suggesting narrative: human and animal in dialogue. This isn't random decoration, it's storytelling, relationship, meaning-making. The artist understood anatomy, proportion, and how to use the cave wall's natural contours to create three-dimensionality.

For decades, Western archaeology assumed Europe was the cradle of artistic achievement. This pig, dated definitively in 2021, forces us to reimagine the global distribution of human creativity. Art didn't spread from one center, it exploded simultaneously across continents as our species learned to externalize imagination.

3. Aboriginal Rock Art - Nawarla Gabarnmang (c. 28,000 years ago)

Location: Arnhem Land, Northern Territory, Australia

Medium: Charcoal and ochre on rock shelter ceiling

Among the oldest dated Aboriginal rock art, this site contains thousands of images layered across 28 millennia, a palimpsest of continuous creation. The shelter's ceiling is covered with geometric patterns, animal tracks, and later additions including X-ray art showing animals' internal organs.

This isn't "prehistoric" art, it's part of a living tradition connecting contemporary Aboriginal people directly to Paleolithic ancestors. The same families who created these images 28,000 years ago still maintain the site today, adding new paintings, caring for old ones, transmitting knowledge across hundreds of generations.

Aboriginal Australians represent the oldest continuous culture on Earth, over 65,000 years of unbroken artistic, spiritual, and social tradition. Their art isn't decoration; it's topographic memory, spiritual mapping, legal documentation, all fused into image. The songlines that traverse the continent are simultaneously song, story, map, and visual art.

4. The Lion-Man of Hohlenstein-Stadel (c. 40,000 BCE)

Location: Swabian Jura, Germany

Medium: Mammoth ivory sculpture (31.1 cm tall)

Humanity's oldest known zoomorphic sculpture, a human body with a lion's head, carved with stone tools from mammoth tusk. This object required 400+ hours of work. Someone sat in firelight, carefully scraping ivory, envisioning something that had never existed.

It proves that 40,000 years ago, humans were already creating impossible beings, blending reality with imagination. This represents shamanic transformation, the birth of mythology, our eternal obsession with transcending physical form. The figure stands upright like a human but possesses a lion's power and ferocity.

The Lion-Man demonstrates that art and religion emerged together. We didn't first worship gods and then depict them, the act of depicting created the divine. By carving the impossible, we made it real. This is humanity's first fantasy, first science fiction, first theology rendered in three dimensions.

5. Venus of Willendorf (c. 25,000 BCE)

Location: Willendorf, Austria

Medium: Limestone with red ochre traces (11 cm tall)

The archetypal “Venus figurine”, massive breasts, belly, and buttocks; no facial features. Hundreds of similar figurines span from France to Siberia, suggesting a widespread symbolic system we can no longer fully decode.

Fertility cult object? Self-portrait by a pregnant woman looking down at her own body? We project our assumptions, but the image's power remains: the female body as the source of all life, rendered in stone for eternity.

The absence of facial features is telling. This isn't a portrait of an individual but an archetype, Woman as Life-Giver, as Earth Mother, as the mystery of generation itself. For 25,000 years, this little limestone figure has provoked debate about how our ancestors viewed gender, reproduction, and the sacred.

6. Lascaux Cave Paintings - The Great Hall of the Bulls (c. 17,000 BCE)

Location: Dordogne, France

Medium: Mineral pigments on limestone (largest aurochs: 5.2 meters long)

The Sistine Chapel of prehistory. These aren't primitive scratches, they're sophisticated compositions using the cave's natural contours to create three-dimensionality. The bulls gallop in eternal motion, their power and grace captured by artists who understood anatomy, movement, and perspective.

When discovered in 1940 by teenagers and a dog, they forced us to reimagine our ancestors' cognitive capabilities. These artists mixed pigments, built scaffolding, worked by firelight in deep underground chambers. They created images so powerful that modern visitors weep before them.

Now closed to preserve them (human breath was causing deterioration), they survive through photographs, images of images. The original paintings live in darkness while reproductions educate millions. Which is more "real"—the unreachable original or the accessible copy?

7. Chauvet Cave - The Panel of Horses (c. 30,000-32,000 BCE)

Location: Ardèche, France

Medium: Charcoal and ochre on limestone

Older than Lascaux yet more sophisticated—horses rendered with shading, perspective, and motion blur. The artists scraped the cave wall first to create lighter surface, then drew with charcoal and fingers. These aren't pictures of horses; they are horses, summoned into existence through ritual and skill.

Werner Herzog's documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams (2010) made these images globally accessible through 3D photography, allowing millions to experience what only a few specialists can view in person. Technology extends the images' power across space and time.

The Chauvet horses demonstrate that artistic sophistication doesn't evolve linearly. The oldest representational art is often the most accomplished. Our ancestors 32,000 years ago possessed the same intelligence, creativity, and aesthetic sensibility we have today, only their canvas was limestone instead of canvas.

ANCIENT CIVILIZATIONS: When Images Became Power (10,000 BCE - 500 CE)

8. Indus Valley Seal - "Pashupati" or Proto-Shiva (c. 2500-1900 BCE)

Location: Mohenjo-daro, Indus Valley (modern Pakistan)

Medium: Carved steatite seal (3.56 × 3.53 cm)

A seated figure in yogic posture, surrounded by animals, possibly the earliest representation of Shiva as Pashupati (Lord of Beasts). The Indus script above remains undeciphered, making these seals among archaeology's great mysteries.

Thousands were produced for trade, administration, or ritual. They prove that by 2500 BCE, the Indus civilization had developed sophisticated iconography we still cannot fully read. The figure's yogic pose suggests continuity with later Hindu practice, a visual tradition stretching unbroken across 4,500 years.

These tiny seals contain entire cosmologies we've lost. Each animal, each symbol, each decorative element encoded meaning for their creators. We can see the images clearly; we cannot read them. They remind us that visual power sometimes resides precisely in what remains mysterious.

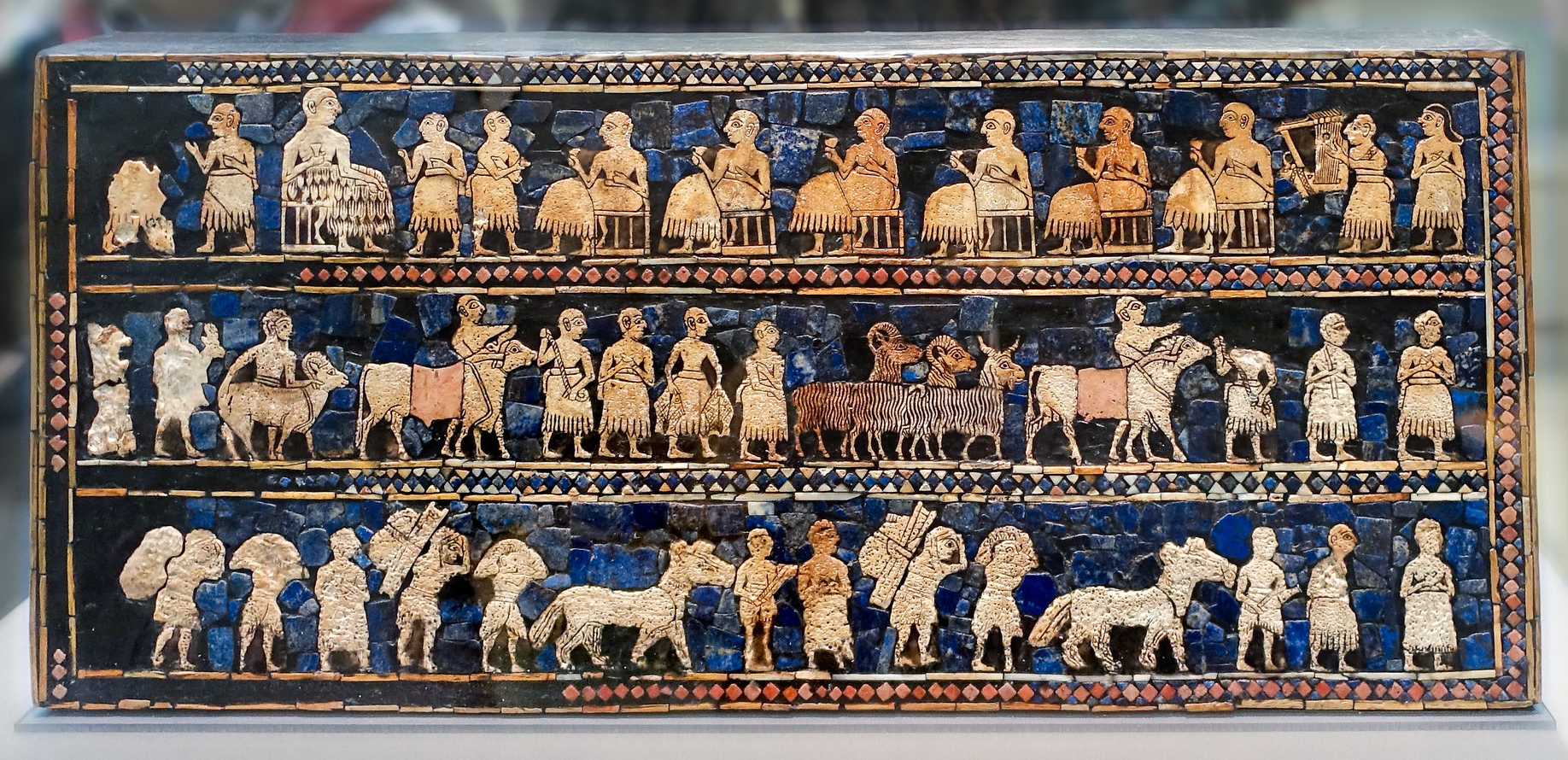

9. The Standard of Ur (c. 2600 BCE)

Location: Ur, Mesopotamia (modern Iraq)

Medium: Shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone mosaic (21.5 × 49.5 cm)

A double-sided wooden box showing "War" and “Peace”, the first visual propaganda. One side depicts military victory with chariots trampling enemies; the other shows a celebratory banquet. This is humanity's earliest surviving narrative artwork that explicitly equates military conquest with civilizational legitimacy.

The craftsmanship is extraordinary, tiny mosaic pieces arranged in registers like a comic strip, telling the story of Sumerian military might and prosperity. Soldiers march in formation, prisoners are paraded, the king feasts while musicians play. This is empire's visual justification: we conquer, therefore we deserve to rule.

Found in a royal tomb at Ur, it demonstrates that 4,600 years ago, rulers understood images' propagandistic power. Visual narratives can justify violence, celebrate authority, and construct historical memory that serves the powerful.

10. The Great Sphinx of Giza (c. 2500 BCE)

Location: Giza Plateau, Egypt

Medium: Carved limestone monolith (73.5 meters long, 20 meters tall)

A lion's body with a pharaoh's head, the ultimate power portrait. For 4,500 years it has gazed eastward toward the rising sun, guarding the pyramids. The Sphinx's face was mutilated (possibly by Sufi iconoclasts, possibly by Napoleon's troops, history debates).

Yet even defaced, it remains the definitive image of immortal authority. The Sphinx doesn't request power, it assumes it. The fusion of human intelligence with animal strength, individual ruler with cosmic guardian, creates an image of sovereignty so absolute it requires no explanation.

Scale matters. At 73.5 meters long, the Sphinx can't be fully comprehended from ground level. You must walk around it, let its mass dominate your vision, feel dwarfed by carved stone. This is power made architectural—authority you must physically navigate.

11. The Mask of Tutankhamun (c. 1323 BCE)

Location: Valley of the Kings, Egypt

Medium: Gold inlaid with lapis lazuli, carnelian, obsidian, turquoise (54 cm tall, 10.23 kg)

When Howard Carter opened Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922 and saw this mask, he wrote: "wonderful things." The teenage pharaoh's idealized face in solid gold became the definitive image of ancient Egypt, more recognizable globally than any living Egyptian leader.

It represents death's transformation into eternity. Tutankhamun was a minor pharaoh who died young, accomplished little, and was nearly forgotten. His mask made him immortal. The image transcends the individual, this is what divine kingship looks like, what eternal life promises, what gold can purchase when combined with faith and craft.

The mask's power lies partly in its discovery story. Carter's excavation was global news, photographs circulated worldwide, "Egyptomania" swept Western culture. The mask became modernity's encounter with antiquity, proof that ancient civilizations achieved heights we can barely comprehend.

12. Sanchi Stupa - The Great Stupa Gateway (Torana) (3rd century BCE - 1st century CE)

Location: Sanchi, Madhya Pradesh, India

Medium: Carved sandstone

Four ornate gateways (toranas) surround the Great Stupa, each covered with relief sculptures depicting Jataka tales (Buddha's previous lives), scenes from his life (represented symbolically, no human Buddha figure yet), and celestial beings.

These gateways represent early Buddhist narrative art's sophistication. The Buddha is shown through symbols: footprints, empty throne, Bodhi tree, wheel. This demonstrates that the most powerful images sometimes refuse direct representation. The absence becomes presence; the symbol becomes more potent than the depicted.

Emperor Ashoka commissioned the original stupa in the 3rd century BCE after his conversion to Buddhism and rejection of violence. The gateways added later transform architecture into scripture, pilgrims walk through carved narratives, their bodies moving through Buddha's teachings made stone.

13. Terracotta Army (c. 210 BCE)

Location: Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, China

Medium: Terracotta sculptures (estimated 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots, 670 horses)

An entire army buried to serve Emperor Qin Shi Huang in the afterlife, each soldier's face unique, ranks differentiated by armor and posture. Discovered in 1974 by farmers digging a well, they revealed Chinese imperial power's megalomaniacal scale.

This isn't a single image but a landscape of images, death's bureaucracy rendered in clay. The emperor who unified China couldn't imagine an afterlife without armies, administrators, horses, chariots. So he had them made, fired, and buried in military formation.

The individuality of each face is haunting. These aren't generic soldiers, they're portraits. Someone modeled for each figure; artisans studied real faces and recreated them in clay. An army of individuals created to serve one man's immortality fantasy.

14. The Parthenon Frieze (Elgin Marbles) (447-432 BCE)

Location: Parthenon, Athens (now British Museum and Acropolis Museum)

Medium: Carved Pentelic marble relief (originally 160 meters long)

The Panathenaic procession, Athens' citizens bringing a new robe to Athena's statue. This wasn't just decoration; it was political ideology rendered in marble, establishing Athenian democracy as divinely sanctioned.

The controversy over the "Elgin Marbles" proves images create ongoing power struggles across millennia. Lord Elgin removed roughly half the frieze in the early 1800s; Greece has demanded its return ever since. Who owns cultural heritage? Can images belong to one nation when they represent human achievement? The debate continues.

The frieze depicts real Athenians, not gods or heroes but citizens participating in civic ritual. This democratization of representation mirrors Athens' democratic experiment. Everyone can be immortalized; everyone belongs in the visual record.

15. The Alexander Mosaic (c. 100 BCE, copying 310 BCE original)

Location: House of the Faun, Pompeii

Medium: Mosaic (5.82 × 3.13 meters, approximately 1.5 million tesserae)

Alexander the Great charges toward Darius III at the Battle of Issus. The Persian king's terrified face as he flees in his chariot captures the moment empire transfers. This image established the iconography of Alexander as unstoppable conqueror, an image that obsessed everyone from Julius Caesar to Napoleon.

The mosaic is technically astounding, 1.5 million tiny tiles creating subtle shading, complex movement, emotional intensity. The Roman mosaicist copied a Greek painting (now lost), demonstrating that even 2,000 years ago, important images were reproduced, circulated, and reinterpreted.

Alexander's eyes lock on Darius while his horse tramples a Persian soldier. Darius extends his hand, whether in command to retreat or in futile gesture of defense, we can't know. The ambiguity enhances drama. This is the instant when power shifts, when history pivots, when one man's will overcomes another's.

16. Nok Terracotta Sculptures (c. 1500 BCE - 500 CE)

Location: Nok, Nigeria

Medium: Terracotta (various sizes, up to life-size)

Among Africa's oldest sculptural traditions outside Egypt, Nok terracottas depict humans and animals with distinctive triangular eyes and elaborate hairstyles. These sculptures influenced later African art traditions and demonstrate that sophisticated representational art flourished in sub-Saharan Africa contemporaneously with classical Greece and Rome.

The tradition remained unknown to Western archaeology until 1928, a reminder that "art history" is always incomplete. How many other traditions have been lost, overlooked, or deliberately ignored because they didn't fit colonial narratives about African "primitiveness"?

The Nok style is immediately recognizable, those triangular eyes, the elaborate coiffures, the serene expressions. These aren't generic figures but individualized portraits with distinct personalities, social roles, and spiritual significance. They prove that African sculptural achievement spans millennia.

17. Ajanta Cave Paintings - Padmapani Bodhisattva (c. 5th century CE)

Location: Ajanta Caves, Maharashtra, India

Medium: Natural pigment fresco on rock wall

The Padmapani (lotus-bearing) Bodhisattva stands in tribhanga pose, the graceful triple-bend that became Indian art's signature. His serene face, elaborate jewelry, and celestial attendants create an image of enlightened compassion.

These murals influenced Asian art from Sri Lanka to Japan. The caves were abandoned for a millennium, rediscovered by British soldiers in 1819, revealing Buddhist visual theology at its apex. Monk-artists painted these frescoes as meditation, as teaching tool, as offering. Each brushstroke was prayer.

The Padmapani's gentle expression embodies bodhisattva compassion, the being who achieves enlightenment but delays entering nirvana to help all beings reach liberation. His beauty isn't sensual but spiritual, demonstrating that aesthetic perfection can serve religious function without diminishing either.

18. Olmec Colossal Heads (c. 1500-400 BCE)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-185295512-5c4b1deb46e0fb0001119fbd.jpg)

Location: San Lorenzo and La Venta, Gulf Coast Mexico

Medium: Basalt boulders (each 6-10 feet tall, up to 50 tons)

Seventeen massive stone heads depicting Olmec rulers, African-like features, elaborate headdresses, individualized faces. Carved from basalt quarried 50+ miles away and transported through jungle and swamp without wheels or beasts of burden.

These are Mesoamerica's oldest monumental sculptures, predating Maya and Aztec civilizations. They announce: power can be literally monumental, permanence achieved through sheer scale. Each head weighs up to 50 tons, moving them was architectural feat equivalent to pyramid construction.

The African features sparked absurd theories about trans-Atlantic contact. The simple truth: humans globally share physical characteristics; not every similarity requires external influence. The Olmec created these masterpieces independently, developing sculptural traditions as sophisticated as any in the ancient world.

MEDIEVAL SYNTHESIS: When Faith Found Form (500-1400 CE)

19. Hagia Sophia Mosaic of Christ Pantocrator (c. 1261 CE)

Location: Hagia Sophia, Constantinople/Istanbul

Medium: Gold and glass mosaic

Christ as “Ruler of All”, his right hand blessing, his left holding the Gospel. His face is asymmetric: one side merciful, the other stern. For centuries, Christians entered Hagia Sophia and saw God judging them.

When Ottomans conquered Constantinople (1453), they plastered over these images; when Atatürk made it a museum (1935), they were revealed again. In 2020, it became a mosque; the mosaics remain covered during prayer—an image so powerful it must be hidden.

The Pantocrator doesn't smile. He gazes with absolute authority, weighing souls, knowing everything. This is God as emperor, theology as political power, divinity made architecturally overwhelming. Stand beneath it and feel your insignificance measured against eternity.

20. The Book of Kells - Chi Rho Page (c. 800 CE)

Location: Probably Iona, Scotland (now Trinity College Dublin)

Medium: Vellum manuscript illumination with pigments including lapis lazuli

The most elaborate page in medieval manuscript history, the Greek letters Chi-Rho (☧, representing Christ) explode into spirals, animals, angels, and abstract patterns so intricate that microscopic examination reveals details invisible to naked eye.

This is prayer as visual ecstasy, the divine made visible through obsessive craft. Irish monks spent months creating each page, mixing pigments from across the known world (lapis lazuli from Afghanistan), bending over vellum in cold scriptoriums, transmuting faith into beauty.

The Chi-Rho page demonstrates that the medieval world wasn't “dark”, it was illuminated, literally. These manuscripts preserved knowledge through Europe's tumultuous centuries while simultaneously creating some of history's most intricate artworks.

21. Borobudur Temple Reliefs (c. 750-850 CE)

Location: Central Java, Indonesia

Medium: Volcanic stone relief panels (2,672 panels total)

The world's largest Buddhist temple, Borobudur is structured as a mandala in stone, pilgrims ascend through realms of desire, form, and formlessness toward enlightenment at the summit. The relief panels narrate Buddha's lives and teachings across 1,460 narrative panels.

This is architecture as image, pilgrimage as reading, sacred geography made walkable. You don't just view Borobudur, you climb through it, your body tracing the path from earthly suffering to spiritual liberation. Each level represents a stage of consciousness; each relief panel teaches a lesson.

Abandoned after Islam's arrival, buried by volcanic ash, rediscovered in 1814, proving great images can sleep for centuries. Dutch colonizers excavated it; Indonesian independence reclaimed it; now millions of pilgrims and tourists circumambulate its terraces annually.

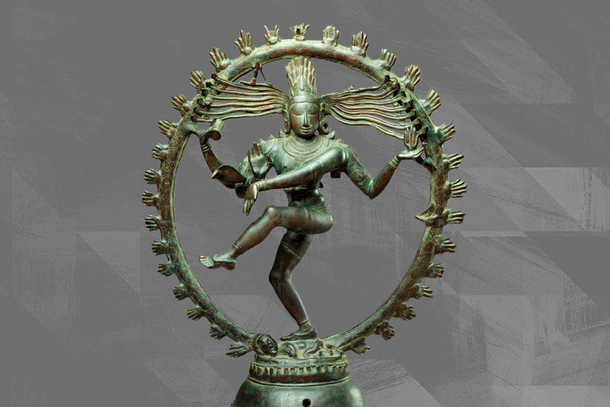

22. Shiva Nataraja - The Cosmic Dancer (c. 11th century CE)

Location: Tamil Nadu, India (multiple bronze castings, museums worldwide)

Medium: Bronze (various sizes, typically 2-3 feet tall)

Shiva dances within a ring of flames, creating, preserving, and destroying the universe with each movement. His four arms hold drum (creation's sound), fire (destruction), abhaya mudra (fear not), and point to uplifted foot (liberation). The dwarf beneath represents ignorance trampled.

This is cosmology as choreography, theology as sculpture. Physicist Fritjof Capra argued it anticipates quantum mechanics' dance of subatomic particles. The image became so iconic that CERN has a Nataraja statue at their headquarters, physics recognizing metaphysics.

Chola Dynasty bronze casters perfected lost-wax technique to create hundreds of these sculptures. Each one is unique yet iconographically consistent. Shiva's dance is both cosmic (universe's endless cycle) and intimate (individual's spiritual transformation). The image operates simultaneously at multiple scales.

23. Ife Bronze Head (c. 12th-15th century CE)

Location: Ife, Nigeria

Medium: Bronze (lost-wax casting)

Naturalistic portrait heads from the Yoruba city of Ife, displaying technical mastery equal to any European Renaissance bronze. When discovered by Westerners in early 20th century, they couldn't believe Africans created them, inventing theories of lost Atlantean civilizations or Portuguese intervention.

These heads prove African metallurgical and sculptural sophistication centuries before European contact, demolishing racist assumptions about African artistic capabilities. The Ife casters achieved bronze work rivaling Donatello, but did it 400 years earlier.

The faces are serene, idealized yet individual, wearing elaborate regalia. These likely represented Yoruba royalty (the Ooni of Ife) or deities. Their naturalism contrasts with the more abstract Nok tradition, showing African art's stylistic diversity across time and geography.

24. Angkor Wat - The Churning of the Ocean of Milk Relief (c. 12th century CE)

Location: Angkor Wat, Cambodia

Medium: Sandstone bas-relief (approximately 50 meters long)

Gods and demons churn the cosmic ocean using the serpent Vasuki wrapped around Mount Mandara, creating amrita (nectar of immortality). This Hindu creation myth rendered on temple walls demonstrates the Khmer Empire's artistic and architectural sophistication.

Angkor Wat itself, the world's largest religious monument, is an image at city-scale, microcosm of the Hindu universe translated into stone. The temple's five towers represent Mount Meru's peaks; its moats represent cosmic oceans. Walking through Angkor Wat is walking through cosmology.

The relief's scale is staggering, 50 meters of continuous narrative carved into sandstone. Dozens of figures pull the serpent rope; apsaras (celestial dancers) emerge from the churned ocean; Vishnu oversees the creation. This is mythology made architectural, belief made permanent.

25. Bayeux Tapestry - Death of Harold (c. 1070-1080 CE)

Location: Probably Canterbury, England (now Bayeux, France)

Medium: Embroidered wool on linen (70 meters long, 50 cm tall)

History's first documentary film, the Norman Conquest told in 75 scenes. Harold Godwinson takes an arrow to the eye (or does he? the ambiguous image has sparked debate for centuries). This is the victors writing history in thread, justifying William's invasion as divinely ordained.

The Bayeux Tapestry isn't technically a tapestry (it's embroidered, not woven) and wasn't made in Bayeux (probably Canterbury). But it remains medieval Europe's most important historical image, a 70-meter-long narrative explaining why William had God's blessing to conquer England.

The embroiderers included marginal details: animals, agricultural scenes, sexual imagery. These borders comment on the main narrative, sometimes satirically. This is sophisticated visual storytelling, foreground and background, main plot and subtext, all integrated into seamless historical propaganda.

The First 25 Witnesses

From ochre hands pressed against Spanish cave walls 39,000 years ago to medieval embroiderers documenting conquest, these first 25 images trace humanity's evolution from biological being to symbolic creator.

We learned to represent ourselves, then our gods, then our histories. We moved from cave walls to carved stone, from individual expression to state propaganda, from anonymous hands to named empires.

But notice what remains constant: the impulse to make the invisible visible, to freeze time, to communicate across centuries. The Blombos artist who drew cross-hatches 73,000 years ago and the Bayeux embroiderers working 950 years ago shared the same fundamental drive, to leave marks that outlast mortality.

These 25 images span 40,000 years, six continents, dozens of cultures. They represent humanity's visual awakening—our discovery that we can externalize inner vision, share it with others, and transmit it across time.

In the next installment, we'll explore how Renaissance humanism transformed this visual legacy, how photography mechanized memory, and how modernity exploded representation itself.

But first, pause. Consider: Which of these 25 images moves you most? Which challenges your assumptions? Which proves that powerful vision emerges everywhere humans gather, think, create?

The eternal gaze continues. These images aren't dead history, they're living witnesses to our species' endless capacity to see, to show, to remember.

Each human being IS humanity. Every image is our collective inheritance.

Stay tuned for the Next article: Renaissance Humanism and the Birth of the Modern Gaze - Images 26-50

previous

What a Small Indian Village Teaches the World About Sustainability

next

Renaissance Humanism and the Birth of the Modern Gaze: Images That Taught Us to See Ourselves

Share this

Dinis Guarda

Author

Dinis Guarda is an author, entrepreneur, founder CEO of ztudium, Businessabc, citiesabc.com and Wisdomia.ai. Dinis is an AI leader, researcher and creator who has been building proprietary solutions based on technologies like digital twins, 3D, spatial computing, AR/VR/MR. Dinis is also an author of multiple books, including "4IR AI Blockchain Fintech IoT Reinventing a Nation" and others. Dinis has been collaborating with the likes of UN / UNITAR, UNESCO, European Space Agency, IBM, Siemens, Mastercard, and governments like USAID, and Malaysia Government to mention a few. He has been a guest lecturer at business schools such as Copenhagen Business School. Dinis is ranked as one of the most influential people and thought leaders in Thinkers360 / Rise Global’s The Artificial Intelligence Power 100, Top 10 Thought leaders in AI, smart cities, metaverse, blockchain, fintech.