The Digital Convergence: When Images Became Everything, Everywhere, All at Once

Dinis GuardaAuthor

Thu Dec 18 2025

Explore 73,000 years of image-making: from prehistoric cave art to NFTs and AI. Discover how the 21st century transformed images into everything, currency, surveillance, infinite scroll, and why some sacred images still resist commodification. By Dinis Guarda.

From Blockchain to Black Holes: How the 21st Century Dissolved the Boundary Between Image and Reality

From “ The most Influential Powerful 100 Images in History of Humanity” mini-book By Dinis Guarda

The Image Infinite

We have arrived at the endpoint, or perhaps the vanishing point, of humanity's 73,000-year journey with images.

The 21st century didn't just accelerate visual culture; it fundamentally transformed what images are, how they function, and what they mean. We no longer merely create images—we inhabit them. We don't just view images—we are viewed by them. The boundary between image and reality, between representation and existence, between seeing and being seen has dissolved entirely.

Consider: In 2023, humans created more images in a single day than existed in total throughout the entire 19th century. Instagram users upload 95 million photos daily. Surveillance cameras capture 4 billion hours of footage. Satellites photograph Earth continuously. Artificial intelligence generates photorealistic images from text prompts. Deepfakes make anyone appear to say anything. Virtual influencers with millions of followers don't physically exist.

We have entered the age of image totality, where everything is image, image is everything, and reality itself becomes optional.

These final 25 images (76-100) trace this transformation: from early internet viral phenomena to smartphone revolution, from social media's visual explosion to AI-generated imagery, from climate crisis documentation to the James Webb telescope showing us the universe's infancy, and finally returning full circle to Aboriginal Dreamtime art, the oldest continuous image-making tradition, still alive, still creating, reminding us that some images resist commodification, circulation, and capture.

This section is different from the previous three. Many of these "images" aren't singular photographs or paintings but phenomena, viral memes, satellite datasets, algorithmic composites, blockchain tokens, collective documentation projects. The image has become distributed, decentralized, democratized to the point where authorship dissolves and everyone is simultaneously creator and consumer.

We'll explore how images became currency (NFTs), how they became weapons (misinformation campaigns), how they became infinite (social media feeds), how they became surveillance (facial recognition), and ultimately how they became autonomous (AI generation).

But we'll also discover resistance: artists who challenge image proliferation, communities who refuse to let sacred images circulate, activists who weaponize documentation against power, and the stubborn persistence of ancient traditions that predate and will outlast our digital frenzy.

The eternal gaze has become the infinite scroll. We can no longer look away—the images won't let us. But perhaps, hidden within this overwhelming visual noise, we can still find signal: images that matter, that testify, that resist, that remember, that imagine futures beyond the algorithmic present.

We begin where the 20th century left us: at the threshold of the internet age, when images first learned to move at the speed of light.

THE INTERNET AGE: When Images Learned to Reproduce Themselves (1990-2010)

76. Banksy - "Girl with Balloon" (Self-Destructing Version) (2002/2018)

Location: Various locations (stencil); Sotheby's auction house (shredded version)

Medium: Spray paint stencil; later oil on canvas

A little girl reaches for a heart-shaped red balloon floating away. In 2018, the painting sold at auction for $1.4 million, then immediately self-shredded via hidden mechanism, stopping halfway.

Retitled Love is in the Bin, it was later resold for $25.4 million. The destruction doubled its value.

Banksy, anonymous street artist, created "Girl with Balloon" as stencil graffiti in 2002. The image appeared on London walls, bridges, underpasses, a child losing something precious, reaching futilely as it escapes. The composition is simple, sentimental, effective. It became Banksy's most recognized image.

In 2018, a canvas version went to auction at Sotheby's. The moment the hammer fell at £1.042 million, a hidden shredder in the frame activated, pulling the canvas through blades. Gasps. Confusion. The painting hung in strips, half-destroyed. Banksy posted video on Instagram: "Going, going, gone..."

The stunt was performance art critiquing the art market: art's value is arbitrary, assigned by wealthy collectors, disconnected from meaning. By destroying the painting at its moment of peak market value, Banksy demonstrated that destruction creates rather than diminishes value, he shredded version was worth more than the intact original.

The buyer chose to keep it. Sotheby's verified it as "the first artwork in history to have been created live during an auction." Renamed Love is in the Bin, it sold again in 2021 for £18.5 million ($25.4 million), eighteen times its pre-shredding price.

This is 21st-century art's logic: spectacle creates value, virality equals legitimacy, the documentation (photos, videos, social media frenzy) matters more than the object. Banksy understands this perfectly, his anonymity is brand, his criminality is marketing, his anti-capitalism is extremely profitable.

The image itself, girl losing balloon, becomes metaphor for art itself: we grasp at meaning as it floats away, we assign value to what we've lost, we destroy what we love through our need to possess it.

77. Anonymous - "Aylan Kurdi on Beach" (September 2, 2015)

Location: Bodrum, Turkey

Medium: Photograph

Three-year-old Syrian refugee Aylan Kurdi lies on a Turkish beach, face down, waves lapping at his body. His family drowned fleeing Syria for Europe.

The image went viral instantly. European countries temporarily liberalized refugee policies. Then the moment passed; borders closed again. The image's power proved both immense and temporary.

Nilüfer Demir, Turkish photojournalist, arrived at Bodrum beach on September 2, 2015, responding to reports of bodies washing ashore. She found Aylan Kurdi, three years old, lying in the surf wearing a red shirt and blue shorts. His brother and mother had also drowned; only his father survived.

Demir photographed the scene, not exploitation but testimony. The image circulated within hours: Twitter, Facebook, news sites globally. A three-year-old's body, face down on a tourist beach, made refugee crisis viscerally real.

The response was unprecedented: European leaders pledged to accept more refugees, donations to refugee organizations spiked, public opinion shifted toward compassion. Germany opened borders; other countries followed. The image seemed to change everything.

But within weeks, the moment passed. Paris attacks (November 2015) shifted sentiment toward fear. Borders closed; policies hardened; refugees were once again threats rather than victims. Aylan's death mobilized temporary compassion that evaporated when political convenience demanded.

This reveals 21st-century image culture's paradox: images circulate instantly, creating global awareness and immediate response, yet their impact is superficial and temporary. We're moved, we share, we move on. The algorithmic feed buries yesterday's crisis under today's content. Attention is infinite but infinitesimally thin.

Demir defended her decision to photograph and publish: "I thought, 'This is the only way to make people see what is happening.' His family, his relatives, they gave permission." Yet questions persist: Did the image help refugees or exploit one child's death? Did it create lasting change or fleeting sentiment?

Both are true. The image matters, it pierced indifference, forced recognition, saved some lives by mobilizing aid. Yet it also demonstrates images' limitations, viral attention doesn't equal sustained commitment; seeing suffering doesn't guarantee ending it.

78. NASA/ESA - "Pillars of Creation" (Hubble Space Telescope) (1995/2014)

Location: Eagle Nebula, 6,500 light-years from Earth

Medium: Composite photograph from Hubble telescope

Towering columns of interstellar gas and dust where stars are born, cathedrals of creation 4-5 light-years tall. The most famous Hubble image, it appears on posters, T-shirts, album covers.

We're seeing the past (light took 6,500 years to reach us), and the pillars themselves may have already been destroyed by a supernova.

In 1995, Hubble Space Telescope photographed the Eagle Nebula's "Pillars of Creation"—three columns of molecular hydrogen and dust, each several light-years tall, where stars are forming. The image combined exposures from different wavelengths (visible and near-infrared) into a composite that made the invisible visible.

The pillars look like cosmic fingers reaching upward, or perhaps divine hands descending from heaven. The coloring (not "true" color but wavelengths mapped to visible spectrum) enhances drama, deep russet, gold, and teal. This is the universe's womb, stellar nursery where gravity compresses gas until nuclear fusion ignites and stars are born.

The image became astronomy's most iconic photograph, reproduced endlessly. It appears in textbooks, museums, homes worldwide, cosmic grandeur made accessible. People who can't name three constellations recognize the Pillars of Creation.

In 2014, Hubble re-photographed the pillars with better cameras, providing sharper detail and wider view. The new image shows stellar wind from young stars eroding the pillars, creation and destruction simultaneous, the universe's endless cycle visualized.

But here's the cosmic irony: in 2007, astronomers announced the pillars were probably destroyed 6,000 years ago by a supernova shockwave. Light from that destruction hasn't reached us yet, we're seeing the pillars as they were, not as they are. We're photographing ghosts, documenting structures that no longer exist.

This makes the image profoundly haunting: these majestic formations—among the universe's most beautiful sights, may be gone, and we won't know for another 1,000 years. We're seeing the past, celebrating beauty that's already ashes. Time and space conspire to make all cosmic photography elegiac.

The image also represents humanity's achievement: we built machines sophisticated enough to photograph the universe's infancy, to see what our eyes can't perceive, to travel mentally (if not physically) across cosmic distances that make our planet seem infinitesimal. This is visual technology at its apex, extending consciousness across light-years.

79. Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration - "First Image of a Black Hole" (April 10, 2019)

Location: M87 galaxy, 55 million light-years away

Medium: Radio telescope composite image

An orange ring surrounding darkness, the first photograph of a black hole's event horizon. This isn't a photograph in traditional sense; it's radio wave data translated into visible light image.

What we're seeing is light bent by gravity so intense that spacetime itself warps. The image proves Einstein's general relativity.

For decades, black holes were theoretical, mathematics predicting objects so dense that escape velocity exceeds light speed, creating regions where light cannot escape and therefore cannot be photographed. We inferred their existence through gravitational effects on surrounding matter, but couldn't image them directly.

In 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), a network of eight radio telescopes across the planet, effectively creating an Earth-sized telescope, synchronized observations of M87, a supermassive black hole 6.5 billion times the Sun's mass, 55 million light-years away.

They collected five petabytes of data (equivalent to 5,000 years of MP3 audio). Supercomputers processed it for two years, using algorithms to combine observations into a single image. The result: an orange ring (superheated matter orbiting the black hole) surrounding absolute darkness (the event horizon itself).

The image is both photograph and simulation, real data processed through complex algorithms to produce visual representation. What does a black hole "look like"? It looks like this, though our eyes could never see radio wavelengths. The image translates invisible data into visible form.

The orange glow is matter accelerated to nearly light speed, heated to billions of degrees, emitting radiation across the spectrum. The darkness at center is the event horizon, the boundary beyond which nothing escapes. Inside: physics breaks down, time stops, space curves infinitely. We can't see it; we can only see its absence.

The image proves Einstein's general relativity with unprecedented precision. The ring's size, shape, and brightness match theoretical predictions from equations written a century ago. Einstein described spacetime's curvature; EHT photographed it.

This represents science's triumph and limits simultaneously: we can photograph black holes 55 million light-years away, yet can't fully understand what happens inside them. We see evidence of reality but can't access reality itself. The image is both proof and mystery, it shows us what we predicted while reminding us how much remains unknown.

Katie Bouman, then 29-year-old computer scientist, led the algorithm development that made the image possible. Her joy at seeing the first results, captured in a photograph that went viral, reminded us that scientific achievement is human achievement, that wonder remains possible even when imaging the universe's most extreme objects.

80. Mars Rover - "Perseverance First Color Image from Mars" (February 2021)

Location: Jezero Crater, Mars

Medium: Digital photograph

Rocky Martian landscape in high definition, another planet's surface as intimate as Earth's. Humanity has sent cameras to Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, beyond the solar system.

These images expand consciousness: we're simultaneously here and there, seeing ourselves from elsewhere.

NASA's Perseverance rover landed on Mars February 18, 2021, equipped with 23 cameras (more than any previous Mars mission). Within days, it transmitted high-resolution color images showing Jezero Crater's rocky terrain, distant cliffs, and rust-colored sky.

The images are simultaneously alien and familiar: a desert landscape that could be Arizona or Nevada, except the sky is pink-orange (dust particles scattering sunlight differently than Earth's atmosphere), and the silence is absolute (Mars has no atmosphere to carry sound, until Perseverance's microphones captured wind noise, the first audio ever recorded on another planet).

We've sent cameras farther than humans can travel. Voyager 1, launched 1977, is now 14.5 billion miles from Earth, still transmitting images. We've photographed Jupiter's storms, Saturn's rings, Titan's methane lakes, Pluto's heart-shaped glacier, the solar system's edge. Our eyes have left the planet; our consciousness expands across cosmic distances.

This democratizes space exploration: anyone with internet can see Mars daily, watch rovers traverse alien landscapes, examine rocks from another world. Space isn't exclusive domain of astronauts, it's accessible to anyone with curiosity and connectivity.

But there's melancholy: we photograph other worlds while slowly destroying our own. Mars images show what Earth could become, a dead planet, once wet and possibly alive, now cold and barren. We search for ancient Martian life while driving current Earthly life toward extinction. The images are warning and aspiration simultaneously: escape might be possible, but prevention is preferable.

The Martian images also raise existential questions: Why do we photograph? We send robots millions of miles to take pictures no human will see in person. We document for documentation's sake, creating archives for hypothetical future audiences. Photography becomes less about witnessing and more about establishing record: we were here, we saw this, we existed.

81. James Webb Space Telescope - "Deep Field: The First Image" (July 12, 2022)

Location: Deep space (galaxies from 13.1 billion years ago)

Medium: Infrared composite photograph

The deepest image of the universe ever captured, thousands of galaxies, some from 13.1 billion years ago (400 million years after the Big Bang).

We're looking at light that travelled for most of the universe's existence. This image makes visible the previously invisible, showing us the infant universe. Each point of light is an entire galaxy containing billions of stars. The image redefines "deep time."

On July 12, 2022, NASA released the first deep-field image from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), humanity's most powerful space observatory. The image shows galaxy cluster SMACS 0723 as it appeared 4.6 billion years ago. But gravitational lensing, the cluster's mass bending spacetime, magnifies and distorts light from galaxies behind it, some from just 400 million years after the Big Bang.

The image contains thousands of galaxies, many never seen before. Each smudge, spiral, or point of light is billions of stars. The scale is incomprehensible: we're seeing galaxies that formed when the universe was 3% its current age, whose light traveled 13.1 billion years to reach us. Some of these galaxies may no longer exist, they've collided, merged, or dispersed in the eons since their light began its journey.

JWST observes in infrared wavelengths, seeing through cosmic dust that obscures visible light. This allows it to peer deeper into space and further back in time than any previous telescope. The universe's expansion redshifts ancient light, visible wavelengths stretched to infrared by cosmic expansion itself. JWST captures this stretched light, showing us the universe's childhood.

The image is composite, multiple exposures at different wavelengths, combined and color-coded for human perception. Like the black hole image, this isn't "true" color but wavelengths mapped to visible spectrum. We're seeing the invisible, translated into visual language our minds can process.

Every deep-field image, Hubble's, now JWST's, produces the same existential vertigo: we're infinitesimal. Our galaxy is one among billions. Our sun is unremarkable. Our planet barely exists at cosmic scale. Yet here we are, creating machines that can photograph the universe's infancy, consciousness contemplating its own cosmic context.

The image contains statistical certainty of extraterrestrial life: with billions of galaxies, each containing billions of stars, many with planets, the universe almost certainly contains other life. Yet we see no evidence—no signals, no visits, no contact. The Fermi Paradox visualized: all these galaxies, all this potential, yet we remain alone as far as we know.

JWST's images will continue for decades, each revealing more about the universe's structure, history, and fate. We're witnessing the universe witnessing itself—matter achieving consciousness and turning its attention backward through time, photographing its own origin story.

82. Sebastião Salgado - "Serra Pelada Gold Mine" (1986)

Location: Serra Pelada, Brazil

Medium: Gelatin silver print photograph

Thousands of mud-covered workers climb ladders out of a massive open-pit gold mine, biblical in scale, infernal in appearance. Salgado's photograph looks ancient (recalling Bruegel or Bosch) yet documents contemporary exploitation.

Critics accused him of aestheticizing suffering; he argues beauty is necessary to make people look at atrocity.

Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado documented Serra Pelada gold mine in 1986, during its peak operation. Fifty thousand miners (garimpeiros) worked in a single massive pit, carrying bags of mud up wooden ladders, hoping to find gold flecks worth a few dollars.

Salgado's photograph shows the pit from above: hundreds of mud-covered men climbing countless ladders, ant-like in their multitude, creating visual texture of human labor at overwhelming scale. The image recalls Renaissance paintings of Dante's Inferno, descending circles of suffering, humans reduced to insects, hell as economic system.

The aesthetic power is undeniable, the composition, the tonal range, the apocalyptic grandeur. Yet this beauty troubles critics: Does aesthetic achievement exploit the miners? Does making suffering beautiful make viewers consume rather than confront it? Can images this striking create change, or do they merely satisfy viewers' appetite for spectacular misery?

Salgado responds that beauty attracts attention suffering deserves. Ugly images are ignored; beautiful images demand viewing. If we must show exploitation, we should show it compellingly enough that people actually look. Beauty becomes ethical strategy, making the unwatchable watchable.

Serra Pelada closed in 1992, leaving environmental devastation and impoverished former miners. The gold extracted enriched brokers and dealers; the miners remain poor. Salgado's photographs are worth hundreds of thousands; the miners they depict remain anonymous, exploited, forgotten except as subjects in famous images.

This is documentary photography's persistent problem: the photographer gains fame documenting the powerless who remain powerless. The image circulates; the people remain trapped. Yet without documentation, their exploitation might be invisible. The contradiction has no resolution, only acknowledgment and ongoing ethical navigation.

83. Yann Arthus-Bertrand - "Heart of Voh" (Aerial Photography) (1990)

Location: New Caledonia

Medium: Aerial color photograph

A natural heart-shaped clearing in mangrove vegetation, photographed from above. Part of Arthus-Bertrand's "Earth from Above" project documenting the planet's beauty and fragility.

The image became an environmental icon, appearing on everything from UNESCO materials to Al Gore's presentations. It demonstrates that the most powerful images sometimes emerge from shifting perspective, literally seeing Earth from above changes how we understand our relationship to it.

French photographer Yann Arthus-Bertrand has spent decades photographing Earth from helicopters, documenting both beauty and environmental destruction. The “Heart of Voh”, a naturally occurring heart-shaped clearing in New Caledonian mangroves, became his most famous image.

The photograph is pure accident of nature: vegetation patterns creating recognizable shape that humans interpret as meaningful. The heart isn't designed or intentional, it's random pattern our brains recognize because we're pattern-recognition machines, finding meaning in chaos, seeing faces in clouds, hearts in vegetation.

Yet the image's power is real: it suggests Earth loves us, that nature contains affection, that our planet is worth cherishing. Environmental organizations adopted it precisely because it transforms ecological advocacy from duty into emotion, we should protect Earth not because we should but because we love it.

Aerial photography reveals patterns invisible from ground level. Arthus-Bertrand's "Earth from Above" project (started 1994) has photographed every continent, showing both sublime beauty (glaciers, forests, wildlife migrations) and catastrophic damage (deforestation, pollution, urbanization). The perspective shift creates psychological shift: from above, national borders vanish, human constructions seem temporary, Earth's systems reveal their interconnection.

The photograph also represents privileged perspective: aerial photography requires helicopters, fuel, money. Arthus-Bertrand can afford to photograph Earth from above; most humans experience it from ground level. The image is beautiful but also demonstrates inequality, who gets to see, who gets to photograph, whose perspective becomes "truth."

Still, the heart shape achieved its purpose: the image became universal symbol for environmental protection, circulating globally, inspiring campaigns, motivating action. Sometimes beauty matters more than critique; sometimes love motivates better than guilt.

84. Benin Bronzes (Photographed in British Museum) (16th-18th century bronzes, contemporary photographs)

Location: Benin City, Nigeria (origin); British Museum, London (current)

Medium: Bronze plaques; contemporary photograph

These aren't just objects, they're proof. When British forces looted thousands of bronze plaques from Benin City in 1897's "Punitive Expedition," Europeans couldn't believe Africans had created such sophisticated metalwork.

The photographs of these bronzes circulating globally demonstrate colonial theft and African artistic achievement simultaneously. Nigeria's campaign for repatriation makes these images politically charged: every photograph is evidence in an ongoing crime. The British Museum's refusal to return them (most remain in London) means the image of the bronzes, reproduced endlessly, becomes more accessible than the objects themselves.

In 1897, British forces invaded Benin City (in present-day Nigeria), ostensibly retaliating for the killing of a British delegation. The "Punitive Expedition" burned the city, killed thousands, and looted the Oba's palace. Among the plunder: thousands of bronze plaques, ivory carvings, and sculptures created between the 16th-18th centuries.

These Benin Bronzes demonstrated African artistic sophistication that contradicted European racist assumptions. The lost-wax bronze casting technique, the naturalistic portraiture, the historical documentation (the plaques showed courtly life, military campaigns, diplomatic meetings), all proved that African metallurgy and art rivaled European achievement.

Yet European museums treated them as ethnographic curiosities, proof of "primitive" cultures, not artistic masterpieces. Only gradually did recognition come that these were sophisticated historical records, artistic achievements, and cultural heritage unlawfully taken.

Nigeria has demanded repatriation for decades. Some institutions have returned bronzes; the British Museum refuses, citing its founding mandate to preserve world heritage. The irony: the museum claims to protect heritage it stole, arguing that returning objects to their origin would deprive the world of access.

But photographs have democratized access, anyone can Google "Benin Bronzes" and see high-resolution images. The digital reproductions are more accessible than the physical objects locked in London storage. In this sense, photography completes colonialism's work: stealing the objects, then photographing them, making images available while keeping originals captive.

Yet photographs also fuel repatriation campaigns: each image is evidence of theft, testimony to ongoing injustice, proof that these objects belong elsewhere. The photograph becomes tool for restoration, showing what was taken, demanding return, refusing to let colonialism's crimes fade into historical abstraction.

Contemporary artists like Fred Wilson and Kara Walker have created works using Benin Bronze imagery, questioning who owns cultural heritage, how museums perpetuate colonialism, whether images can replace objects. The question remains unresolved: do photographs of stolen artifacts mitigate or exacerbate the theft?

85. Liu Bolin - "Hiding in the City" Series (2005-present)

Location: Various locations, China and worldwide

Medium: Photograph (performance documentation)

Chinese artist Liu Bolin paints himself to blend perfectly into backgrounds, supermarket shelves, magazine racks, political posters, becoming invisible.

The photographs document performances critiquing consumerism, censorship, and individual erasure in contemporary China. After authorities demolished his Beijing studio in 2005, he began this series as protest. The images ask: How do we disappear? How does power render us invisible? In an age of surveillance and social media, invisibility becomes resistance.

Liu Bolin calls himself "The Invisible Man." Since 2005, he's created hundreds of photographs showing himself painted to match backgrounds, standing before shelves of merchandise, political posters, historical sites, corporate logos. From a distance, he vanishes; up close, his human form reveals itself.

Each photograph requires hours of preparation: positioning precisely, photographing the background, painting himself to match colors and patterns, remaining still for the final photograph. The result is simultaneously playful and disturbing, human reduced to pattern, individual erased by environment, person becoming product.

The series began when authorities demolished Liu's Beijing studio without notice. Powerless to stop them, he photographed himself camouflaged against the rubble, invisible protest, silent witness. The image asked: when the state destroys your space, do you disappear with it?

Subsequent works expanded the critique: painting himself before Tiananmen Square's portrait of Mao (the individual subsumed by political authority), before supermarket shelves (the person becoming commodity), before global brand logos (identity colonized by consumerism). Each disappearance is act of resistance through withdrawal, if they won't see us, we'll become unseeable.

The images resonate globally: how do we maintain individuality amid homogenizing forces? How do surveillance and algorithms make us disappear by reducing us to data? How does social media perform visibility while ensuring invisibility, millions seen, no one truly perceived?

Liu's invisibility is labor-intensive visibility, he works for hours to be unseen, photographs the unseeable, circulates images of absence. This paradox defines contemporary art: to critique invisibility, you must make invisibility visible; to resist being seen, you must be photographed.

86. Anonymous Ukrainian Citizens - "Destroyed Mariupol Theatre / 'CHILDREN' Written Outside" (March 2022)

Location: Mariupol, Ukraine

Medium: Satellite imagery, drone photographs

Russia's invasion of Ukraine becomes the most documented war in history. The Mariupol Drama Theatre, bombed despite "ДЕТИ" (CHILDREN) written in giant letters outside (visible from space), killed hundreds sheltering inside.

On March 16, 2022, Russian aircraft bombed Mariupol Drama Theatre where hundreds of civilians sheltered. Before the attack, survivors had painted "ДЕТИ" (Russian for "CHILDREN") in letters 10 meters tall on the ground outside, front and back of the building. The word was visible from space, captured by commercial satellites.

Despite this clear marking, the theatre was bombed. Estimated 300-600 people died, though exact numbers remain uncertain. Satellite images before and after show the building intact with clear CHILDREN markings, then destroyed with crater in center.

The images circulated instantly, satellite companies released photos within hours, Ukrainian citizens posted drone footage, survivors uploaded cellphone videos from the ruins. The documentation was overwhelming: we saw the markings, saw the destruction, saw the evidence of war crime unfold in near-real-time.

This is 21st-century warfare: totally documented, globally visible, instantly circulated. Unlike previous wars where military controlled information, Ukraine's war plays out across social media. Civilians with smartphones become war correspondents; commercial satellites provide intelligence; hackers leak communications; the fog of war lifts under illumination of ubiquitous cameras.

Yet documentation doesn't prevent atrocity. The word CHILDREN visible from space didn't protect the children inside. The satellite images, the videos, the global attention, none saved lives in the moment. Documentation creates evidence for eventual prosecution but offers no immediate protection.

The images raise questions: Does total visibility change warfare's nature? If everyone can see war crimes, are they less likely? Or does visibility without enforcement simply create archive of unpunished atrocities? We photograph everything yet seem powerless to stop anything.

The Mariupol Theatre images are evidence for potential war crimes trials. They'll be presented in courts, analyzed by investigators, used to assign responsibility. Images as legal evidence, photographs as testimony, satellites as witnesses—this is warfare's new reality. But justice delayed often becomes justice denied; documentation matters only if followed by accountability.

87. Kara Walker - "A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby" (2014)

Location: Domino Sugar Factory, Brooklyn (temporary installation)

Medium: Polystyrene-coated foam sculpture (photographed extensively)

A 75-foot-long sphinx-like figure with exaggerated African features, covered in white sugar, installed in an abandoned sugar refinery. Surrounding her: smaller attendant figures made of molasses-coated resin.

Walker's installation confronted slavery's economic foundation (sugar production), sexual exploitation, and mammy stereotypes. The sculpture existed for four months; photographs ensure its continued life. Visitors' selfies with the sculpture, often mocking it, became part of the work, documenting ongoing racism. The images reveal as much about viewers as the artwork itself.

In 2014, artist Kara Walker created "A Subtlety" for the Domino Sugar refinery in Brooklyn (scheduled for demolition). The monumental sculpture, a sphinx with Black woman's face, covered entirely in white sugar, dominated the space. Around her: fifteen smaller figures of young Black boys carrying baskets, made from sugar and molasses (many melted over the exhibition's duration).

The work's full title: "A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant." The title is deliberate mouthful, evoking 18th-century verbose exhibition labels while indicting sugar's role in slavery and exploitation.

The central figure combined sphinx (power, mystery, guardian), mammy figure (racist stereotype of asexual Black domestic). Covered in refined white sugar, the product of enslaved labor, she was simultaneously monument and accusation.

Visitors' responses became part of the artwork: thousands posed for selfies, many mocking the sculpture. Walker documented these interactions, showing how contemporary audiences reenact historical racism under guise of artistic appreciation.

The photographs of the installation, both professional documentation and visitors' selfies, circulated far more widely than the temporary sculpture itself. The work existed for 16 weeks; the images exist indefinitely. In this sense, photography completes the artwork, preserving it while documenting audience complicity.

The smaller figures' melting was intended, sugar and molasses couldn't withstand summer heat. They dissolved slowly, creating sticky residue, sweetness decaying into stickiness. This physical transformation literalized slavery's ongoing legacy: sweet products requiring bitter labor, exploitation's residue persisting long after the system "ended."

88. Zanele Muholi - "Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail the Dark Lioness)" Series (2012-present)

Location: Various locations globally

Medium: Black-and-white self-portrait photographs

South African visual activist Zanele Muholi creates self-portraits celebrating Black lesbian identity and confronting South Africa's violence against LGBTQ+ people.

Using dramatic lighting and props, Muholi transforms themselves into various characters while maintaining intense direct gaze. The title translates as “Hail the Dark Lioness”, a reclamation of Blackness and queer identity. These images counter both apartheid's visual legacy and contemporary homophobia, asserting: "I exist. I am visible. I am beautiful."

Zanele Muholi (who uses they/them pronouns) began "Somnyama Ngonyama" in 2012, creating over 365 self-portraits (one for each day of the year, though the series continues). Each photograph shows Muholi with props and costumes, rubber gloves, plastic bags, clothespins, wire, kitchen implements, transforming everyday objects into regal adornments or confrontational statements.

The photographs are high-contrast black-and-white, Muholi's skin rendered so dark it approaches absolute black. This aesthetic choice is deliberate: reclaiming Blackness against colorism and racism, making Blackness hypervisible against white supremacy's attempt to render Black people invisible or inferior.

Muholi's direct gaze is uncompromising, they look at viewers with intensity that demands recognition. These aren't passive portraits; they're confrontations. Each image insists: I am here, I am Black, I am queer, I am beautiful, and I will not look away.

The series responds to South Africa's contradictions: the country has progressive constitution protecting LGBTQ+ rights while experiencing epidemic violence against queer people (particularly Black lesbians). Muholi's work is survival strategy and resistance, making themselves hypervisible as defense against erasure.

The props often reference labor, domesticity, and control: rubber gloves (domestic work), clothespins (restraint and pain), plastic bags (suffocation and consumption). These everyday objects carry histories of exploitation while being transformed into aesthetic statements, beauty extracted from oppression, dignity claimed amid indignity.

Muholi describes themselves as "visual activist" rather than artist, the distinction matters. These photographs aren't just aesthetic objects but political interventions. They document existence, claim space, refuse invisibility, and insist on recognition for communities systematically marginalized.

The series photographs circulate globally, museums, galleries, publications, social media, ensuring visibility far beyond Muholi's physical presence. Each image multiplies through reproduction, reaching audiences who might never encounter Black queer South African experiences otherwise. Photography becomes testimony, circulation becomes survival.

89. Omar Victor Diop - "Diaspora" Series (2014)

Location: Studio photographs, Dakar, Senegal

Medium: Color photography

Senegalese photographer Omar Victor Diop inserts himself into recreations of European portraiture, wearing period costumes while holding a football (soccer ball), a symbol of contemporary African diaspora and migration.

Each portrait references a historical Black European figure (entertainers, intellectuals, nobility) who have been erased from dominant historical narratives. The anachronistic football asks: How do we remember? Who gets portrayed? The images challenge both European art history's whiteness and contemporary stereotypes about African identity.

Omar Victor Diop's "Diaspora" series recreates European portraits of Black subjects from the Renaissance through 19th century, people who lived in Europe, achieved prominence, yet disappeared from historical memory. Each photograph shows Diop in period-accurate costume, posed like the original, but holding a modern football.

The subjects include: Angelo Soliman (18th-century African prince enslaved then freed, became prominent Viennese intellectual); Joseph Boulogne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges (18th-century violinist and composer); Alessandro de' Medici, Duke of Florence (16th-century ruler of African descent); and others, Black Europeans whose stories were suppressed or forgotten.

The football is provocative anachronism: contemporary African diaspora experiences, migration patterns, and stereotypes compressed into single prop. Football represents African athletic excellence while also reducing African identity to physical prowess, the complexity intentional. Diop asks: Do we remember these historical figures, or only acknowledge African presence when it confirms contemporary stereotypes?

The series challenges art history's racial erasure. European museums display Renaissance and Baroque art without acknowledging that Africa and Europe had continuous contact, that Black people lived in European courts, that racial categories weren't as rigid as later colonialism enforced. These portraits restore historical complexity.

Diop's insertion of himself (Senegalese photographer, 21st century) into historical European portraits also questions representation's politics: Who gets to tell history? African artist reclaiming African stories erased by European narratives—this is visual decolonization, taking control of historical memory through photographic reimagining.

The images circulate on social media and in galleries, reaching diverse audiences. They function as education (revealing forgotten histories), critique (challenging dominant narratives), and celebration (honoring Black European achievement). Photography becomes historical correction, aesthetic pleasure, and political intervention simultaneously.

90. JR - "Women Are Heroes" / Favela Eye Installation (2008-2009)

Location: Favela Morro da Providência, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Medium: Large-scale photographic paste-ups on buildings

French artist JR photographed women's eyes in Rio's favelas, then wheat-pasted giant prints onto houses and staircases. The installation transformed the shantytown into a gallery, making invisible residents visible at monumental scale.

These eyes stare back at the city that ignores them. Photographed from above (the only way to see the full composition), the images went viral, forcing global attention on favela residents. When police attempted to raid the community, the giant eyes bore witness, surveillance reversed, the watched watching back.

JR, anonymous French street artist (always photographed wearing sunglasses and hat), created "Women Are Heroes" project across multiple continents, celebrating women in communities experiencing violence and poverty. In Rio's Morro da Providência favela (2008), he photographed women's eyes, close-ups showing only eyes and surrounding skin, then printed them at massive scale on vinyl and wheat-pasted them on favela buildings.

The effect was transformative: houses became faces, staircases became compositions, the entire favela became artwork visible across Rio. From ground level, you saw giant eyes everywhere, on roofs, walls, steps. From above (helicopter or drone), the eyes assembled into coherent patterns, creating images visible only from privileged aerial perspective inaccessible to residents.

This reversal of surveillance is crucial: wealthy Rio neighborhoods use helicopters; favela residents are watched from above by police, military, media. JR's installation turns this dynamic around, now the favela watches back, giant eyes staring at the city that marginalizes these communities.

The women photographed aren't named in the artworks, hey become universal through anonymity, "Women Are Heroes" rather than specific individuals. This choice is both problematic (erasing individual agency) and strategic (creating collective symbol). The images represent all favela residents resisting invisibility.

When police raided the favela during the installation's presence, the giant eyes witnessed, creating uncanny experience where the watched became watchers. The photographs don't prevent violence but they document, testify, refuse to let atrocities happen unobserved.

JR's work is temporary, weather and time destroy the paste-ups. But photographs of the installations circulate indefinitely, reaching global audiences, generating media attention, bringing resources to communities. The physical artwork disappears; the images remain. Photography completes street art's impact by giving it circulation beyond its physical location.

The project raises questions about artistic intervention: Is JR helping by bringing visibility, or is he exploiting poverty for artistic reputation? He works collaboratively with communities, seeking permission, sharing images with participants. Yet he gains international fame while residents remain poor. The tension between good intentions and persistent inequality has no easy resolution.

91. Trevor Paglen - "They Watch the Moon" (2010)

Location: Photographed from Earth (classified spy satellite in orbit)

Medium: C-print photograph

Artist Trevor Paglen photographs classified US spy satellites in orbit—tiny dots against the stars. These "blank" images reveal the surveillance infrastructure watching us.

Paglen makes the invisible visible: government secrets, classified projects, drones, NSA facilities. His work asks: What images exist that we're not allowed to see? Who controls visibility? In an age of total surveillance, what does it mean to photograph the watchers?

Trevor Paglen, artist and geographer, has spent decades photographing things designed to remain unseen: classified military bases in remote deserts, underwater submarine cables, CIA rendition aircraft, and, most ambitiously, classified surveillance satellites.

These satellites orbit Earth continuously, photographing ground activities with resolution allegedly sufficient to read license plates from space. Their existence is acknowledged but details are classified. Paglen tracks them using amateur satellite-watching networks (astronomy enthusiasts who catalog orbital objects), calculates positions, then uses telescopes with long-exposure photography to capture them as they pass.

The resulting images are “almost nothing”, tiny streaks or dots against stars. They're barely visible, often requiring explanation to understand what you're seeing. Yet they're profound testimony: these are machines watching us from space, and here's proof they exist.

Paglen's work inverts surveillance: if they watch us, we'll watch them. If governments classify their watching mechanisms, we'll declassify through photography. His images make visible the invisible infrastructure of state power, surveillance transformed from abstract concept to concrete (if barely visible) reality.

The aesthetic is important: these images are beautiful, long exposures capture star trails, satellites appear as geometric tracks across night sky, the universe's grandeur frames state surveillance apparatus. Beauty makes surveillance visible; sublimity makes secrecy unbearable.

Paglen's work also questions photography's epistemological status: what constitutes evidence? These images require extensive explanation, without caption, they're meaningless dots. The photograph alone proves nothing; combined with context, it reveals everything. This demonstrates that images never speak for themselves, meaning emerges from captioning, framing, interpretation.

In an era of ubiquitous surveillance (street cameras, facial recognition, data tracking, satellite monitoring), Paglen's work insists on counter-surveillance: watching the watchers, photographing the photographers, making visible the mechanisms of visibility. If surveillance is mutual, power relationships shift—slightly, insufficiently, but potentially significantly.

92. Forensic Architecture - "The Killing of Mark Duggan" (3D Reconstruction) (2015)

Location: Digital reconstruction (incident occurred Tottenham, London, 2011)

Medium: 3D architectural modeling, video analysis

Research group Forensic Architecture uses video footage, photographs, and testimony to create precise 3D reconstructions of human rights violations.

Their investigation of Mark Duggan's killing by London police (which sparked 2011 riots) challenged official narratives. This represents a new image category: evidence-as-art, where multiple fragmentary images are synthesized into spatial truth. The work influenced the inquest verdict. Images as forensic tools; architecture as witness; evidence as advocacy.

Forensic Architecture, research group based at Goldsmiths, University of London (led by architect Eyal Weizman), investigates human rights violations using architectural analysis, 3D modeling, video analysis, and testimony synthesis. Their work exists at the intersection of art, activism, and legal evidence.

For Mark Duggan's case: London police shot Duggan (29, Black British) on August 4, 2011, claiming he was armed and posed threat. His death sparked Tottenham riots, spreading across England. Official investigation found the shooting lawful; family contested this.

Forensic Architecture gathered all available evidence: CCTV footage, witness testimony, photographs, police statements, ballistic reports. They identified contradictions: police claimed Duggan pointed gun; witnesses said his hands were empty; gun found 20 feet away behind a fence (thrown? planted?).

Using 3D modeling software, they reconstructed the scene spatially, synchronizing video timelines, testing sight lines, analyzing bullet trajectories. The resulting animation shows what probably happened, and reveals impossibilities in official narrative. If Duggan was holding gun as police claimed, how did it land 20 feet away? The physics don't match testimony.

Their analysis was submitted to the inquest. While the verdict remained "lawful killing," the evidence complicated official narratives, forced additional scrutiny, demonstrated police testimony's inconsistencies. Images became legal argument, 3D reconstructions carrying evidential weight in court.

This represents profound shift: images aren't just documentation but analytical tools. By synthesizing fragmentary evidence (multiple cameras, angles, timestamps) into unified spatial model, Forensic Architecture creates images that never existed, composites revealing truth no single camera captured.

Their work has investigated: Israeli Defense Forces killing Palestinian civilians, Syrian and Russian bombing of hospitals, police violence globally, environmental destruction. Each investigation produces images, 3D animations, annotated videos, spatial reconstructions, that function as evidence while being exhibited as art.

This challenges categories: Is this architecture? Art? Activism? Legal evidence? It's all simultaneously, interdisciplinary practice using aesthetic means toward political ends. The images are beautiful (sophisticated graphics, elegant animations) and devastating (documenting murder, torture, war crimes).

Forensic Architecture demonstrates that in an age of ubiquitous cameras, the problem isn't lack of documentation but synthesis of fragmentary evidence. Their work shows how to transform proliferating images into coherent narratives that demand accountability.

93. Mona Chalabi - "Data Visualization as Image" (Refugee Statistics) (2015-present)

Location: Published across media platforms

Medium: Hand-drawn data visualizations

Iraqi-British data journalist Mona Chalabi transforms statistics into hand-drawn illustrations that make abstract numbers human.

Her visualization of refugee statistics shows each person as a small figure, making "70 million displaced people" comprehensible. In an era of information overload, her work demonstrates that the most powerful images sometimes come from making data feel rather than just inform. She turns numbers into narratives, statistics into faces. This is a new category of powerful image: the infographic as witness.

Mona Chalabi, data journalist at The Guardian and illustrator, creates hand-drawn data visualizations that transform statistics into accessible, human-scale narratives. Unlike typical infographics (clean, digital, abstract), Chalabi's illustrations are deliberately imperfect, wobbly lines, hand-drawn figures, annotations in casual handwriting.

For refugee statistics: instead of abstract bar chart showing "70.8 million displaced people," she draws 70.8 million tiny figures, page after page of small human shapes, making the number viscerally comprehensible. You can't process 70 million abstractly, but you can see pages full of humans and begin to grasp scale.

Her work addresses fundamental problem: statistics are alienating. "12% of women experience sexual assault" is abstract; drawing 12 of 100 female figures with trauma indicators makes it concrete. Numbers distance us from human cost; Chalabi's illustrations restore human scale.

The hand-drawn aesthetic is strategic: it makes data feel accessible, personal, intimate. Digital perfection suggests authority but creates distance; imperfect human handwriting suggests conversation rather than lecture. Chalabi draws you into statistics rather than presenting them from above.

She's created visualizations for: refugee populations, COVID-19 deaths, gender pay gaps, police violence statistics, menstruation data. Each transforms abstract numbers into narratives with human implications. The images circulate on social media, reaching audiences who ignore traditional data presentations.

This represents new category of powerful image: data visualization as emotional witness. Chalabi demonstrates that information isn't just about accuracy but about accessibility, that truth requires empathy as much as precision, that the most ethical way to present statistics about humans is to keep the humans visible within the numbers.

Her work challenges objectivity's myth: all data visualization makes choices about what to emphasize, how to frame, what to make visible. By making her choices transparent (hand-drawn, annotated, openly subjective), Chalabi reveals what slick digital infographics hide: perspective, interpretation, values.

In an age of data overload, where statistics proliferate but understanding diminishes, Chalabi shows that sometimes the most powerful way to communicate truth is through deliberately imperfect, obviously human images that refuse to let numbers erase people.

94. Anonymous - "George Floyd Mural, Minneapolis" (May-June 2020)

Location: 38th Street and Chicago Avenue, Minneapolis (and hundreds of locations globally)

Medium: Street mural (photographed)

After George Floyd's murder by police (May 25, 2020), street murals appeared globally within days, Minneapolis, Berlin, Nairobi, Sydney.

The image of Floyd, often his face with the words “I Can't Breathe”, became 2020's most powerful icon. These murals turned city walls into memorials, protest into public art. The photographs of these murals (shared millions of times) amplified the message: Black Lives Matter. The decentralized, anonymous, viral nature of these images represents 21st-century visual activism, anyone can create an image, everyone can distribute it.

On May 25, 2020, Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd by kneeling on his neck for 9 minutes and 29 seconds. Bystanders filmed the murder on smartphones; the videos went viral immediately. Within 24 hours, protests erupted; within days, murals appeared.

At the intersection where Floyd was killed (38th and Chicago), artists created memorial murals, Floyd's face, quotes, flowers, demands for justice. The location became sacred space, shrine, and protest site simultaneously. Similar murals appeared globally: Berlin, London, Nairobi, Sydney, Mexico City. Artists created variations, some photorealistic, others stylized, some with angel wings, others with clenched fists.

The decentralized creation is significant: no single artist, organization, or authority coordinated this. The image emerged organically, reproduced virally, adapted locally. Street artists, activists, and community members created murals without permission, transforming public spaces into testimony.

“I Can't Breathe”, Floyd's repeated plea as Chauvin murdered him, became the movement's text. The words appeared on murals alongside his face, compressing his murder into image and slogan. This is contemporary visual activism: image plus text, face plus message, memorial plus demand.

The murals' photographs circulated more widely than the murals themselves. Most people saw Floyd's mural-image through social media rather than in person. Photography extended the murals' impact globally, making local testimony into international symbol.

The murals function at multiple levels: memorial (honoring Floyd), protest (demanding justice), art (beautifying grief), and political demand (Black Lives Matter). They're simultaneously personal (expressing loss) and collective (representing systemic racism). Individual creations that become collective movement.

Some murals were vandalized; others were protected by communities; many were painted over after months; photographs preserve them all. The physical murals are temporary; the photographed murals are permanent. Digital circulation ensures that even destroyed murals continue witnessing.

This is 21st-century memorial practice: decentralized, viral, visual. The images don't just document protests, they ARE the protest, circulating globally, mobilizing solidarity, making invisible violence undeniably visible.

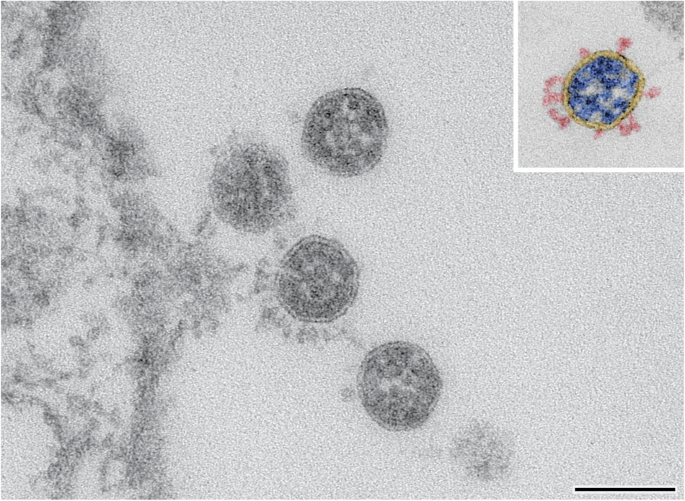

95. COVID-19 Visualization - "Coronavirus Under Electron Microscope" (February 2020)

Location: Rocky Mountain Laboratories, Montana

Medium: Colorized transmission electron micrograph

The virus that shut down the world, made visible. Orange spike proteins protrude from grey viral particles, beautiful and terrifying.

This image appeared everywhere: news broadcasts, scientific papers, public health posters. Making the invisible enemy visible didn't diminish its power but helped us comprehend the incomprehensible. Compare to medieval plague imagery: we can now photograph our destroyer at 25,000x magnification. The image is simultaneously proof of scientific advancement and reminder of nature's indifference.

When COVID-19 emerged (late 2019-early 2020), it was invisible threat, microscopic virus spreading asymptomatically, killing unpredictably. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) at Rocky Mountain Laboratories used electron microscopy to photograph SARS-CoV-2 virus particles.

The resulting images showed viral structure: spherical core covered in spike proteins (giving coronavirus its name, "corona" meaning crown). The images were colorized (electron microscopes don't capture color, scientists add it for clarity and visual appeal), typically orange or red spikes against grey or blue backgrounds.

These images became the pandemic's face. Every news report, every article, every public health poster showed coronavirus images. The virus that was killing millions became icon, recognized globally, reproduced endlessly, feared universally.

Making the invisible visible served multiple functions: scientific (understanding viral structure aids vaccine development), psychological (humans fear the unknown less than the unseen, visualization reduces existential dread), and communicative (a visible enemy can be fought; abstraction paralyzes).

Yet the images are also aesthetically striking, almost beautiful. The spike proteins create geometric patterns; the spherical symmetry is elegant; the colorization is vivid. This beauty is disturbing: our destroyer is photogenic. Nature's indifference to our suffering is literally visible, the virus isn't malicious, just efficient.

Compare to medieval plague imagery: they personified death as skeleton, made invisible disease into visible monster. We do the same, but scientifically, electron microscopy instead of religious allegory. Both attempts serve similar purpose: making comprehensible what terrifies through its incomprehensibility.

The coronavirus images also became memes, parodies, artistic inspiration. The image circulated so ubiquitously it became abstracted, people forgot these photographs show actual virus particles that killed millions. Familiarity bred not contempt but numbing, the image that should horrify became wallpaper.

This is pandemic-era visual culture: ubiquitous scientific imagery,

constant exposure, meaning diluted through repetition. The most significant biological threat in a century becomes just another image in the feed, scrolled past, barely noticed, endlessly reproducible.

96. Digital Artists - "NFT as Image: Beeple's 'Everydays: The First 5000 Days'" (2021)

Location: Digital/blockchain

Medium: Digital collage (NFT - non-fungible token)

A collage of 5,000 daily digital artworks sold for $69 million, making Beeple the third-most valuable living artist.

This isn't important because it's good (it's not particularly); it's important because it represents a paradigm shift: digital scarcity, blockchain as authenticity, ownership divorced from possession. You can view the image for free online, but one person "owns" it via NFT. This challenges everything we thought we knew about images: copying, value, originality. It's either art's future or an elaborate scam, possibly both.

In March 2021, Christie's auction house sold Beeple's (Mike Winkelmann) "Everydays: The First 5000 Days" for $69.3 million. The artwork: a collage of 5,000 digital images Beeple had created daily since May 2007, crude, provocative, often grotesque digital art ranging from political satire to sci-fi imagery to pop culture mashups.

The sale wasn't of a physical object but an NFT (non-fungible token), blockchain record establishing ownership of the digital file. Anyone can view, copy, or download the image; but only one person "owns" it via blockchain verification.

This challenges fundamental assumptions about art: scarcity creates value, but digital files are infinitely reproducible. NFTs solve this (or claim to) by creating artificial scarcity through blockchain, not controlling access but establishing provenance. You don't own exclusive viewing rights; you own the "original" even though digital files have no originals.

Critics call NFTs absurd: paying millions for what anyone can screenshot is paying for nothing. Supporters argue NFTs revolutionize art: artists control distribution, collectors prove authenticity, middlemen are eliminated (except platforms taking percentage).

The $69 million sale validated NFTs as art market category while revealing their absurdity. Beeple's work isn't particularly innovative, the value comes from novelty (first major NFT auction) and speculation (crypto investors proving blockchain's legitimacy).

The environmental cost is staggering: NFTs on Ethereum blockchain (before the merge to proof-of-stake) consumed enormous energy, estimates suggested individual NFT transactions used energy equivalent to month of household electricity. Digital scarcity achieved through environmental destruction.

Beeple's sale triggered NFT frenzy: celebrity NFTs, profile picture projects (Bored Ape Yacht Club, CryptoPunks), digital land sales, virtual fashion. The market peaked in 2021-2022, then crashed, many NFTs now worth fraction of purchase price, some worthless.

The phenomenon reveals 21st-century economics: value is consensus, ownership is abstract, images are assets. NFTs demonstrate that in digital age, scarcity is constructed not natural, and humans will pay for anything if enough others agree it's valuable.

Whether NFTs are art's future or temporary bubble remains uncertain. But they've permanently changed discourse: images aren't just aesthetic objects or documentation, they're tradable assets, financial instruments, speculative investments. The image has become currency.

97. Instagram / Social Media - "The Egg (World Record Egg)" (January 4, 2019)

Location: Instagram

Medium: Digital photograph

A simple photograph of a brown egg on a white background, posted to Instagram with the caption "Let's set a world record together and get the most liked post on Instagram."

It succeeded, surpassing Kylie Jenner's previous record with 55+ million likes. This is the ultimate anti-image image: it means nothing, represents nothing, yet became the most liked photograph in Instagram history. It's a Duchampian gesture for the social media age, a readymade achieving fame through collective agreement. The image proves that in the 21st century, virality itself creates meaning.

On January 4, 2019, account @world_record_egg posted a stock photograph of an ordinary brown egg with simple challenge: break the Instagram like record (then held by Kylie Jenner's pregnancy announcement photo at 18 million likes).

The internet responded enthusiastically. Within days, the egg had tens of millions of likes. Within weeks, it surpassed Jenner, eventually reaching 55+ million likes (current count varies as Instagram hides exact totals).

The creator, Chris Godfrey (British advertising creative), explained it as social experiment: "Let's build something positive together that's not driven by celebrities or influencers." But the gesture is more complex, it simultaneously mocks and participates in Instagram's attention economy.

The egg is perfect anti-content: it's not beautiful, interesting, or meaningful. It's generic stock photography, the kind of image everyone ignores. Yet it became Instagram's most liked post because collective action created value from nothing. The image matters because we agreed it matters; it's famous because it's famous.

This is Duchampian gesture for digital age: Duchamp's urinal challenged what could be art; the egg challenges what merits attention. Both assert that context creates meaning, gallery transforms urinal into art; viral consensus transforms egg into icon.

The egg also critiques influencer culture: Jenner's photo was peak celebrity narcissism (announcing pregnancy to monetize family drama). The egg was collective joke, millions preferring ordinary object to celebrity. The victory was brief (Jenner has since regained top spot), but point was made: attention is arbitrary, fame is collective delusion, and the internet prefers absurdist humor to manufactured celebrity.

After achieving the record, @world_record_egg posted follow-up: the egg cracking under pressure, revealing mental health message. The account attempted to transform joke into advocacy, using viral attention for social good. Whether this succeeded or simply extended the gag remains debatable.

The egg demonstrates social media's logic: virality is self-perpetuating (people like because others liked), meaning is negotiable (we assign significance through collective attention), and images are currency (likes are social capital). In this economy, the most meaningless image can become the most valuable.

98. Malala Yousafzai - "The Girl Who Was Shot" (2012-present)

Location: Pakistan, UK, global

Medium: News photography, portraiture

Malala Yousafzai, shot by Taliban for advocating girls' education, became global icon through photographs: as injured girl, as UN speaker, as Nobel laureate.

No single image dominates, but the accumulation of images, girl with headscarf, speaking to world leaders, holding her Nobel Prize, creates a narrative arc of resilience. This represents how contemporary image power works: not one decisive photograph but a stream of images across media platforms building into collective memory.

On October 9, 2012, Taliban gunman shot 15-year-old Malala Yousafzai in Pakistan's Swat Valley for advocating girls' education. She survived, recovered in UK, and became global symbol for education rights.

Unlike previous entries where single image defines a moment, Malala's story is told through accumulating photographs: lying in hospital bed, addressing UN, meeting world leaders, receiving Nobel Peace Prize (at 17, the youngest laureate), graduating from Oxford, marrying, advocating globally.

This photographic stream creates biographical narrative: victim becoming survivor, girl becoming woman, local activist becoming global figure. Each photograph adds to mythology: Malala the brave, the brilliant, the determined, the inspiring.

The images function ideologically: they show education's power to transform lives, women's capacity for leadership, activism's effectiveness. But they also simplify, Malala becomes symbol, losing complexity. She's inspiration but also industry: books, films, Malala Fund, speaking tours. The images circulate partly because they're profitable.

There's also geopolitical dimension: Western media loves Malala's story because it confirms assumptions about Islam's oppression and Western values' superiority. She's weaponized for cultural narratives: Muslim girl saved by West, education triumphing over extremism, modernity defeating tradition.

Malala herself navigates this carefully: using platform for advocacy while resisting being reduced to symbol. She critiques drone strikes, supports Palestinian rights, questions Western military interventions, complicating the simple narrative her images suggest.

Contemporary image power works differently than historical precedents: instead of one iconic photograph, we have Instagram feeds, documentary films, news coverage, selfies with politicians. The image stream creates persona, curated, managed, distributed across platforms.

Malala's photographs represent 21st-century celebrity activism: image and advocacy inseparable, personal story as political tool, social media as organizing platform. The photographs aren't just documentation, they're activist strategy, creating recognition that enables influence.

99. Climate Change - "Amazon Rainforest Burning (Satellite Imagery)" (August 2019)

Location: Amazon Basin, Brazil

Medium: Satellite photography

Satellite images show smoke from Amazon fires visible from space, darkening São Paulo's sky. These images made abstract climate change tangible,the Earth's lungs burning while satellites watch.

Shared globally, they pressured Brazilian government, mobilized protests, and demonstrated satellite imagery's power as environmental witness. We can now see planetary-scale destruction in real-time. The images ask: Who watches? Who acts? Who is accountable when the crimes are visible from space?

In August 2019, fires in Amazon rainforest intensified dramatically, 72,843 fires detected by satellites, 83% increase over previous year. NASA and European Space Agency satellites photographed smoke plumes visible from space, covering thousands of square kilometers.

São Paulo, 2,000+ miles from fires, experienced daytime darkness as smoke blocked sunlight. Residents posted photographs: midday darkness, orange sky, ash falling. The images went viral, tangible evidence that environmental destruction affects everyone, not just distant ecosystems.

Satellite images revealed fire distribution: concentrated in deforested areas, aligned with roads and property boundaries, clear evidence of intentional burning for agriculture. These weren't natural wildfires but deliberate forest destruction, visible from space, documented continuously.

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro initially denied severity, dismissed data as lies, suggested NGOs set fires to discredit his government. But satellite images made denial impossible, international pressure mounted, celebrities amplified messages, protests erupted globally.

The images represent new form of environmental monitoring: continuous satellite surveillance makes large-scale destruction undeniable. Before satellites, deforestation happened invisibly; now it's documented in real-time. Transparency doesn't guarantee prevention, but it complicates impunity.

Yet satellite images are double-edged: they reveal destruction while reinforcing imperial surveillance. Space technology is expensive—few nations have it. The Global North photographs Global South's environmental destruction, often ignoring its own. Satellites see Amazon fires while missing developed nations' carbon emissions, industrial pollution, consumption patterns that drive deforestation.

The Amazon images also show documentation's limits: we saw fires, shared outrage, demanded action. Then attention moved elsewhere. The feed scrolled on; new crises emerged; the Amazon continued burning. Images create temporary awareness, but without sustained political will, awareness evaporates.

Climate change is inherently difficult to photograph—it's gradual, diffuse, statistical. Fires, floods, hurricanes provide dramatic visuals, but slow temperature rise, ocean acidification, biodiversity loss resist visualization. We need images for mobilization, but climate's worst effects escape the frame.

The Amazon images matter despite limitations: they made climate crisis visible at planetary scale, demonstrated satellite technology's advocacy potential, and proved that some environmental crimes are now impossible to hide. Whether visibility translates to action remains uncertain, but visibility is precondition for accountability.

100. Aboriginal Dreamtime Art - "Wandjina Rock Art (Continuous Tradition)" (4,000+ years ago to present)

Location: Kimberley region, Western Australia

Medium: Ochre on rock; modern acrylic on canvas

Wandjina spirits, cloud and rain beings with large eyes, no mouths, halos around heads—painted on rock shelters across the Kimberley. Unlike "prehistoric" cave art that ceased millennia ago, Wandjina paintings are living images, regularly repainted by Aboriginal custodians maintaining 60,000+ years of continuous cultural practice.

These aren't museum pieces, they're active religious images with ongoing spiritual power. To photograph them without permission is sacrilege; to reproduce them commercially is theft. This final image in our compendium reminds us: not all powerful images belong to everyone. Some images hold power precisely because they resist commodification, circulation, global access.

The oldest continuous living culture on Earth has been making powerful images for 65,000 years, longer than any civilization in this list. Aboriginal Australian art predates Egyptian, Sumerian, Chinese, Indus Valley civilizations combined. The beginning and the end of our journey are the same people, still creating, still painting the Dreaming.

We end where we began, not in European caves but in Australian rock shelters, where image-making tradition has never ceased. While other civilizations rose and fell, Aboriginal peoples maintained unbroken artistic practice spanning Ice Ages, rising seas, continental transformations, and colonial devastation.

Wandjina are ancestral beings from the Dreamtime (Dreaming), the eternal time when ancestral spirits created the land, established laws, formed features. They're associated with water, clouds, rain, fertility. Depicted with large eyes (watching everything), no mouths (too powerful to speak, words would destroy), and halos (representing cloud or rainbow).

The images are sacred, not decorative but religiously significant. They're maintained through repainting: custodian families refresh images using traditional methods (ochre, charcoal), ensuring continuity across generations. Some rock art sites have been repainted for thousands of years, each generation adding layer while respecting earlier work.

This repainting practice challenges Western art concepts: original versus copy, preservation versus transformation, artist versus tradition. Wandjina aren't "authored" by individuals, they're collective ongoing creation, tradition-bearers adding to what ancestors began. The "authentic" image isn't original painting but continuous practice.

Aboriginal custodians restrict Wandjina reproduction: photographing requires permission; commercial use is forbidden. This isn't primitive superstition but sophisticated cultural property protection. Wandjina images embody spiritual power, inappropriate reproduction is spiritual violence, not just copyright infringement.

Yet Wandjina appear in Western museums, textbooks, tourist merchandise, often without permission. This theft continues colonialism's pattern: taking Aboriginal land, children, culture, now sacred images. The images circulate globally while custodians remain marginalized, impoverished, fighting to protect what colonialism hasn't yet stolen.

We end here deliberately: after 73,000 years of human image-making, after Renaissance masters and Enlightenment revolutions, after photography and cinema and digital ubiquity, we return to tradition that predates and outlasts everything else. The oldest continuous image-making practice reminds us that images aren't just about circulation, reproduction, and access, they're about sacred relationship, communal responsibility, and respect for power we don't fully understand.

Wandjina watch us watching them. Their large eyes see everything, colonial theft, tourist cameras, digital reproduction. They remind us that before images became currency, before they became infinite, before they became everything, they were sacred. Some still are.

After the Infinite Scroll

Seventy-three thousand years from Blombos Cave to Instagram. From ochre handprints to NFTs. From singular paintings viewed by firelight to 95 million photographs uploaded daily.

The 21st century didn't just accelerate image-making, it fundamentally transformed what images are. We've reached image totality: more images created today than in all previous centuries combined. The quantitative became qualitative. The boundary between image and reality dissolved entirely.

We are the first generation that cannot look away. The eternal gaze became the infinite scroll. Images pursue us, notifications, surveillance, feeds endlessly refreshing. We photograph everything while witnessing nothing. We document moments we're too distracted to experience. We're drowning in images while starving for meaning.

Yet resistance persists: Aboriginal Dreamtime art refuses commodification after 60,000 years. Forensic Architecture transforms fragmented images into irrefutable evidence. Climate activists weaponize satellites against governmental denial.

These images refuse to be mere content. They remember that images once had power because they were rare, sacred, consequential, and insist that even in an age of image infinity, some images still can be.

The choice before us: one path leads to total mediation, every surface a screen, every moment archived, reality fully replaced by simulation. The other path retrieves images' power through intention, creating less, seeing more; protecting the sacred; demanding accountability; choosing deliberately what deserves our gaze.