The Neuroscience of Curiosity: How Your Brain Learns Through Wonder

Thu Dec 25 2025

Discover how curiosity activates your brain's reward system, enhances memory through dopamine release, and transforms learning. Learn the latest neuroscience research on curiosity and practical applications for education and personal growth.

Understanding the Brain's Most Powerful Learning Mechanism

What makes a child spend hours examining a bug under a magnifying glass? Why do adults lose track of time reading about topics that fascinate them? The answer lies in one of the brain's most remarkable features: curiosity. Far from being a mere personality trait, curiosity is a sophisticated neurological phenomenon that profoundly shapes how we learn, remember, and interact with the world.

Recent neuroscience research has revealed that curiosity is not just the desire to know, it's a fundamental biological drive that activates the same reward circuits in the brain as food, money and other primary rewards. Understanding how curiosity works at the neural level offers powerful insights for education, cognitive health, and personal development.

The Brain's Curiosity Network: Mapping Wonder

When we experience curiosity, multiple brain regions spring into coordinated action, creating what neuroscientists call the curiosity network. This intricate system involves several key players working in concert.

The Reward System: Curiosity's Engine

At the heart of curiosity lies the brain's reward circuit, particularly the nucleus accumbens and the ventral tegmental area. Research has shown that curiosity triggers the same dopaminergic response in these areas as extrinsic rewards like food or money. When we encounter something novel or mysterious, these reward centers activate, releasing dopamine, a neurotransmitter that generates pleasure and motivates further exploration.

This discovery fundamentally changed how scientists understand curiosity. Rather than being a vague psychological concept, curiosity appears to augment internal representations of value, biasing decision-makers toward informative options and actions. In other words, your brain literally treats information as a reward.

The Hippocampus: Where Curiosity Meets Memory

The hippocampus, the brain region crucial for forming new memories, plays a central role in curiosity-driven learning. When learning is motivated by curiosity, there is increased activity in the hippocampus as well as increased interactions between the hippocampus and the dopamine reward circuit.

This connection explains why we remember things better when we're genuinely curious about them. The dopamine released during curiosity creates an optimal brain state for encoding memories. Even more remarkably, this enhanced memory state extends beyond the information we're curious about to include seemingly unrelated information encountered at the same time.

The Prefrontal Cortex: The Curiosity Appraiser

The lateral prefrontal cortex acts as a sophisticated appraisal system, evaluating uncertainty and determining whether to pursue information. This region supports an appraisal process that determines one's actions, whether to inhibit exploration or pursue it, along with the subjective experience and underlying neural mechanisms.

This appraisal function is crucial because not all uncertainty triggers curiosity. Sometimes uncertainty generates anxiety rather than excitement. The prefrontal cortex helps distinguish between productive curiosity and potentially threatening ambiguity.

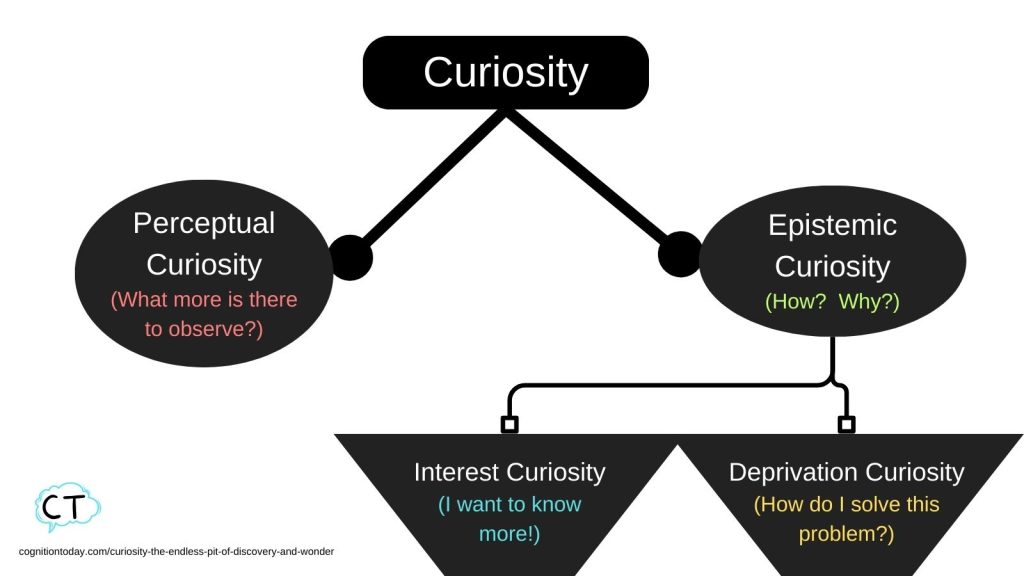

The Two Faces of Curiosity

Neuroscience research has identified distinct types of curiosity, each with unique characteristics and neural signatures.

Perceptual Curiosity: The Drive to Resolve Ambiguity

Perceptual curiosity is regarded as a fundamental drive for information about sensory stimuli, often triggered by stimuli that are ambiguous or novel. This is the curiosity you feel when you see something unclear and want to know what it is, like trying to identify a distant object or figure out what a muffled sound might be.

Recent research at Columbia University's Zuckerman Institute used specially designed images called “texforms”, distorted pictures that could represent either animals or objects, to study perceptual curiosity. Visual areas provide multivariate representations of uncertainty, which are read out by higher-order structures to generate signals of confidence and, ultimately, curiosity.

The study revealed that brain areas assess the degree of uncertainty in visually ambiguous situations, transforming complex patterns of neural activity into a simple signal about how confident you should feel. When confidence is low, curiosity emerges to motivate information-seeking.

Epistemic Curiosity: The Quest for Knowledge

Epistemic curiosity refers to the desire to acquire new knowledge and understanding of complex concepts. This is the curiosity that drives you to read books, attend lectures, or explore ideas deeply. It's the form most relevant to traditional education and intellectual growth.

Research using trivia questions has shown that epistemic curiosity activates similar brain regions as perceptual curiosity, but the motivational dynamics differ. The anticipation of gaining knowledge, the gap between knowing and not knowing—creates a particularly powerful drive.

The Dopamine Connection: Why Curiosity Feels Good

Dopamine is often called the "feel-good" neurotransmitter, but its role is more nuanced than simple pleasure. In the context of curiosity, dopamine serves multiple functions that make it the neurochemical centerpiece of learning.

Dopamine as a Learning Signal

When we're curious, dopamine doesn't just make us feel good—it actually changes how our brain processes and stores information. Activity in the midbrain and hippocampus, along with functional connectivity between these regions, supports curiosity-driven memory benefits for incidental material.

This means that the dopamine surge accompanying curiosity creates a window of enhanced learning. During this window, your brain is primed to form lasting memories not just about what you're curious about, but about everything you experience.

The Anticipatory Power of Curiosity

One of the most fascinating discoveries is that the memory benefits of curiosity depend on anticipatory brain activity—what happens before you receive the answer. Activity in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area prior to the encoding event accounts for more than half of the behavioral variance in incidental encoding during high curiosity states.

This finding has profound implications. It suggests that the very state of wondering—the experience of not yet knowing—is what creates the optimal brain conditions for learning. The journey toward knowledge, not just its acquisition, matters neurologically.

Information as Reward

Perhaps the most revolutionary insight from curiosity neuroscience is that information functions similarly to primary rewards. The same dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain that signal the expected amount of primary extrinsic rewards also signal the expectation of information.

This "information-as-reward" hypothesis explains why we're sometimes willing to endure discomfort, pay money, or invest significant time just to satisfy our curiosity. From the brain's perspective, gaining information is as valuable as obtaining food or other survival-related rewards.

The Curiosity-Memory Enhancement Effect

One of the most practical discoveries in curiosity neuroscience is how powerfully it enhances memory—and not just memory for the information we're curious about.

The Spillover Effect

In landmark research, scientists had participants rate their curiosity about trivia questions. During a delay before receiving answers, they showed participants pictures of faces unrelated to the trivia. Once curiosity was aroused, participants showed better learning of entirely unrelated information that they encountered but were not necessarily curious about.

This "spillover effect" means that curiosity creates a generalized state of enhanced learning. When you're curious about something, your brain becomes better at encoding all information, not just what you're specifically interested in. This finding has obvious implications for education: sparking curiosity about one topic can improve learning across the board.

Long-Term Memory Benefits

The memory advantages conferred by curiosity aren't fleeting. Research has demonstrated that curiosity-enhanced memories persist over time, with participants showing improved recall even a week after the initial learning experience. Dopamine released in the hippocampus during curiosity-driven states can enhance long-term potentiation in the hippocampus, the process associated with memory formation.

This durability suggests that curiosity doesn't just help you cram information temporarily—it helps build lasting knowledge structures that remain accessible over time.

The PACE Framework: Understanding Curiosity's Cycle

To integrate the various findings about curiosity, researchers have proposed the PACE framework: Prediction, Appraisal, Curiosity, and Exploration. This model provides a comprehensive view of how curiosity unfolds in the brain.

Prediction Errors Trigger Curiosity

Prediction errors and information gaps trigger an appraisal process supported by the lateral prefrontal cortex that determines one's actions along with its subjective experience and underlying neural mechanisms. When reality doesn't match your expectations, when you encounter something novel or ambiguous, your brain detects a prediction error.

These prediction errors are crucial because they signal that your current mental models are incomplete. The brain interprets this as an opportunity for learning, potentially triggering curiosity.

Appraisal Determines the Response

Not every prediction error leads to curiosity. The appraisal stage determines whether you'll experience curiosity (with its associated dopaminergic activation) or anxiety (with amygdalar activation instead). Factors influencing this appraisal include:

- The magnitude of uncertainty

- Your perceived ability to resolve the uncertainty

- The potential relevance of the information

- The context and your current mental state

Exploration and Learning

When curiosity is sparked, it enhances learning through increased attentional processes during information-seeking and enhanced memory consolidation afterward. A PACE cycle will be completed once uncertainty is resolved and curiosity is satisfied by closure of an information gap.

Interestingly, resolving one curiosity often generates new questions, starting another PACE cycle. This creates the familiar experience of going down "rabbit holes" of learning, where answering one question leads to several more.

Attention, Novelty, and the Curiosity Advantage

Curiosity doesn't just enhance memory—it also powerfully focuses attention, creating a state of heightened awareness that facilitates learning.

Curiosity Sharpens Focus

Studies using eye tracking have shown that states of high compared with low curiosity were associated with participants' anticipatory gaze toward the expected location of the answer. When curious, people literally pay more attention, with their eyes drawn toward sources of information.

This attentional enhancement occurs automatically. You don't have to force yourself to concentrate when you're genuinely curious—your brain naturally allocates cognitive resources toward resolving the curiosity.

The Novelty Bonus

Novel information receives special treatment in the curious brain. Novel information releases dopamine, which increases engagement and makes content more memorable. This explains why surprising facts, unexpected twists, or unusual perspectives capture our attention so effectively.

The novelty response evolved to help organisms identify and learn about potentially important changes in their environment. In modern learning contexts, novelty remains a powerful tool for engaging the curiosity system.

Age, Development and the Curious Brain

Curiosity isn't static across the lifespan. Understanding how it changes with age can help us maintain this vital cognitive function.

Curiosity in Development

Children display intense curiosity, constantly asking questions and exploring their world. This developmental phase corresponds with critical periods of brain plasticity when neural connections are being established at a rapid rate. Curiosity during these periods helps shape the architecture of the developing brain.

Curiosity and Aging

Traditional psychology literature suggested that curiosity declines with age, but recent research challenges this view. Some types of curiosity can actually increase into older adulthood, particularly when people have the knowledge base and time to pursue interests deeply.

However, the brain circuits supporting curiosity—particularly dopaminergic systems—do tend to decline with aging or in neurological conditions. Brain circuits that rely on dopamine tend to decline in function as people get older, or sooner in people with neurological conditions.

This makes understanding curiosity's neural mechanisms particularly important. By knowing how curiosity works, we may develop interventions to maintain cognitive vitality and learning capacity throughout life.

Clinical Implications: When Curiosity Falters

Understanding the neuroscience of curiosity has significant implications for mental health and neurological disorders.

Dopamine-Related Disorders

Conditions that affect dopamine systems, including Parkinson's disease, schizophrenia, and depression—often include reduced curiosity and motivation as symptoms. These disorders can disrupt the reward anticipation and information-seeking behaviors that characterize healthy curiosity.

Research into curiosity mechanisms may lead to new therapeutic approaches. If we can understand exactly how curiosity enhances learning and motivation, we might develop targeted interventions for conditions where these capacities are impaired.

Memory Disorders

The tight connection between curiosity and memory formation suggests potential applications for memory disorders. Understanding the relationship between motivation and memory could stimulate new efforts to improve memory in the healthy elderly and new approaches for treating patients with memory disorders.

Interventions that enhance curiosity might provide a non-pharmacological approach to supporting memory function, potentially complementing existing treatments.

Practical Applications: Harnessing Your Curiosity

The neuroscience of curiosity offers concrete strategies for enhancing learning and personal growth.

For Learners

Create information gaps deliberately. Before diving into a topic, first identify what you already know and what you don't. This explicitly creates the information gap that triggers curiosity. Ask yourself questions before seeking answers.

Leverage the spillover effect. When you need to learn something you find boring, pair it with something that genuinely interests you. Study them in the same session to take advantage of the generalized learning enhancement that curiosity provides.

Embrace the anticipatory state. Don't rush to get answers immediately. Allow yourself to wonder and hypothesize. The anticipatory phase—when you're curious but haven't yet received the answer—is when your brain is optimally primed for learning.

Seek novelty regularly. Novel experiences and information activate dopamine systems and can reignite curiosity. Regularly expose yourself to new ideas, perspectives, and experiences.

For Educators

Start with questions, not answers. Structure lessons to create curiosity before providing information. Present puzzles, paradoxes, or surprising facts that generate genuine questions in students' minds.

Honor incidental learning. Recognize that when students are curious, they're learning more than just the focal content. The spillover effect means curious students absorb information broadly.

Create psychological safety. Since the appraisal process determines whether uncertainty leads to curiosity or anxiety, ensure your classroom environment makes exploration feel safe rather than threatening.

Use autonomy to boost engagement. Allowing students choice in what they learn about activates the brain's reward system independent of the content itself, enhancing motivation and curiosity.

For Lifelong Learning

Cultivate diverse interests. Don't restrict yourself to narrow expertise. Broad curiosity creates multiple opportunities for the information-seeking and dopamine-reward cycles that keep your brain engaged.

Follow curiosity chains. When one answer leads to new questions, follow them. These curiosity chains create sustained engagement and deep learning.

Maintain novelty in routine activities. Even familiar tasks can be approached with fresh eyes. Asking "why" and "what if" questions about everyday experiences can reactivate curiosity systems.

The Future of Curiosity Research

Neuroscience continues to reveal new insights about this fundamental cognitive function. Recent advances include:

Advanced Neuroimaging

Research employing fMRI while participants rated their confidence in identifying distorted images and their curiosity to see the clear image represents increasingly sophisticated approaches to studying curiosity in real-time.

New imaging techniques may soon allow researchers to observe the precise temporal dynamics of how curiosity emerges and influences learning at the millisecond scale.

Artificial Intelligence Applications

Understanding human curiosity could revolutionize artificial intelligence. Findings on the neural mechanisms of curiosity-based learning might be critical approaches to stimulate independent, curiosity-guided learning in artificial systems.

Machine learning systems that incorporate curiosity-like mechanisms—seeking information to reduce uncertainty—could become more adaptive and efficient learners.

Educational Neuroscience

The translation of laboratory findings to real classrooms remains a frontier. Researchers are working to develop evidence-based teaching methods that harness curiosity's power in practical educational settings.

Personalized Learning

As we better understand individual differences in curiosity—why some people are more curious about certain topics, or why curiosity varies with context, we may develop personalized approaches to education and skill development.

The Deeper Significance of Curiosity

Beyond its practical benefits for learning and memory, curiosity represents something profound about human nature. It's the drive that led our ancestors to explore beyond the next hill, to experiment with new tools, and to pass knowledge across generations.

Curiosity as Exploration Drive

From an evolutionary perspective, curiosity motivates exploration beyond immediate survival needs. What distinguishes human curiosity is that it drives us to explore much more broadly than other animals, and often just because we want to find things out, not because we are seeking a material reward or survival benefit.

This intrinsic motivation to know—independent of external rewards—is uniquely powerful in humans and underlies much of our creativity and innovation.

The Wisdom of Wonder

In our information-saturated age, maintaining a sense of genuine curiosity—the ability to be surprised, to not-know, to wonder, becomes increasingly valuable. The neuroscience of curiosity reveals that this state of wonder isn't a luxury but a fundamental requirement for optimal brain function.

When we're curious, our brains enter a state where learning becomes effortless, memory formation is enhanced, and attention naturally focuses. This is the brain operating at its best, leveraging millions of years of evolution to acquire and integrate new knowledge.

Cultivating a Curious Mind

The neuroscience of curiosity offers a compelling message: your brain is designed to learn through wonder. The reward circuits that make curiosity feel good, the memory systems that are enhanced during curious states, and the attentional mechanisms that focus on novel information, all of these work together to make curiosity one of the most powerful forces shaping human cognition.

By understanding how curiosity works at the neural level, we gain practical tools for enhancing learning, maintaining cognitive health, and living more engaged lives. Whether you're a student, educator, parent, or lifelong learner, the science suggests a simple prescription: cultivate curiosity, honor it when it arises, and trust that your brain knows how to learn when properly motivated by genuine interest.

The ancient philosophers were right to celebrate curiosity as a virtue, but modern neuroscience has given us something more, a detailed map of how wonder literally changes our brains. In a world that often prioritizes answers over questions, perhaps the greatest wisdom lies in maintaining our capacity to be curious, to embrace uncertainty, and to find joy in the simple act of learning.

After all, curiosity isn't just about acquiring information, it's about experiencing the distinctly human pleasure of an actively engaged, perpetually learning, endlessly fascinating brain.

previous

Elder Voices of the Millennium: William Kentridge

next

The Creative Contract Between Humans and Earth: Restoring Reciprocity with the Living World

Share this

Sara Srifi

Sara is a Software Engineering and Business student with a passion for astronomy, cultural studies, and human-centered storytelling. She explores the quiet intersections between science, identity, and imagination, reflecting on how space, art, and society shape the way we understand ourselves and the world around us. Her writing draws on curiosity and lived experience to bridge disciplines and spark dialogue across cultures.